Interval Candy

A beginner's introduction to exploring music's lattice - Part II

The best thing I've ever heard anyone say about just intonation is:

… once you learn that interval, it becomes like a certain flavor. I almost think like if you came up with the right methodology for teaching just intonation you could leave all the math out and be like "okay, this is called strawberry.”

This is Kevin McFarland, former cellist of the JACK Quartet, on the podcast Meet the Composer, in 2017.1

I love this quote so much. I love it because it comes from a performer who feels the malleability of intonation in his fingers. He knows the math of tuning, but he also hears it and literally touches it. It makes him a very credible source on the subject — a musician who deeply understands it both intellectually and intuitively. When he says it can accessed from either direction, you can believe him.

"Okay, this is called strawberry"

🍓🔊

So good. Generations of music theory baggage vanishing in thin air, with a smile. For context: he was talking about recognizing and building intervals: specifically the simple ratio-based tunings of just intonation (the quartet then demonstrated how they do this by ear).2

The broader idea that I take from McFarland’s comment is this: we can “leave the math out” because that the math is subconscious. Our brains do those calculations automatically, leaving us with immediate sensation.

The math is always there if we want to explore it, and it’s all the more beautiful when we see that it directly relates to sensations we’re already familiar with.

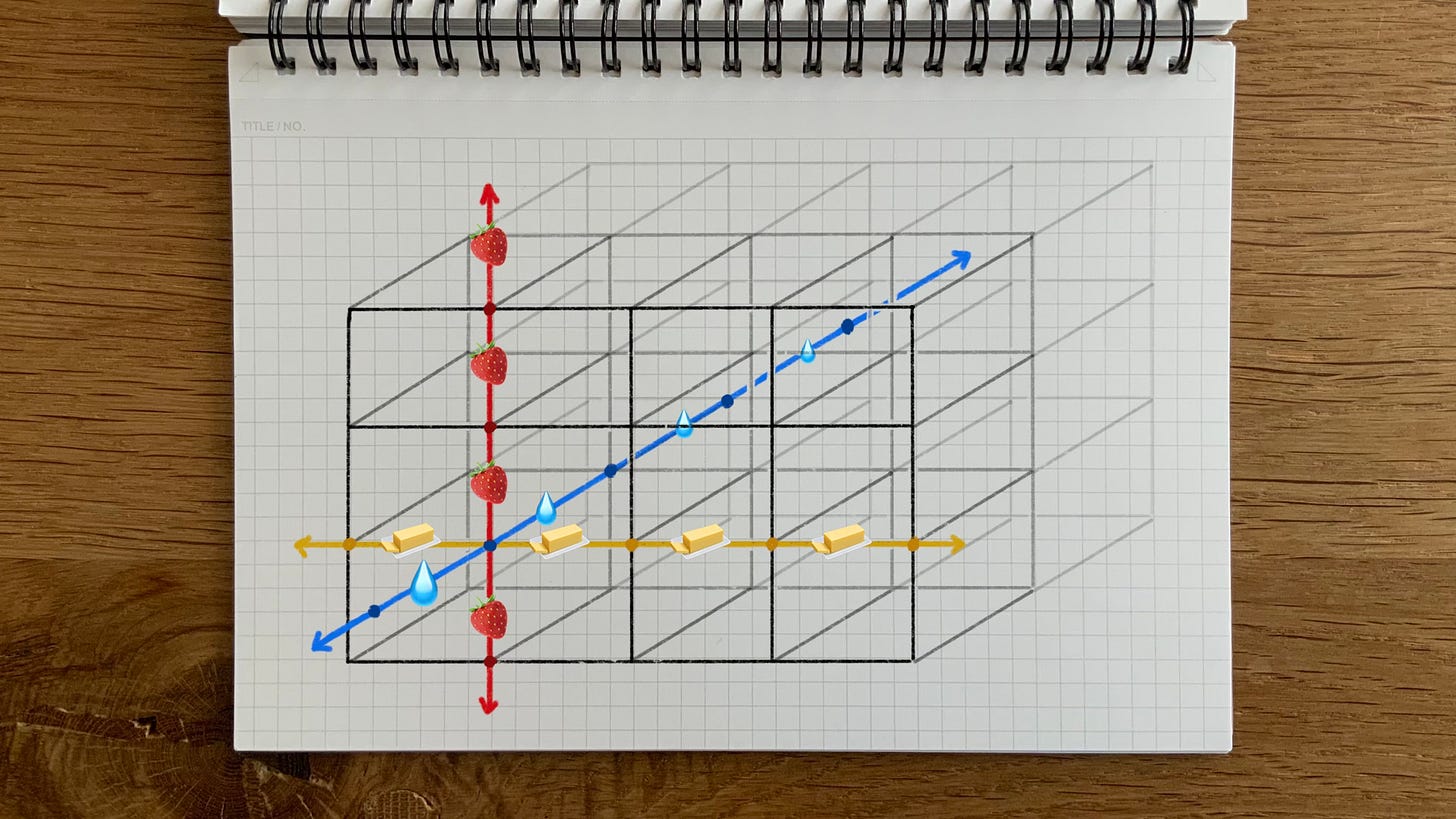

So… recognizing and building intervals also happens to be the next step in our exploration of the musical lattice. The ratios that describe interval flavors are the line segments that are created when you start connecting points:

The taste of primes

This is just a metaphor, and it’s not even a perfect one — it’s just for fun.

I'm not suggesting any kind of connection between sound and our sense of taste, and I’m certainly not suggesting that music theory officially replace interval names with emoji fruits.

That said…

I wonder which interval would be strawberry?

Maybe? Just a suggestion!

So… that ratio: where does it come from?

Shopping for intervals

This being just intonation, we pull intervals off the harmonic series.

If intervals are flavors, the harmonic series is the infinite supermarket. No matter what justly-tuned recipe you’ve planned, you’ll find the the ratios you need to do your cooking somewhere in there.

And as we explore shelves full of intervals, we’ll gradually notice that they build the harmonic series piece-by-piece.

In the above example, I’ve identified my idea of “strawberry” as the distance between the 4th and 5th partials. That’s the 5:4 ratio — an interval flavor containing a mildly concentrated sweetness of mid-level complexity.

But perhaps we could start with something a little simpler… neutral, even?

Water

Factors of 2 - the flavor of no flavor

Ah, octaves: the water of intervals. Not really their own flavor, per se, more like a neutral ingredient that concentrates or dilutes something else. Multiplying or dividing an interval’s ratio by a factor of two is like putting the water in or taking it out.3

Fat

Factors of 3

We’re working up a “ladder of primes” here. Prime numbers are like the flavor profile of intervals. If a ratio has the taste of several prime numbers in its factorization, we’ll intuitively perceive that as a certain type of complexity… or (and this is important for the concept of lattice construction) the quality of being multi-dimensional. When we visualize the lattice, each prime number gets its own dimension.

So if you’ve never been good at wine, maybe interval tasting could be your thing? “I’m getting a strong seventh partial with notes of five and a lot of eleven in the nose.”

The next prime number after two is three. Multiplying or dividing factors of three into a ratio… kind of like adding the fat?

Sauté it in good 3:2, then spread on some unsalted 4:3? Add a little clotted 9:8 to the sauce for richness?

Fun?

There are lots more flavors we can squeeze out of two and three. Infinite, in fact. But we continue up the ladder.

The next prime number tastes are five and seven, and I’ll call those sweetness and sourness. But before I go any further with my wonky metaphor and amateur home cooking, I want to introduce the Michelin-starred chef of interval candy, who also just happens to be one of my favorite internet mysteries ever:

Anonymous interval curation: who is mannfishh??

He first appeared on Twitter under the username “@mannfishh,” with the handle “man fish,” and bio “interval curator.”4 No website, no name, no links to bandcamp or sp9tify… just a stream of short videos featuring delicious and shockingly fresh sounding demonstrations of justly-tuned intervals, visualized — like a music theory class underwater… in black light.

He also occasionally retweeted fish and aquarium related content, and seemed like a genuinely nice person. This would be confirmed later!

Let me just say that I enjoy making musical visualizations very much. I like to think I’ve come a long way with my little animated scribbles and emoji; my goal is always to help make music theory generally accessible to adventurous listeners — and hopefully make my writing a little more interesting, too.

But in the world of just intonation content, it’s mannfishh’s internet. I’m just visiting.

The internet’s baddest microtonalist.

For a while, the Twitter account was all I could find. I just had to know who this is. Then for a while… even that disappeared. I thought he was gone forever. I’m having trouble recreating a timeline for this, I only know that he reappeared around 2021 with a little more profile: still anonymous, but now with a YouTube channel!5 You could finally go through his whole catalog sequentially.

And you absolutely should, because it’s breathtaking.

These videos are pedagogical, yes… but once initial idea is presented, mannfishh rarely bothers to wait around for it to sink in. More often than not the video rapidly explodes into an original composition of awe-inspiring complexity.

For example, this one time I was gonna make a video about the commonly-heard notion of how in just intonation the “circle of fifths” is actually a spiral, and then I found this video and realized yeah… mannfishh has that one covered 😳 :

So there’s that!

The majority of his videos (especially early on), were vertical explorations of the flavors you could extract from the sound of a single ratio. This is why I’m enthusiastically recommending his work now, in the context of this post — when it comes to “interval candy,” mannfishh is like Willy Wonka:

Apparently the 9th partial is his forever and always favorite. I agree, it’s real nice.

So… who is mannfishh? I’m assuming he identifies as a composer, because almost every one of these videos contain original compositions, and he demonstrates masterful facility with notation (including the dozens of extended accidentals used in the Helmholtz-Ellis system of notation).

But is he a composer who writes music for people? Is this the alter-ego of someone we might otherwise recognize? Is he nice?

I don’t have an answer yet. But I do have two clues:

First — from just a couple weeks back. There I was, browsing the Xenharmonic Alliance Discord, as one does. There are a lot of strong opinions in that space. It can be very tempting to dive into the #general or #xen-talk channel and show everyone how smart you are. mannfishh would certainly be treated as a celebrity expert there.

But I’ve never seen him in the clubhouse — rather, he was hanging out in #beginner-help, mild-mannerly answering basic questions from noobies and and encouraging less experienced musicians to explore. A friendly, ego-free fishh. Awesome.

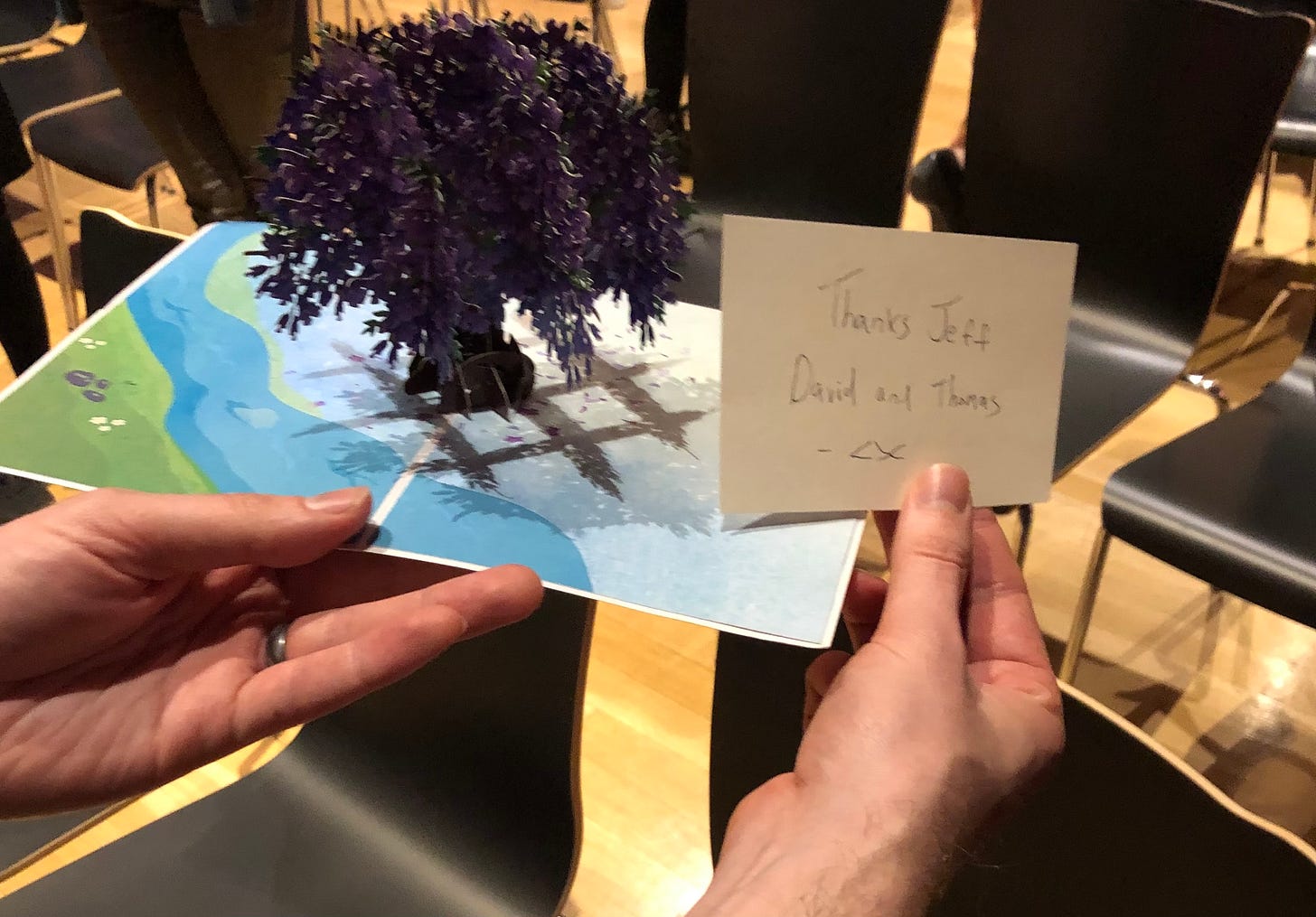

Second — I have a report of his music showing up on a concert for live performers, and I was happy to find that it confirms the kindness in his anonymity. Pianist David Friend recounts:

In October of 2023, Jeff Gavett organized a concert of music for voice and microtonal keyboards with myself and Thomas Feng playing keys. It centered around some songs by Ivan Wyschnegradsky for baritone and 2 pianos, tuned a quarter tone apart.

To flesh out the program, Jeff commissioned some new works, including a piece by Mannfishh. In their interactions leading up to the concert Jeff and Mannfishh only engaged via email, and we were all pretty unclear as to whether or not they would show up to the concert. After we played the Mannfishh piece on the program, we did the typical 'gesture to the composer in the audience' thing, although it was a bit surreal because we didn't actually know if they were in the hall or not. No one stood up, so we sort of figured that they chose not to come -- a little strange, but otherwise uneventful.

The concert went well, and afterwards we were chatting with various people who came (including a not insignificant number of Mannfishh super fans!), as you do. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw something that looked like a small sculpture sitting on one of the (now empty) chairs in the audience. I walked over to check it out, at which point I realized that it was actually a really elaborate pop-up style card, which also included a very sweet note from Mannfishh for us performers. To my knowledge, none of us still have any idea which audience member Mannfishh was or what they look like, although afterwards they did confirm with Jeff via email that they did come to the show and really liked the performance.

Composer as Zorro! Long live the legend Mannfishh!

🥰

Back to our exploration of interval flavors:

Sweet, Sour

Factors of 5 and 7

As we gradually introduce higher and higher primes into our flavor profile, you might notice that all the lower ones are still in play. This is the concept of a “prime limit” — it just explains how far up the ladder of primes you reach. Calling music “seven limit” just means that it limits itself to 2, 3, 5, and 7 (but not 11, 13, or anything higher) in it’s flavor profile.

Umami, Bitter

Factors of 11 and 13

This is where things start to get weird! These primes can blend into other flavors and give them a brighter, fuller timbre. That’s if you use them sparingly. You can also pour MSG on to a block of cheese and chase it with straight angostura bitters on ice.

Some people like that dogfish head 120 minute IPA which is basically like drinking aspirin. Those people might enjoy a factor of thirteen.

This is as far as most people need to go to find all the flavors they need. But you can keep climbing the ladder forever. In fact, they’re still continuously searching for new primes. Currently the largest one has forty one million twenty four thousand three hundred and twenty digits.

Is that a good place to stop? I’m gonna stop there

Proceed to Part III, “A Child in Flatland”

A ride through three dimensions of the lattice, and the Sesame Street / Philip Glass collab that launched a thousand minimalists.

🔉👋 Subscribe for free:

March 7, 2017 - Episode: Bonus Track - JACK Quartet Performs Haas’ String Quartet No. 9. https://www.npr.org/podcasts/528124256/meet-the-composer

The JACKs went on to demonstrate building a chord in two different ways: first justly-tuned, and then equal-tempered. Host Nadia Sirota makes an interesting observation: building the first chord happened way faster.

You would think the “standard” tuning of equal temperament would be quicker, easier. But with the justly-tuned chord, the ratios are ingrained in our intuition. When they’re right, it’s crystal clear, and that can happen very fast. Tuning an equal tempered chord involves much more guesswork, and is therefore takes longer. Go figure.

(hear this whole sequence at 6:45 into the episode linked above)

As we explore interval flavors we'll multiply and divide by two feely and ad nauseam, all over the place. It’s good to know this is happening — and that they call it "octave equivalence.” Although I’m not a fan of the term. There’s nothing inherently “oct” about 2:1 intervals — they are factors of two. Couldn’t we call them duples?

I have assumed he/him applies to “mannfish” for obvious reasons. But mannfish is anonymous and has never clarified any pronouns as far as I'm aware!

https://www.youtube.com/@mannfishh/videos

I had to think of a citation attributed to different mathematicians and philosophers, I quote the version of Manjul Bhargava: “There is great complexity in simple things, if you look for it. And there is great simplicity in that complexity.” I think that your work shows this beautifully, Chris.

Mind-blowing stuff, Chris.

Overwhelming, incredibly informative and exciting!

More!!!