Hoooo boy, IT’S HOT, and today we’re gonna dissect a licensed and certified summer banger. Let’s get SWEATY:

This track just hits so hard right out of the gate. It had me at :02. I’ve never purchased something so fast on Bandcamp. I think I paid my £7.49 GBP before I had even made it 8 bars. But what was it that unlocked my consumer impulse so quickly?

Explosive contrasts in energy — created through the effective use of musical ratios. (duh!)

This is Take Me To Your Sky (by Fourth Kind, as included in 2020’s Breaking The Beats: A personal selection of West London sounds), and the ratio in question is:

4 : 3

I spent many hours spent scouring bandcamp for obscure bops to “spin” in my covid-era zoom dance parties. The tracks that effectively used 4:3 always hit hardest. Let’s get into it.

Quick refresher… why do I bother with ratios?

… because humans have a miraculous ability to sense ratios on three scales of perception: pitch👂, tempo🫀, and phrase 🌬️ — without ever needing to be taught to do so. 1

… because they are the truest, simplest, most fundamental unit of analysis for making sense of what music does to us.

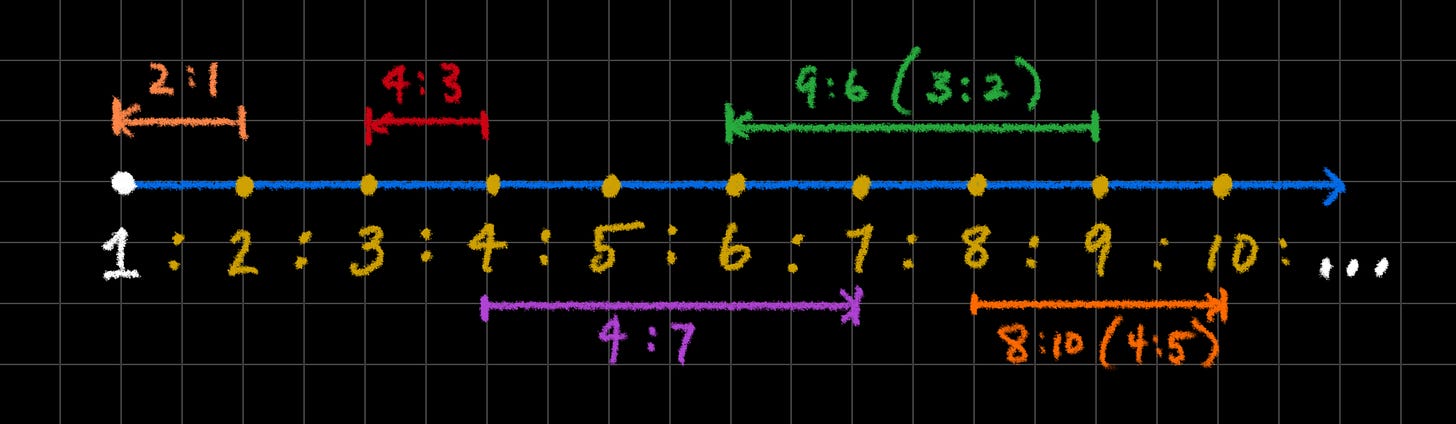

… because the harmonic series is a construction of every whole-number ratio, in order! It is a comprehensive encyclopedia of possibilities: pick any two partials… you have just named the ratio between them.

👂 Here’s what 4:3 sounds like:

🫀 Here’s what 4:3 feels like:

🧮 Here’s what 4:3 maths like:

The name of this ratio is 4:3.

But you can call it… 4:3.2

👇 The ghost below the surface

The tempo implications of Take Me To Your Sky can be mapped to a simple harmonic sequence with a fundamental (aka “1st partial”) tempo of 42 beats per minute.

In this track we never directly experience that fundamental tempo (in red above) — and this is not uncommon: in a churning sea of rhythm and tempo relationships, the fundamental is often like a ghost, hiding deep below the layers of faster vibrations that rise to the surface.

Rather, we spend most of the track experiencing the push-and-pull between the 2nd, 3rd and 4th partials of this tempo series:

2nd : 3rd : 4th

84 bpm : 126 bpm : 168 bpm

💸 Intro: six beats in, and I’ve already bought the record

Those first few beats of the intro are so electrifying. They charge forward at 168 bpm🏃♂️, and then the hi-hat pulls it back to 126 bpm🚶♀️. This cycle repeats. That’s our 4:3 relationship. There’s a tension and ambiguity in this push/pull… which tempo will we stick with?

After doing this fourth (ahem… back and forth) three times, the tempo briefly, ecstatically opens up: with a couple big expansive beats at 84 bpm. That’s the “2” in what we now realize is a 2 : 3 : 4 relationship.

That 2nd partial tempo feels broad and voluminous — like looking up to the wide open sky. Then… a huge pause, like an exhale.

👨👨👧 A family of tempos

Once this track gets going, the drums lock in at 126 bpm. This tempo is our center — the “3” in our 2 : 3 : 4 relationship:

It’s a good mid-range sustainable tempo for dance music. A club DJ would have a whole section in the crate for music at 126. Think Earth Wind & Fire’s September. Or Souza’s The Washington Post. Or… save time! Think of them together:

126 is lovely and clean mathematically: it can be divided evenly into 2, 3, or 7 parts. Elegant! We like that.

And indeed if we were to divide it by 3, we get a nice whole number — 42, which happens to be our aforementioned “1” — the fundamental.3

Meanwhile, the piano is alternating between 168 and 84 bpm.

168 bpm can really burn: think the breathless pace of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.” I tend to think of 168 as the upper practical limit of dance music.

On the other hand, 84 is walking tempo. A huge contrast. And yet, it has an incredibly strong bond to 168. It is half as fast. They are in a 2:1 relationship.

I recently wrote about how tempos in a 2:1 relationship have such a high degree of “sameness” that you experience them as one. That’s what’s happening here with the piano: you can hear that 168 bpm and 84 bpm are hugely different levels of forward energy, and yet alternating between them doesn’t feel like a real tempo change because they have so much sameness.

Like tempos in octaves.

🫴 The push and pull

Within a strictly metronomic tempo of dance music, it can be a challenge for a DJ to find ways to make the music breathe — expand and contract, push and pull. Too much fluctuation messes with the flow.

The beauty of the 2:3:4 relationship between energy levels in this track is that they can all be layered on top of each other without it ever taking more than 3 or 4 beats to line up again. These are simple juxtapositions that anyone can feel while simultaneously moving at a constant tempo.

The same couldn’t be said of tempos not in simple, whole-number ratios. They just wouldn’t work the same way. The tempos would diverge, rub against each other in dissonance. Dare I say… they would be “out of tune.”

This is why 4:3 shows up so frequently in dance — it’s one of the simplest relationships for related tempos, such that they both lie within the useful bpm range of dance music.

So as the drums stay consistent, the piano keeps tugging at them from both sides: sometimes we feel 168 in the piano, sometimes 84. There are beats of 126 in between as we wait for downbeats. It’s a constant cycle of fast, medium, and slow:

But the tempo never actually changes.

👂 There’s another 4:3 hiding in there

Here’s a little zoom in on the last two chords of that piano line:

What we have here are also 4:3 relationships. Same ratio, different scale of perception — we experience them as pitches. We might call them “G over D” and “F over C.” But the ratios between them are the same… they are both four over three.

This is the point I want to make again and again… music theory typically does not speak about tempo and pitch using the same terminology. Because they trigger different modes of perception, we assume they are two unrelated musical elements that need different tools of analysis.

It isn’t true. The ratio between “G” (392 beats per second) and “D” (294 beats per second is 4:3. So is the ratio between 168 beats per minute and 126 beats per minute. All pitches are just really fast tempos. All tempos are just really slow pitches. There’s a grey zone of perception in the transition between — but that doesn’t mean we can’t speak about both on the same terms.

Back in that intro — the exact moment the tempo moves in a 4:3 ratio is the same moment that the chords move by a 4:3 ratio. The track goes from a sprint to a jog, from a flame thrower to a campfire, from 4th gear to 3rd — on two different levels of musical cognition at once. It feels so satisfying and natural and … harmonic. 🧬🙂

Now, a demonstration of everything described above…

⛅️ Many more clouds in the sky

Take Me To Your Sky is just one track in a sea of dance music that makes use of the 4:3 ratio.

I will admit I spent most of my life trying to avoid situations where I might be expected to dance: I didn’t get it. Why.

…but all that ended in 2020 when I discovered this hyper-prolific little trio of Dutch bop-makers known as Kraak & Smaak. The undisputed champions of four against three:

I simply couldn’t stand still any longer.

A couple other fun examples:

Music Sounds Better With You, by the secret Daft Punk Side-Project “Stardust” uses 4:3 in an almost identical manner as the intro to Take Me To Your Sky:

… as does the classic Commodores track Machine Gun (I won’t link to the Boogie Nights clip but I’m sure you remember it):

Finally, some gorgeously subtle incorporations of 4:3 all over one of the most surefire party hits of all time:

Subscribe for free:

I talked about the miraculous ability to perceive and reproduce ratios at extremely high speeds in this previous post. In a nutshell, the fact that Kelly can make her vocal chords vibrate at exactly 392 times per second, without even hearing the individual vibrations, is Miracle #1. When LaTavia then makes her vocal chords vibrate at exactly half that speed just by “thinking” it… that’s Miracle #2.

The musicians reading this are waiting for me to say it — expecting me to be perfectly forth-coming about what this interval is “called.” A perfectly understandable expectation. But I’m not gonna! I set forth to you: this interval is “4:3.” That name is the Perfect description of what’s happening, mathematically. Fourth partial against third. To call it something else would be to introduce a back and forth between “what it is” and “what we call it.” It wouldn’t be that confusing now, but later it would get real confusing. And I don’t want to dump cultural and historical baggage on it. So, henceforth: 4:3. If you still just really just need to hear it said, say the name of the artist who made this track out-loud.

and yes, I know: also “the answer to life the universe and everything.”

Thanks for the insights and research! I indeed love the 4:3 ratio, actually all the examples you posted. I'm also a big fan the triplet echoes common in reggae/dub music.