This article is an homage to the first item on the syllabus for a class I will probably never teach: a survey of how I became… whatever it is I am.

Today’s “textbook” isn’t about music, but has been so foundational to my own sense of what it means for anyone to be an artist, writer, composer, etc… that I have to begin with it. It is unquestionably the most important book on my shelf.

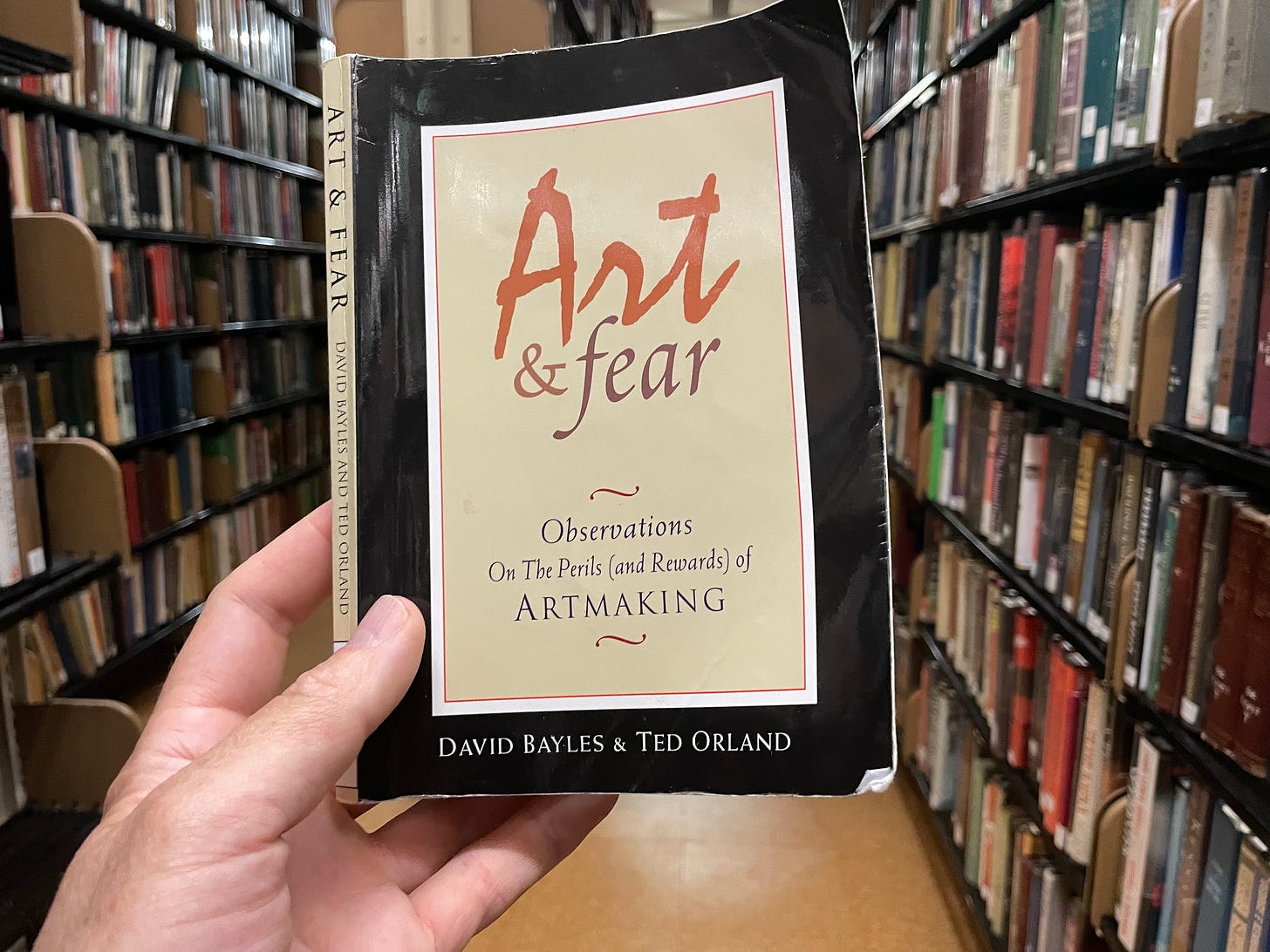

Twice each year my calendar reminds me to re-read Art & Fear by the artists David Bayles and Ted Orland. I’m not sure there’s any piece of media in my life with more repeat visits. Its authors created this book over a 7-year collaborative process, writing in parallel during years of discussions on a couple simple questions:

How does art get done?

Why, often, does it not get done?

And what is the nature of the difficulties that stop so many who start?

In internet parlance of 2024, those questions aren’t the most effective click-bait imaginable. No “engagement” for you, David Bayles & Ted Orland.

And yet. There’s just something about this book. It’s only about 100 pages — you can read it in a sitting. Alternatively, you can read a single paragraph and spend a sitting’s length of time thinking about that paragraph. As a book, it is a masterpiece of straightforward, crystal clear writing. It is just so concise — there is not one unnecessary word, and it gets straight to the point and stays there.

I find I can open up to any page and ingest a week’s worth of creative sustenance within 45 seconds. That’s the same time it takes a YouTuber to:

explain why they haven’t posted a video in so long (sorry guys!) and

introduce you to their sponsor.

This book is not trying to be literature, and yet it features some of my favorite sentences ever written. Pick one, quote it out of context, and it will be useful and thought-provoking and true.

Here, I’ll do one:

Virtually all artists spend some of their time (and some artists spend virtually all of their time) producing work that no one else much cares about.

Ouch. Did you see that? It was my bratty self-important internal child being sent to his room. A devastating thought — and yet obliquely helpful? I feel like I’ve simultaneously been punished and given permission to misbehave. Note: this isn’t a quote I’ve saved with a highlighter on a dog-eared page. I literally opened the book just now and pointed at a random sentence.

I’ve gifted this book to so, so many people (in fact, DM me and I’ll gift you a copy right now, and we can be friends 😀). I can’t even remember how I originally discovered it… I don’t think I’ve ever heard it mentioned in any context anywhere.

… and certainly not recently. Do you follow the latest trends in self-optimization? This book is from 1993. Are you drawn in by beautiful book design and minimalist aesthetic? The cover and typography are so dated they border on criminal. Do you always make sure to stay up on the wisdom of today’s most influential creative thinkers? Bayles & Orland quietly go about their own work (they are both excellent photographers). They have basically zero public persona. Neither has a “brand.”1 If either even has a website, I can’t find it.

The way I would describe this book, in a word: refreshing. It’s not selling you anything, other than maybe itself (for way less than it’s worth). Your local library probably has a copy (please go to your local library).

Assumptions

Bayles and Orland explore questions about art-making that are useful and universal across any discipline — and they don’t just ask these questions, they take a stance. Their assumptions, observations, and conclusions are difficult to argue with: they are logical and level-headed. They are, I think, relatable for anyone who might make art.

Three stated assumptions:

Artmaking involves skills that can be learned.

To speak from my own experience: when I committed to composing music full-time, I quickly discovered that I did not yet have most of the skills I needed to do my own work. I assumed this would result in failure. But, to my delight, the skills I needed could, and would, be learned. And now I confidently stare down the skills I have yet to learn, for the work I have yet to do.

Sounds obvious. But I was surprised how often my brain gave me an idea and then immediately sabotaged it. “… But you don’t have the skills necessary,” it said. This is true… I couldn’t have all the skills necessary to make that particular work until I’ve made it.

Art is made by ordinary people.

Whether or not there is art made by extraordinary people is beside the point. If, like me, you proudly count yourself as an ordinary person — the authors argue that art is made by ordinary people like me and you. “All art not made by Mozart,” as they put it. I just find that reassuring.

And yet I spent half my life trying to be extraordinary. External feedback often made it through. One of the most freeing realizations I ever had was that although this feedback is interesting, tempting (addictive?) — it’s ultimately none of my business.

What I am: an ordinary human being with an entire mixed bag of personal strengths and weaknesses that are my own. The authors argue that as an ordinary person, if I can embrace both, I will use both to do my work.

Making art and viewing art are different at their core.

My own journey to accepting this point led me to identify two personal traps:

“I see the finished work in my head… then I make that finished work.”

“I love (or hate) someone else’s work… then I make work like it (or not like it).”

The latter point is far more obviously a trap — judgement of someone else’s finished work can only be made in reference to my own. And by focusing on what’s already finished, I have inherently pressed the pause button on my process: I won’t be making anything.

Trickier is the former point, which involves trying to view the finished work living in my own imagination. Isn’t this the first step in making it? Unfortunately not… I would sit down with whole album concepts in my head. I would feel so inspired and excited for my future self… and get absolutely nowhere. This went on for years. The space between that moment and the finished work was an ocean. I could barely even dip a toe in before giving up.

As a starting point, viewing art never led to making anything. Viewing art is about responding to a finished artwork, and I discovered that making art, by definition, can only be about responding to the process.

One day I sat down thinking “I love a justly-tuned major 10th so much” and suddenly it was a year later and looked around as if waking up from a dream — a different person, with a new set of skills, and a finished album (never before viewed by me or anyone else) in my hands.

The Fear

I made so much music from age 12 to 19. I filled manuscript books full of pieces for imaginary drumlines. I turned a dual-cassette boom box into a multi-track tape deck, playing along with one side as I recorded to the other (the speed over the tape head was slow — every added overdub pitch-shifted the whole project up a half step — and this barely registered as a problem with me).

Without access to any kind of synths, samplers, or hardware (I wouldn’t have known what those things were anyway), I scoured the pre-internet Bulletin Board Systems of the (408) and the (415) with my 2400 baud modem looking for any software that might allow me to make tracks. It was the 90s and downloading took hours. It has recently surfaced that one piece of software I discovered then (and never heard of since) was being used at the exact same moment by my hero and icon Aphex Twin. (I always knew we had identical creative journeys… we’re like, basically the same person.)

I clip here a little excerpt from some of that juvenilia (never before on the internet!)

I shared this track with a composer friend a few years later:

“Wow, everything is so up in your face… there’s like, no reverb at all.” - him

“What’s reverb” - me

The massive gulf between my skills and my creativity hadn’t bubbled into my consciousness yet. It didn’t matter.

And then I went to music school. Here came the fear. This was the first time I ever stopped.

How to Not Quit

A central concern of Art & Fear is how to not quit. And quitting is different from stopping. Those are their words. I’ll let them explain:

Artists quit when they convince themselves that their next effort is already doomed to fail.

And artists quit when they lose the destination for their work — for the place their work belongs.

Quitting is fundamentally different from stopping. The latter happens all the time. Quitting happens once. Quitting means not starting again — and art is all about starting again.

I’ve stopped so many times. I’ve fantasized about what it might be like to relieve myself of this burden and do something completely different. I’ve made myself so busy being a vehicle for other people’s work that I’ve effectively procrastinated my own for months, even years. More frequently, I’ve come to a stopping point, become so overwhelmed with the idea of starting again, and convinced myself I have run out of ideas completely (no, let’s be honest — I convinced myself I never really had any to begin with).

Just a few examples of my life as a serial stopper:

Finished an album… gotta spend 6 months not making anything while I deal with putting it out.

An email has come in.

Wow, I’m productive. I’m going go to take a walk outside and think about how totally awesome and prolific I am. For the rest of the day.

Wow, I’m worthless. I have nothing to say. Even if I did, nobody cares. Making anything would be pointless. I’m going to go to the park and stare at the ground. For the rest of the day.

Refer to audio:

Sad Will (my algorithmically-generated brain-voice) is ready to stop.

All of these are stopping, but none of these are quitting (thank GOD). And becoming consciously aware of the difference was transformative: I could allow these periods of stopping to happen, and let them take as much time as needed to pass. I could breathe again.

Artists who continue and artists who quit share an immense field of common emotional ground. (Viewed from the outside, in fact, they’re indistinguishable.)

As disappointing and unsettling as it is to watch myself stop over and over again, I can always know I haven’t yet quit, and there’s no inherent difference in the emotional world of those who do one or the other. And through accepting this, I have, so far, always managed to begin again.

There are approximately 8 million writers out there claiming to know how you, the aspiring (or struggling) artist, can follow through with your goals and produce the art you’ve been dreaming of producing. Yes, Rick Rubin has entered the chat, as have all the influencer-guru experts. They’ve got advice for you, along with a link to The Help You Need (sponsored post).

Yup, by writing this article, I guess I’m doing the same thing. I recommend getting a paper copy of Art & Fear. It costs $12.04 and weighs like 3 oz… I like to carry mine around. It’s a nice way to spend some time away from this screen you’re staring at right now:

Appendix — caring for an artist

There’s so much more I can share from my own personal experience with this book, and I probably will in bits and pieces over time in other articles. But there is one question I want to ask, that the book doesn’t seem to touch:

How can a person who loves or cares for an artist help their art get done, and reassure them that stopping isn’t the same as quitting?

I’m very fortunate to have a husband who already possesses a “smiling buddha”-like mastery of responding to my artistic struggles with empathy, kindness, space, and acceptance. I try to do the same in return. To me, his ability to navigate in and around my emotional world is borderline miraculous… because being a friend, or partner, or family member of an artist is a mine field.

When the work is going well we ask you what you think, and hope you’ll know the right thing to say. When the work isn’t going well we arrive to you limping, distant, silent, irritable — and hope you won’t take it personally. We hope you’ll somehow know how to not make it worse. We are desperate to be understood, even though we know better than to expect it. We hope you can help, but hope you won’t “try to help.”

For me, part of accepting my own work was about learning how to best respond to the other artists in my life. It was a lot of trial and error. I’ve found Art & Fear to be a helpful resource in that sense. Consider mentioning it to your best friend, your partner, and maybe your shrink. I believe it could be useful to everyone.

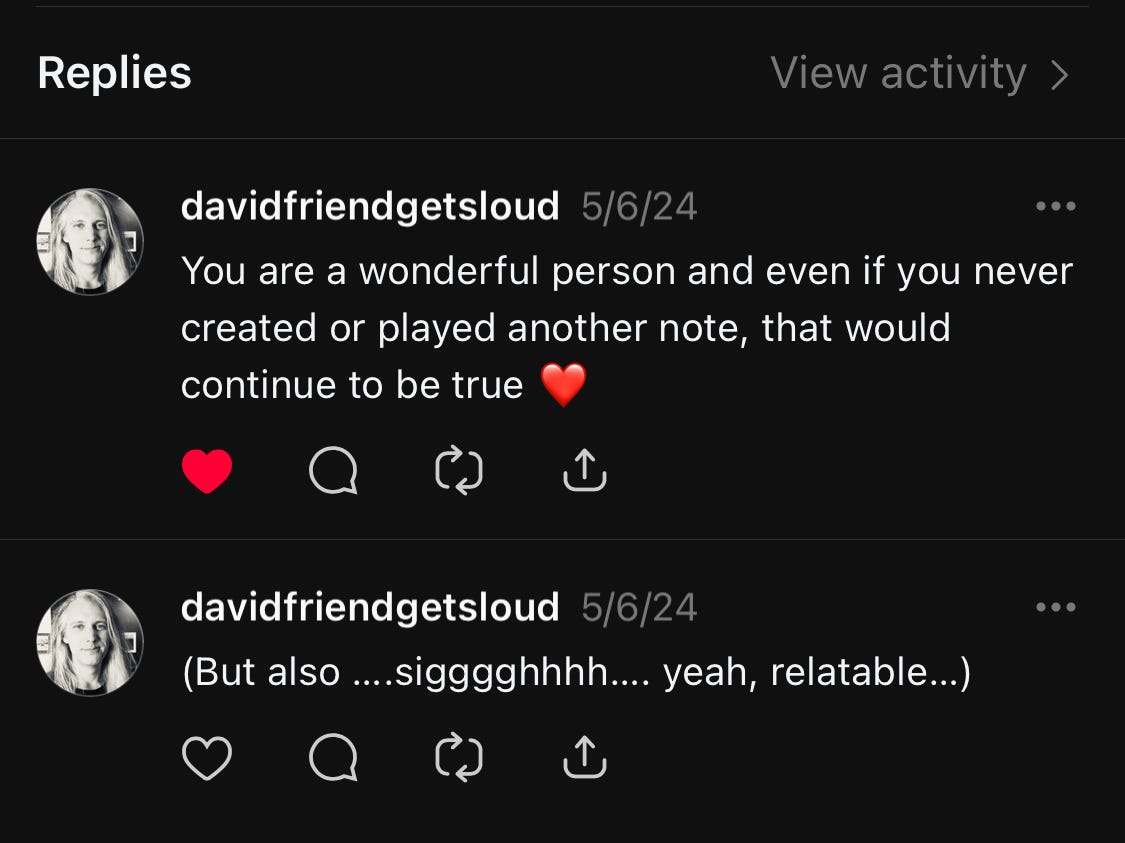

I’d love to catalog how, specifically, we can emotionally support an artist we care about. I have lots of thoughts about that for a future article (and would love to hear yours). But in the meantime, just be like David Friend:

Subscribe for free:

As a person with a common name who has now fully publicly committed to a middle initial “P.” as in “Paul,” I’ve never related so much to this disclaimer from the website of photographer David Paul Bayles:

“I share a name, a profession, a state and a friendship with David Bayles, the photographer, writer and co-author of Art and Fear. In the many weird ways the internet can mangle and merge information, we have sometimes been presented as one human, and I assure you we are not. I am David Paul Bayles and he is David Bayles. We live forty miles apart in the state of Oregon. And I highly recommend Art and Fear.”

Great article. Very relatable. Love the track. I also found my teenage years to be unabashedly prolific (and some of that stuff still feels ok to me decades later). I’m definitely going to check out the book. Cheers!

Wow. I love this so much and can't believe I have to wait a whole week for your next article. In the meantime, I'm going to get myself a copy of Art & Fear and make a note on my calendar to re-read it at least once a year. Thank you Chris P. Thompson.