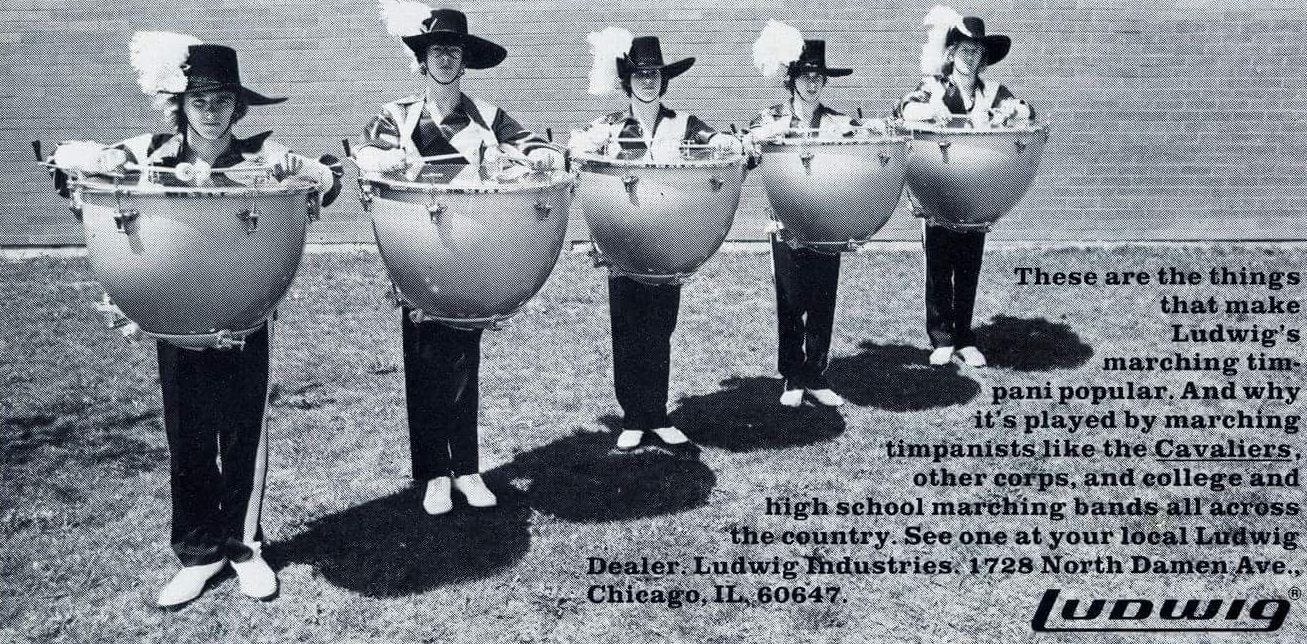

Would you believe me if I told you they used to march the timpani?

Do you have questions? I had questions.

🙋♂️ aren’t those things heavy?

A modern timpano is anywhere between 55-150 lb — these were surely designed to be lighter than that, but it still sends a extra shiver down my already trembling spine. The awkward playing position must have been brutal on the shoulders. I’ve heard there were also marching vibraphones at this time, but that idea is too terrifying to even type into Google.

🙋♂️ isn’t it hard to keep those things in tune?

Timpani have specified pitch. Where other drums are typically just tuned to “drum sound good 🦧” and left to fluctuate with the temperature, humidity, and political climate, timpani play a critical harmonic function in the ensemble: roots and fifths, open triads, bass lines, or even melodic elements. They need to be tuned accurately, and accuracy with tuning doesn't exactly vibe with ten hours of rehearsal in 100% humidity on a 95 degree day in Alabama.

I'm speculating… I wasn’t there — but even on plastic heads, wouldn’t they have been constantly at war with the pitch in the summer heat and direct sunlight? In this documentary about Fred Sanford and the 1978 Santa Clara Vanguard drumline, you can almost hear the blinding glare of the sun off those copper bowls. Just the sound of this clip1 makes me squint my eyes.

🙋♂️ wouldn’t that be easier for one person?

Maybe, but drum corps is a competition and this was the 70s: the rules said everyone marches. And anyway, why play something alone when you could round up a couple friends and split it — have everyone grab a pitch?

Splitting

The challenge in marching timpani was more than just carrying them — it was the singular satisfaction of splitting a single instrumental voice between more than one player. This requires the development of a unique skill with timing and phrasing that feels so unlike anything else in music. It feels like several brains becoming one.

There are a handful of examples of splitting to explore, but the practice of marching timpani is an interesting entry point because it went extinct before it had a chance to really evolve into its own art form. When I think of marching timpani, this simple little tune from the annals of drum corps history is the first thing I hear in my head:

The four timpanists are splitting this charming bass line from the Santa Clara Vanguard's 1976 arrangement of Send in the Clowns (which, over the years, turned into a deeply emotional calling card2 for the corps as a whole).

The second thing that comes to mind is the same corps’ launch into the percussion feature of Benjamin Britten's Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra, a piece that would come back several times over the course of the 70s. For fans of the Santa Clara Vanguard drumline, this is a pavlovian cue to start drooling: when the timpanist(s) play this, you're about to hear piles and piles of notes from the rest of the drumline.

But why?

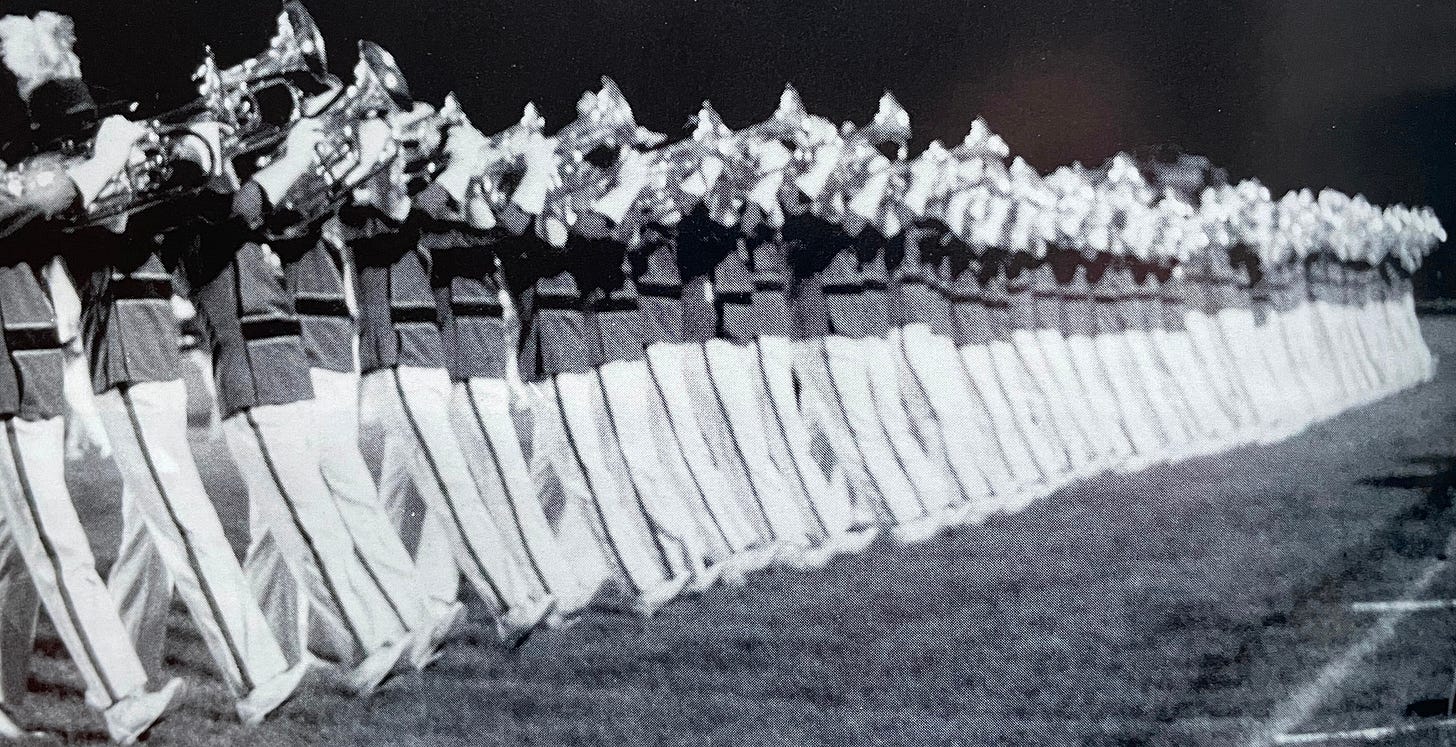

Splitting a timpani part was nearly always more challenging than just letting one person play it. You had four or five times the chance for human error in tuning and timing. But in the drum corps activity, if a musical voice was important enough to be included, it was put on a harness and marched. There even used to be a “starting line” — all instruments were required to start outside the line and march in.

That didn't last much longer. In 1978, the “starting line” rule was phased out and timpani started getting snuck onto the sideline to be played by one musician. This launched what would become the modern “front ensemble” of stationary instruments (aka the "pit," as I hope they still call it).

Here's Young Person’s Guide revisited again eight years later, in 1981 — now played with electrifying style by a solo timpanist:

It’s hard to argue for the split-up marching timpani when you compare it to this. The benefits of a using a single player outweighed the pull to keep every musician on the field as part of the dynamic visual design.

But another section of the drumline was playing music that wouldn't be possible in the hands of a single person. Over there the practice of splitting continued, thrived, and ascended to breathtaking technical and musical heights.

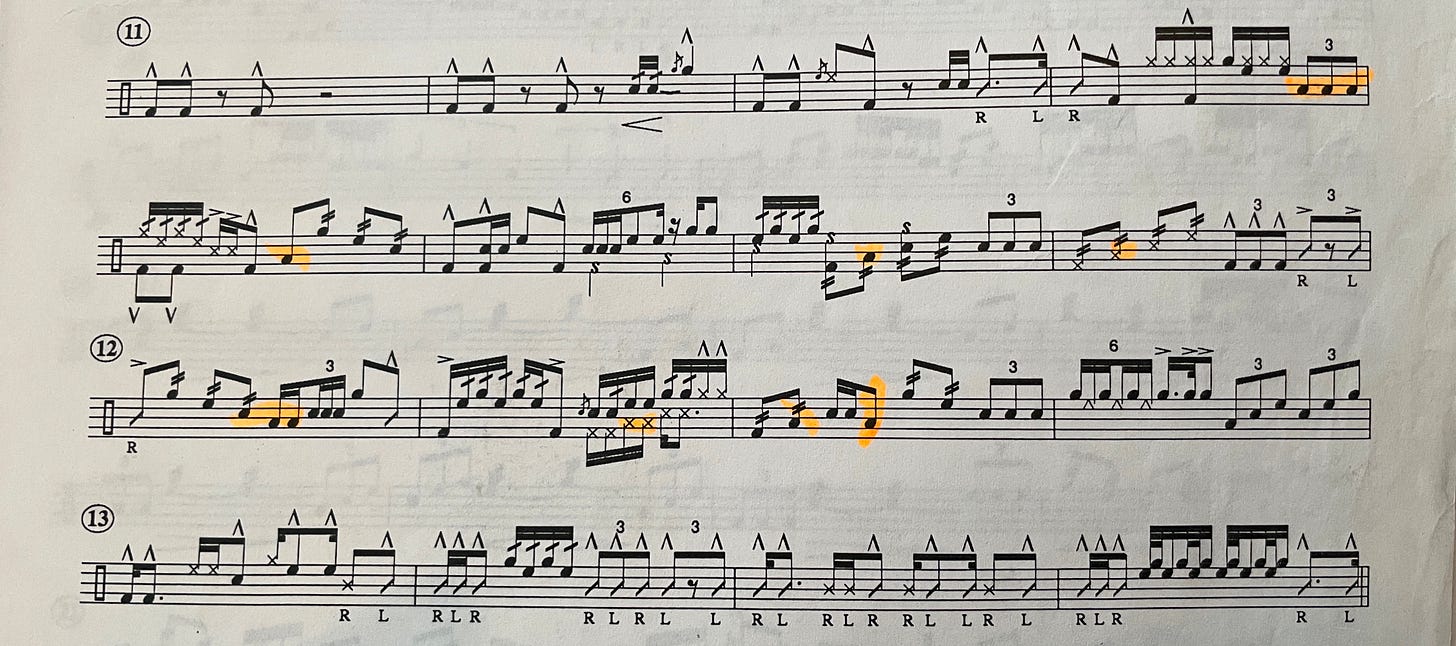

Threading needles - the marching bass drum line

Hooooo boy, here we go. While marching timpani may be extinct, marching bass drums are still out there running around the field today, and the difficulty of what they do continues to evolve. This version of splitting of a single voice between several musicians requires impeccable timing that I believe is unparalleled anywhere else in music. I generally try to avoid this particular type of hyperbole, but I'm ready to stand behind this claim. Look:

The quick attack and short decay of these drums lends itself perfectly to blisteringly fast, agile passages. Even if this were playable by a single person (it isn’t), I’m just not sure it would do anything for me. The power in this music is in the mental focus of five brains dividing the work of one, and I can't think of anything else in any music that requires it — fast, linear material, split up with one player to a pitch. They create one voice. It’s unbelievable.

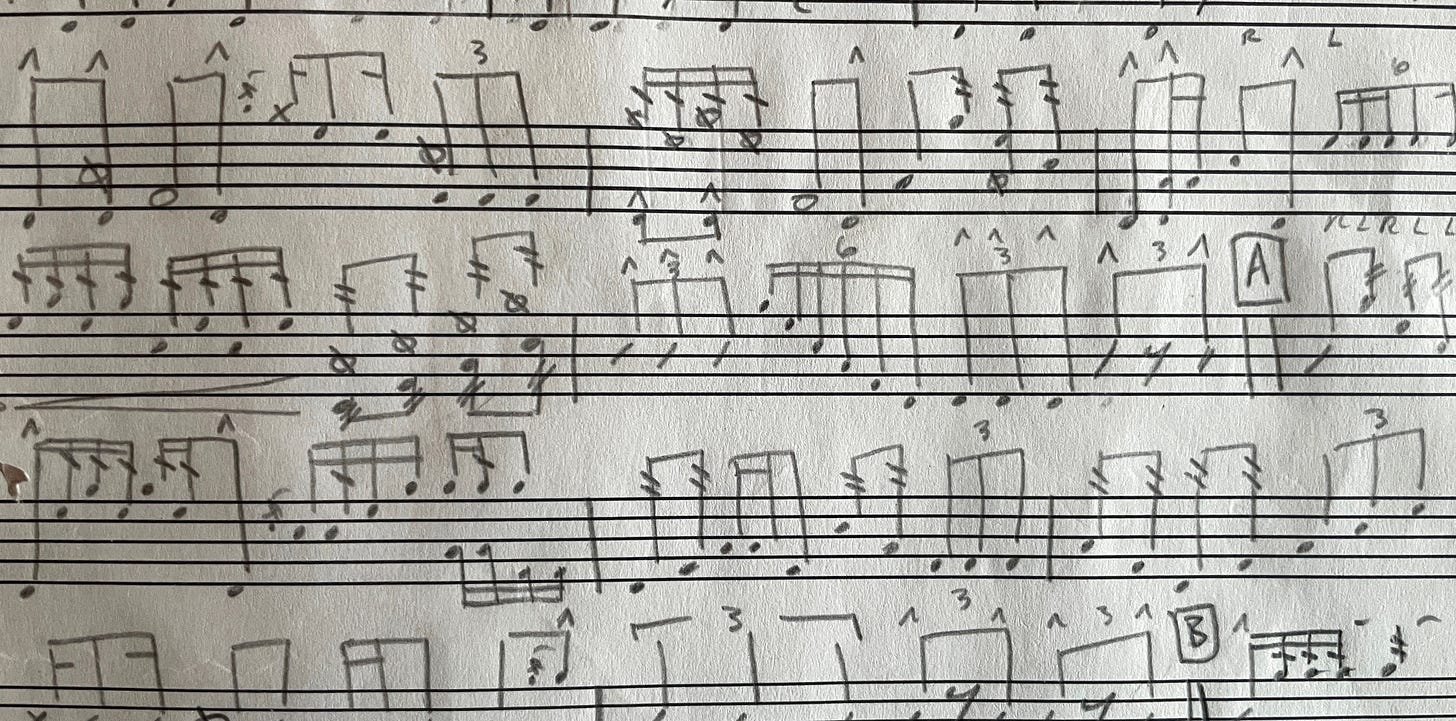

As a young drummer and composer, the marching bass drum line absolutely captivated me. I dreamt of splits. I carried around manuscript paper and wrote marching bass drum parts in my classes.

The way marching bass drums are notated reflects the necessity of composite musical thinking. Each player doesn’t have their own “part.” There is one part, for the entire section. For example, a five-player split might be notated in the spaces of the staff, as if it was a single instrument with five pitches. And it is a single instrument — it’s just performed by five humans.

Today you can easily hear drumline arrangements played back by realistic computer sample libraries. Back then, I had to just imagine it. Eventually my high school drumline friends and I created a bass drum ensemble to try out our compositions. This was my first and only “garage band.”

Ensemble virtuosity

Confession: I’ve never been able to get very excited about a “virtuoso.”

I used to think this was a character flaw: what’s wrong with me? It’s not that I’m not impressed, I’m just… bored. But why? What could possibly be boring about a concerto, or an aria, or a solo improviser? There are technical fireworks! High notes! Cults of personality!

Why has it never done anything for me?

I think it’s because the idea of ensemble virtuosity got to me first. It’s the discipline of surrendering the individual ego to the faceless personality of the ensemble. I know that sounds cultish and possibly even un-American but it’s just what I’m drawn to in music: families, rather than individuals.

Give me Concerto for Orchestra over “Concerto (with orchestra)” any day. Bartok’s beloved 1941 “concerto” has no soloist, instead treating the sections in a soloistic way — tapping the ensemble virtuosity of each.

… and for me, the marching bass drum line is a beautiful expression of that ensemble virtuosity. The players must know exactly how their individual part fits into the whole, but that’s only half the battle — in performance they must be able to think and hear the composite, while only actually playing a fraction of it.

Splitting changes

All of this may bring to mind another musical tradition — this one with five hundred years of fascinating history and performance practice. Change ringing is the art of splitting in possibly its purest form (and an early example of algorithmic composition). The ensemble rings a collection of bells in mathematical sequences, with each player performing only their own bell’s part of the composite line.

Change ringing is mostly associated with giant full-circle bells in towers (do not try to march those things, please). But it’s also performed on handbells, which make it easier for us to see what’s going on. Handbells allow for greater agility, opening the possibility of each player managing two pitches, or even four as the gentleman in the center of this ensemble demonstrates:

I’m just a tourist to change ringing — I don’t speak authoritatively on the subject, but only as a fan.3 In fact, I will admit that I still can’t get my head around it. I live in a world of notated music — learn it from the page, and then memorize. Change ringing is conceptualized algorithmically, and it baffles me. How are they able to think about these patterns so that they can go through every possible permutation (sometimes over the course of several hours), without getting lost?

For a more informed take, I recommend Dom Aversano’s fascinating recent piece on change ringing — he covers not only the mechanics of the patterns, but also the historic and socio-political context:

Splitting Image

Once I aged out of marching percussion and entered the real world4, I really missed splitting. It’s so fun, and it creates a mysteriously intoxicating camaraderie.

I get little tastes of it, especially in certain types of complex contemporary music: a quick figure divided between multiple players, a Klangfarben-style melody, even something like the “motor” parts of Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians. But that all just whets my appetite.

This week, I’ve got splitting on my mind as Alarm Will Sound prepares to perform and record Pale Icons of Night by Oscar Bettison. About twenty five minutes into this piece, there is an extended duo for two percussionists on tubular bells. There are five pitches used: Matt takes the lower two, and I take the upper three — it bears a striking resemblance to the kind of material a marching bass drum section might play (albeit with some very new music-ey time signatures), and my brain immediately shifts into that mode as we do it.

To aid in that mental shift, we combined it into one notated part, and split it.

Coda: no ambition, just vibes

There’s a particular state of deep focus that I’ve experienced in the performance of certain music that involves sustained attention to timing. The composite listening gets so deep that it becomes meditative and I stop registering what’s directly in front of my eyes.

In drum corps, we used to call it the “vibe.” And this young change-ringer’s got it:

Subscribe for free:

Sources for all the videos in this post:

Santa Clara Vanguard drumline rare footage with Fred Sanford 1978

Not Santa Clara Vanguard 1976

1973 Santa Clara Vanguard

Not Santa Clara Vanguard 1981

2018 DCI Finals Lot: SCV Bass

SCV 2022 Drumline | In the Lot | SCV Bassline - DCI Finals Week

Handbell change ringing - Simon Melen rings four bells to Bristol Maximus

Henry’s handbell focus

Watch Gail Royer, the corps founder and director of 25 years, conduct "Clowns" for the last time: after finals in 1992, just months before we lost him: https://history.scvanguard.org/scv-clownsafterfinals-1992/

Anyone want to start a garage band of change ringers???

However one might define the “real world,” the drum corps activity (especially pre-smartphone) is the opposite. Drum corps is on another planet… another galaxy. It’s awesome.

This is one of the best music posts I've encountered on Substack. Fascinating and timeless. Drum Corps barely crossed my radar before reading your posts - I didn't think it could be so interesting or relevant.

Thanks for the mention of my post. In terms of campanology, I used to play full peals on the drum kit to get an embodied sense of them. 'One person splitting', if you don't mind a total contradiction. I've never had that group experience though.

That is just fascinating watching that archival footage. Loved the whole post!