The Way We Tune Now - #3

Hot intonation and a spot of dirt with Center Snare Guy & Friends

Previously, on The Way We Tune Now, an uncomfortable question for any drummer:

Am I “unpitched?”

Wondering where everyone’s at with this? I’ve landed on “no.”

After exploring Helmholtz and Solomon, simple tones from boom-boom cars, the grey area between modes of perception, waveforms set to “stun,” a stomp on the floor, and one very dubious world-record claim… I look in the mirror today, and I believe:

I have pitch.

I always did (and I always will). But, well… one existential crisis just leads to another:

Does that mean I “tune?”

↕️↔️🔀 The Way We Tune Now is open-ended series of inquiries into pitch and intonation through the unconventional lens of a drummer and percussionist. These aren’t meant to be textbook-y or to even really “teach” anything — I’m just telling stories about some connections I made that blew my mind… long after any conventional music education.

Today I’m sharing one of my all time favorite videos on the internet1, and asking: does a drummer ever get to experience the sensation of tuning a pitch in real-time?

Huggadugga burr

Like many percussionists, I was a drummer first. And for the first five years of my music education, the only "in tune" or "out of tune" I knew sounded like this:

What am I looking at here?

Nine drummers, warming up for the show. They are half-dressed but not yet behind the drums, so we’re probably catching a candid moment before the more official parking lot warm-up. “We warm-up before the warm-up” is such an exquisitely typical drum corps sentiment — they are warming up now, and they likely warmed up together on the bus ride over from an all-day rehearsal (after which they were already very, very warm). They likely haven’t been “cold” since like 9:30 am.

What is this music?

I hope that in 2011 they weren’t still calling it what we called it in 1992: “huggadugga burr.” That ridiculous name predates creative ensemble drumline exercises with titles like “Martian Mambo” and “Poof,” and harkens back to a simpler, more literal time: “huggadugga burr” is just onomatopoeia for what it sounds like when you play four single strokes followed by four double strokes.2

Is this a rhythm?

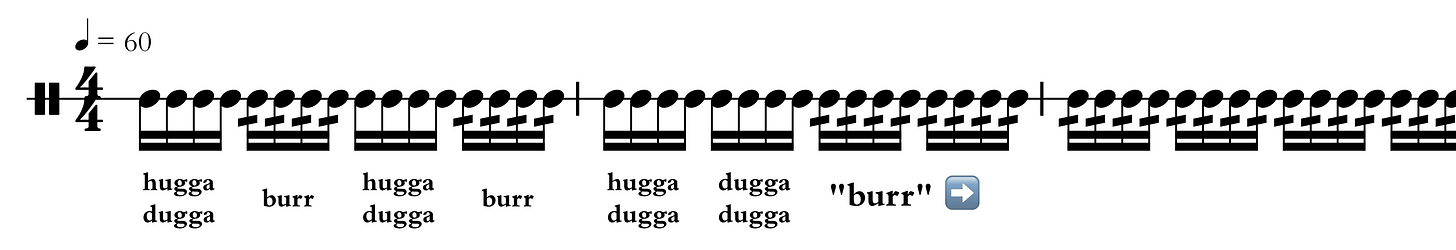

Yes of course. Here it is expressed in the notational system of 19th century western European classical music:

Is this a pitch?

Well now that’s a loaded question… I’ve accepted as my truth that a stomp on the floor, (and similarly, a single strike on a fence), does have pitch.

But this music… this continuous stream of pulses created by drumsticks, particularly the “burr” part — at a frequency of 16 Hz… is this a single “pitch,” and if so can it be tuned?

My personal answer to the former is yes, and this footnote 👉 3 will explain my reasoning, but for now — let’s just say it doesn’t matter! Whether you call it rhythm, pitch, or just “the burr part,” the experience of getting it in unison with eight other performers doesn’t feel at all like a rhythmic exercise. It feels like an intonation exercise.

These drummers are tuning.

What I talk about when I talk about dirt

Marching percussion and its broader drum & bugle corps activity are judged art forms. Yeah that’s right, I’ll say it again: music is a competition, and the goal is to win.

The adjudication methods for this dubious task have evolved steadily over about fifty years, seemingly in an attempt to make the act of judging musical performance less… dubious. The judges sheet used to be a “tick” system… start with an assumed perfect score and tick every error, highest score standing wins (mmm… dubious).

Today the judging has evolved into a “build up” system, ostensibly to better account for difficulty of the show design — still with dubious effect on the activity, just in new and different ways!4

But long after the tick system disappeared (c. 1984), the term stuck: a “tick” is just a momentary lapse in visual or musical synchronization. As a drummer I’ve always thought of a tick as a single rhythmic error.

A stream of ticks? We called that “dirt.”

I call your attention back to eighteen seconds into today’s video for a spot of dirt, and the consequences:

Rookie, you can't hide from Center Snare Guy.

Center Snare Guy hears everything.

This particular footage is something really extraordinary in a sea of internet drum corps content. Because these drummers are “off-stage,” we get glimpses of their reactions (or non-reactions) to what’s happening in real-time, and the hierarchy of leadership shows through immediately: Center Snare Guy5 commands this unit and is the judge of what’s acceptable. Several other drummers are clearly empowered to react when something isn’t right, while others are absorbed fully in their own personal struggle.

End Snare Guy stands paralyzed like he just ran into a grizzly bear who hasn’t noticed he exists yet.

The history of drum corps facial expressions is… dubious… deeply performative, borderline cringe.6 But in this moment, there’s no performance. We’re seeing the labor of the pure physicality of music-making on each individual face. Nine unique styles of flow state, locked together in a trance that is stronger than the sum of its parts.

There is an ecstasy in this sensation, and I remember it vividly — the experience of creating a continuous stream of pulses, while practicing a type of deep listening into the surrounding unison that fills my whole body with that frequency (rhythm? pitch?). An incredible sensation.

The squeaking pop of every single stroke being amplified by a perfect alignment of air pressure — it felt like magic then, and it still does today. But after thinking about tuning and pitch in my post-drum corps life, it was a mind-blowing moment of integration when I looked back and realized — I now see this as an exercise in intonation.

When intonation is bad, it’s said to be “out of tune.” But again — we didn't know anything about that. We just called it “dirt.” And I’m happy to see that they still do today:

In the world of marching percussion, the opposite of dirty is “clean.” And apart from the briefest lapse of intonation, this snare line is very, very clean.

And that’s how you win at music — warm up for the warm up, police the intonation, and be as clean as possible at all times.

👆Also very very clean: the 2018 Santa Clara Vanguard (and they won!)

Subscribe for free.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/@drumndenverr

“huggadugga” — four pulses, four syllables. Rhythm?

“burr”— eight pulses, one syllable. Pitch? 😲

If “pitch” is defined as a perceptual property that makes it possible to judge a simple tone as “higher vs lower” (rather than “faster vs slower”) — then the answer to “is 16 Hz a pitch” is just barely:

A simple tone at this frequency is just within the potential range of human hearing. It could be labeled “C0",” also known as "an octave below the lowest C on the piano." Four octaves higher (aka four times faster), that same simple tone would be crystal clear. We would call it middle C.

But — all that applies to a simple tone only. A strike of a fence (and any other naturally occurring sound) is complex (comprised of many simple tones of different higher frequencies). A complex tone at 16 Hz is much more clearly audible, and lives in a grey-area between our perception of individual pulses and our sensation of continuous tone. Here’s what 16 Hz sounds like played by a synthesizer set to a complex tone:

I made that recording by holding down the low C on my midi keyboard. That’s right, I could play along with this snare line… with one finger!

I’m mostly joking. Drum corps wouldn’t be half as awesome if they didn’t compete. It’s a necessary evil.

I’m obviously just having fun and projecting my own fan-fiction with all of this — I don’t know anybody from this particular group (were you in it? bang my line). In fact, from what I can gather this snare line was actually full of rookies to SCV, including the center snare?! If true, that would be extremely rare. Can anyone help me fact-check this?

EDIT: information continues to come in. “Center Snare Guy” in my estimation was actually one-off center, and the actual center is obscured behind him in this video. Also, apparently this exercise was something they did quite a bit on various resonant surfaces.

Again, I love it. Drum corps wouldn’t be what it is if it was anything else. “We are cringe, but we are free.”

You may be interested in Etienne Nillesen's work with tuning snare drums. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yOuSOHx0lOc