Hello, my name is Chris and I spectacularly failed a placement test for incoming performance majors at a large public university music program. And so it was remedial “Music Theory A” for me.

Welcome to “Music Theory A.” If you’re in this room, it’s because you really don’t have what it takes to be a professional musician. I strongly suggest you change your major today. For those of you who are in denial or just stubborn, go home and draw 100 treble clefs and come back tomorrow.

The next day:

Day 1 - Keys and Scales.

These 7 notes make a scale in the key of C Major: C D E F G A B

Okay. Also... what?

I was baffled already. Didn't we skip something? What are these things, actually... these "notes"? What's the connection between them and the physical sensations they induce in my body and between my ears? Was I born letting my brain do that to sound... turn it into "notes"?

Anyway, I totally drew my treble clefs, and they looked GOOD.

As I followed the familiar music school curriculum, I always had a suspicious feeling about this "music theory." It looked like a self-referential infinite loop... or like a weird subjective vacuum that didn’t bother referencing even the most basic real-world measurements from math or science. Does music theory really only emerge to analyze music that already exists?

... and yet, I heard over and over that "music is math." Cool, I love math. Is there some connection between my trigonometry class and “dominant seventh chords”? Why were (are?) all these composers (still?) putting pitches into “tone rows.” Does it make their music sound, like, more awesome?

Physics uses math as a tool to answer questions and explain real-world phenomena. I always wished music theory would do the same: answer questions about music using something other than music … preferably the tools of science. I was scared it couldn't.

It took 15+ years as a professional musician before I discovered a parallel path, that helped erase that fear... and this is the beginning of that path: the concepts that re-opened my eyes and inspired me to begin again a little further back than day 1 of Music Theory A.

Day 1 - When the air vibrates... my ear senses sound.

Some vibrations are slow enough for me to hear each one separately.

But if the vibration gets fast enough, it creates the sensation of tone.

Vibrate the air, hear the vibrations, speed them up, hear the tone.

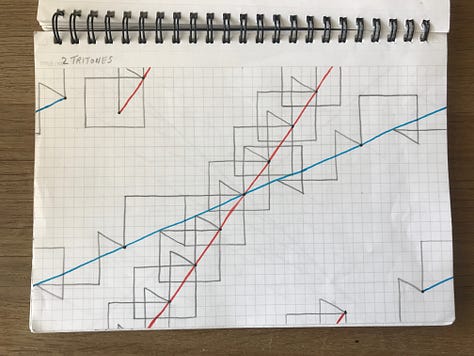

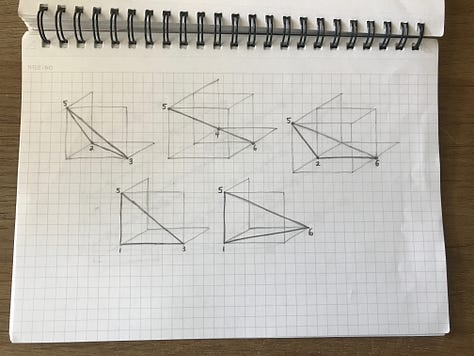

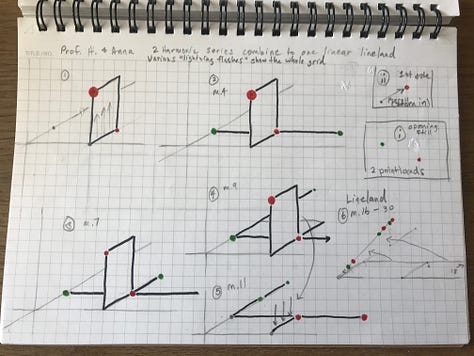

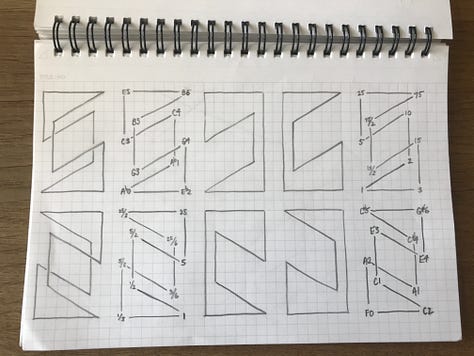

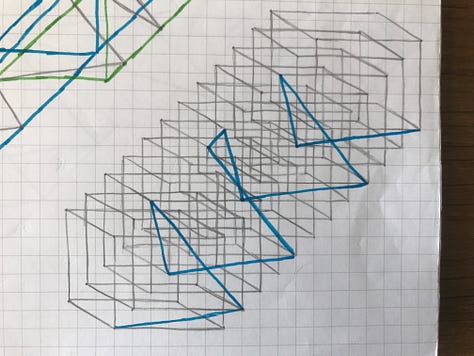

Now that’s a nice place to begin — it starts within the broader context of real-world phenomena. Further down the line: what does it mean, mathematically, to be "in tune"? Can you visualize the relationships between notes geometrically? Would such a visualization help explain our sensation of those relationships?

These are the questions that led me to my own new and mind-blowing realizations and discoveries that were simply not on the menu in my formal music education. I’ve had days that felt like pure magic. I’ve had creative experiences that resulted in work I’m incredibly proud of. And yet there has been crushing loneliness and frustration as well. That’s where the “feelings” come in, and there are a lot of them. I’m also looking forward to discussing the mental health of artists — why we start, what keeps us from stopping, and how we face the pressures of finding our way among all the noise.

🔊 Thank you so much for reading. You can subscribe for free: