According to the Museum of Obsolete Media, Steel Recording Wire has an Obsolescence Rating of 5/5: Extinct, or very high risk.1

… recordings are made on thin steel or stainless steel wire. It was introduced in 1898 by its inventor, Valdemar Poulsen. As well as being used for dictation purposes, wire recording was also used for home entertainment, for example for recording radio programmes.

Its popularity peaked in the late 1940s and early 1950s.2

On Christmas Day in 1949, in a typical use-case scenario for this format, my grandparents somehow got a hold of a steel wire recorder and spent the day passing it around to everyone gathered at the house and recording bits of music from the radio. It doesn't seem like they actually owned the device, because there are only a couple spools, and they are all from that one day.

Humanity may soon forget what it's like not to have immediate access to the sound of our parents’ and grandparents’ childhoods. I imagine there will be so much recorded and it will be so immediately available that we'll feel like we were there — and be mostly uninterested.

For now, we still worry if the media itself survives and can be transferred. Although now completely obsolete, steel wire is actually quite stable for long-term storage, and the recordings from this one day in 1949 were well-preserved.

Getting digitized recordings from these spools in 2015, over 65 years after they were recorded, felt like magic — specifically, hearing the voice of my then three-year-old mother, and the grandfather I never knew (family name Bortner, everyone just called him “Bort”). Also, the texture of the audio quality is just delicious — if there’s a way to fake this sound with some modern plug-in, I certainly wouldn’t know how to do it.

There was palpable joy in the air of this house, which Bort built for his young family with his own hands upon returning from the war. I was delighted to discover how much of that air was filled with music. Although they did tune into the Messiah being broadcast on the radio (likely why they borrowed the wire recorder in the first place), mostly the music was homemade, the way it used to be done: on an upright piano in the family living room.

My mother gave a little recitation, receiving gentle encouragement.

But perhaps the most musically shocking moment was when my grandfather started… rapping? …or at least, that's what it sounded like to me?

What on earth just happened???

I had to know what this was. Lyric searches led me to the "talking blues" recordings of Woodie Guthrie, as he is most commonly credited with popularizing the form and infusing it with social and political commentary. There is, in fact, a recording from 1947 that could have been where my grandfather learned it:

But further search revealed the real originator of the genre, a "balding, bespectacled, pipe-smoking man from Greenville, South Carolina named Christopher Allen Bouchillon."3 When Bouchillon went to an Atlanta studio in 1926 with his sons to record two songs under the name "The Greenville Trio," the recording director thought his singing voice was so awful that he encouraged Chris to just recite the lyrics while he played. Talking Blues was born, becoming a big hit in the late twenties.

The fact that grandpa's spontaneous version of this song lyrically more closely resembles the earlier Bouchillon version makes me wonder whether he picked it up before Guthrie’s recordings existed… possibly hearing the original 10" Shellac from 1927.

I spent so much time with these wire recordings, and they were endlessly fruitful as sample material for my first two albums — including two pieces of music I've shared today, affectionately named Museum of Obsolete Media I and II.

Such a museum really exists — it has over 800 different media formats covering audio, video, film, and data, and was founded in 2006 by Jason Curtis in the rural county of Shropshire in England.

Get the album:

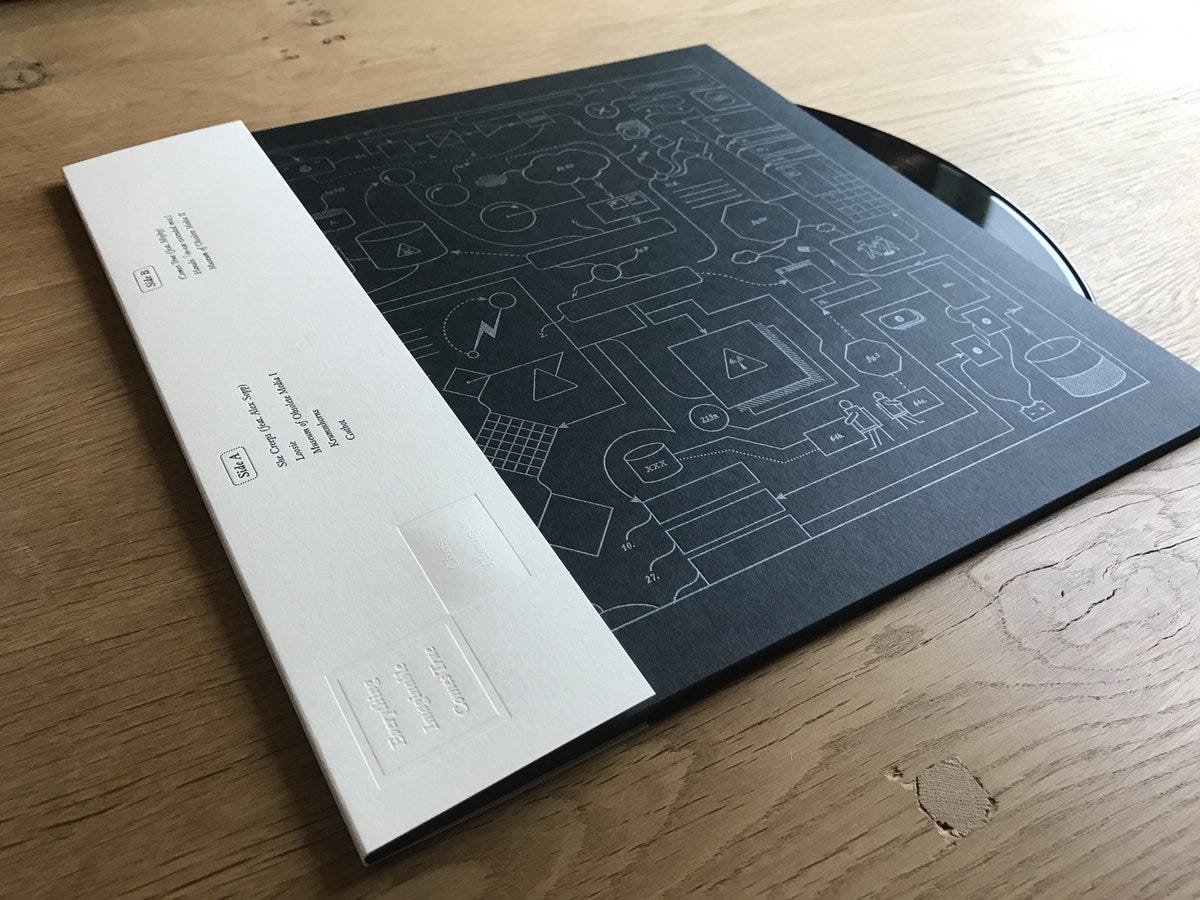

These two tracks come from my 2019 album Everything Imaginable Comes True, which you can listen to here. If you order a copy on vinyl, I’ll slip one out of the devil’s hand and slide right into… a very handsome craft-letterpress embossed package designed by the ingenious Timo Andres:

And mail to you. With a nice note!

Subscribe for free:

Share this post