Are you tired of all the arguments?

Does it seem like these days it's always just "who's rushing," or "who's dragging?"

Are you starting to question your own sense of time… of reality, even? Do you refuse to believe we live in a post-truth world? Maybe you wish you were making more of an impact… actually helping people? Or do you dream of escaping “onto the grid” — to a more organized universe?

Do you get a tingly feeling when you watch “Tron?”

Have you ever considered a career in click-tracking?

On June 7th, 2007 I buzzed into the old Ayers rehearsal space on 47th street in midtown Manhattan for a rehearsal with Alarm Will Sound. Ayers was old-school NYC freelance musician stuff: housed in a beat-up Hell's Kitchen row house, it was simultaneously an affordable rehearsal space and percussion rental company, which killed two birds with one stone and made it a favorite of the lively DIY contemporary music scene. It was also breathtakingly impractical. The rooms were strange irregular polygons — spaces impossible to fully make use of. It had all the modern professional amenities of a late 19th century tenement. A tiny little elevator in the center of the building could barely fit three humans with their instruments, and shuttled disassembled percussion gear between floors one piece at a time. I always wondered how they got pianos in and out.

It was only my second or third time playing with this “Alarm Will Sound,” and when I walked into the "big" room I gasped at the chaos. Not only was this space way too small for a sixteen-piece conducted ensemble and its infamous kitchen sink percussion setups, but today every inch of the floor was also covered in tangled headphone extender cables.

Are you detail-oriented, technology-friendly, and able to work under pressure? Is your greatest weakness that you're "a bit of a perfectionist?"

Follow in the footsteps of the greats: the composer who lined up a hundred metronomes, or the nerd who created a paradigm shifting tempo map. Make order from chaos, and make it your career.

Ordered chaos

On the menu for rehearsal: Benedict Mason's Animals and the Origins of the Dance. I had a vague idea from working on my part that there might be a click track involved in some capacity, but this was the point I realized that there wasn't one — there were fifteen. Every member of the ensemble had their own individual tempo map, synced in the computer and fed to in-ear monitors.

As the ensemble started to sloppily squeeze into the room and I pondered the sliding tile puzzle of percussion needs, trumpet player Jason was alternately hunched over a laptop and running around trying to confirm that the outputs were going to the correct chairs.

Remember that Nine Inch Nails video? It looked exactly like that:

😌🤘I knew immediately I had found my people. But also: from that day on, I couldn’t stop thinking about all the possibilities… of all those click tracks.

As a click-tracker, you'll be on the cutting-edge of musical discovery, and thus be in a position to improve lives. You know that Radiohead song everyone thinks is soooo crazy? You can be the person who says "yeah, it's actually just in 4/4."

Just imagine: you might be the person in your band who discovers a genius new way to bar the measures, simplifying the time for everyone. You might be the one who finally brings us all together.

Polytempists I’ve known

I had already played some music with more than one tempo juxtaposed simultaneously. It's tricky to make it work, usually requiring that the ratio between the two tempos be really simple, and hopefully that it not be held for very long.1

But… multiple tempos synced via in-ear click tracks? Now we’re cooking with gas. Before I encountered Mason's Animals, this thought had never even occurred to me! You could make magic happen with this idea.

Musicians could juxtapose material at any number of different tempos precisely. Careful crafting of the musical material contained within those tempos could create fascinating and unexpected rhythmic interactions.

You might just start to think of tempos and pitches on the same terms.

The relationship between two tempos becomes an "interval.” Juxtapose three or more tempos at once? It’s beginning to look a lot like a "chord." One simple example might be to layer 60, 75, and 90 bpm. That’s a ratio of 4 : 5 : 6.

What do we call a chord made of tempos? This one could be, quite simply… a major triad.

Today's click-trackers are in high demand, solve challenging problems, and work flexible hours. Join a supportive team of professionals full-time, or make it a side-hustle: bill by the project, by the hour, or work pro bono for musicians in need.

The pixels

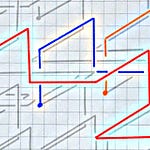

This week's wackier-than-usual music video is a visualization of all the click tracks from Jitterbug Mechanique (the first movement of Animals) played back simultaneously. Pixel art, with it’s visible quantizations of space and playful tone, felt an appropriate medium for a very fun piece with a very angular subatomic structure.

During performance, no one musician would hear this composite. Rather, individual tempos are sent to the players who need them, one at a time. I had to sneak into Alarm Will Sound’s Google Drive after-hours to listen to them all at once, and experience a music no one gets to hear: the hidden music of structure.

Mason's schematic for the tempos in this movement is not as complex as it seems. He divides the ensemble in half. Group one is the winds: flutes, clarinets, and saxophones. Group two is everyone else.

Group one - a chord of tempos

Group one is split into three different simultaneous tempos: 90, 120, and 150 BPM, but always in a common meter (first 2/4, then 3/8 near the end). Their different tempos cause them to sync downbeats only every three, four, or five cycles of their respective tempos. They enter and exit the larger texture of the ensemble as a unified group, always maintaining the same ratio between themselves.

That ratio between the tempos is 3 : 4 : 5. I've visualized this (in pixel art styling) with dice and roman numerals.

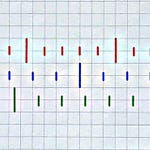

Visualizing tempo precisely in animation can be tricky, depending on frame rate. I made a little cheat-sheet to figure out how many frames were in each rhythmic value, for video that is running at 30 frames per second. Turns out 90 : 120 : 150 is a great tempo relationship for working with mostly round-number groups of frames (with the exception of those pesky 5/16 and 3/8 bars):

Group two - polymetric jitterbug

Group two (brass, percussion, keyboards, strings) maintain a constant tempo of 120 BPM, but have a much more adventurous metric life. Their map of the piece includes various time signature changes, and their musical material further implies other tempos internally. This group dances.

I've visualized their click track with the HAL-style boxes, and the other implied tempos with various pixel art visuals.

Click-trackers live lives of comfort and stability, knowing that even the most self-indulgent rubato can't erase the ground from beneath the feet of society-at-large. You'll have the satisfaction of being the ultimate authority on all things related to time — enjoy twice the credibility of a conductor, without ever waving your arms around like a weirdo!

A career in click-tracking

Although playing Animals (and later recording it) was exciting and wonderful and revelatory for me, it didn't cause me to run home and start composing poly-tempo music… yet. The idea simmered. It became a sort of bucket list idea — something I filed away for later.

That time came when I discovered the ratio-based tuning of Just Intonation, and started making music with it. Could tempos and time signatures be “in Just Intonation” as well?2 How could that idea be realized in live performance? Here was the fascinating application for multiple in-ear click tracks.

Today I am Alarm Will Sound’s in-house click-tracker. This is a job I created for myself, and for which I continue to happily manufacture demand. What a career! Very fulfilling — when I'm making a click track, I'm uncovering the low frequency music underneath the music: the notes, intervals, and even chords, of tempo.

Click-tracking: when music is your job, but tempo is your passion.

Jitterbug Mechanique

All this complex rhythmic material comes together to create one of the most breathtakingly creative and boisterously fun pieces ever. Let’s goooooo!

Animals and the Origins of the Dance

Movement 1: Jitterbug Mechanique

Alarm Will Sound

a/rhythmia — nonesuch records, 2015

Video, art, and animation by Chris P. Thompson

Subscribe for free:

There's a very nerdy new-music conducting practice of showing two tempos at once, one with either hand. Alan can do this perfectly, and I still make life difficult for him — "can you bring your left hand three inches higher and point your right hand more toward the brass section?" (I still get lost).

It can work, but it looks a little like a parlor trick and occupies the same place in my head as playing marimba with six mallets.

I started to think of a tempo as being analogous to the fundamental pitch of a note. A tempo might be 3 Hz, and a pitch might be 300 Hz. The logic follows that rhythmic material played within that 3 Hz tempo might be analogous to the unique waveform, and thus timbre, of the 300 Hz pitch. The more cyclical the rhythms (straight sixteenth notes, for example), the more they function like harmonic partials.