This week I’m sharing a new study for solo keyboard — via this publication’s attached podcast feed above.

Spiraling explores a non-circular intonation: rather than squeezing or stretching (“tempering”) intervals to join into the familiar cycle of twelve notes, I have rationally tuned them to the natural harmonic series — resulting in a subtly more pure intonation, and opening the possibility of playing with large-scale tonal “drift.”

A rational approach to intonation can transform a cyclical progression of chords into something more akin to a spiral — it feels cyclical, but is steadily floating away from its starting point.

Hope you enjoy this new piece. The score, as well as some more detailed context, are below.

Drifting

In the Ben Johnston String Quartet No 9 excerpt I discussed a couple weeks back, he walked a chorale-like progression three cycles1 of pitch away (and back again) through a continuously connected string of consonant harmonies. The resulting large-scale drift creates a subtle, almost imperceptible melting effect:

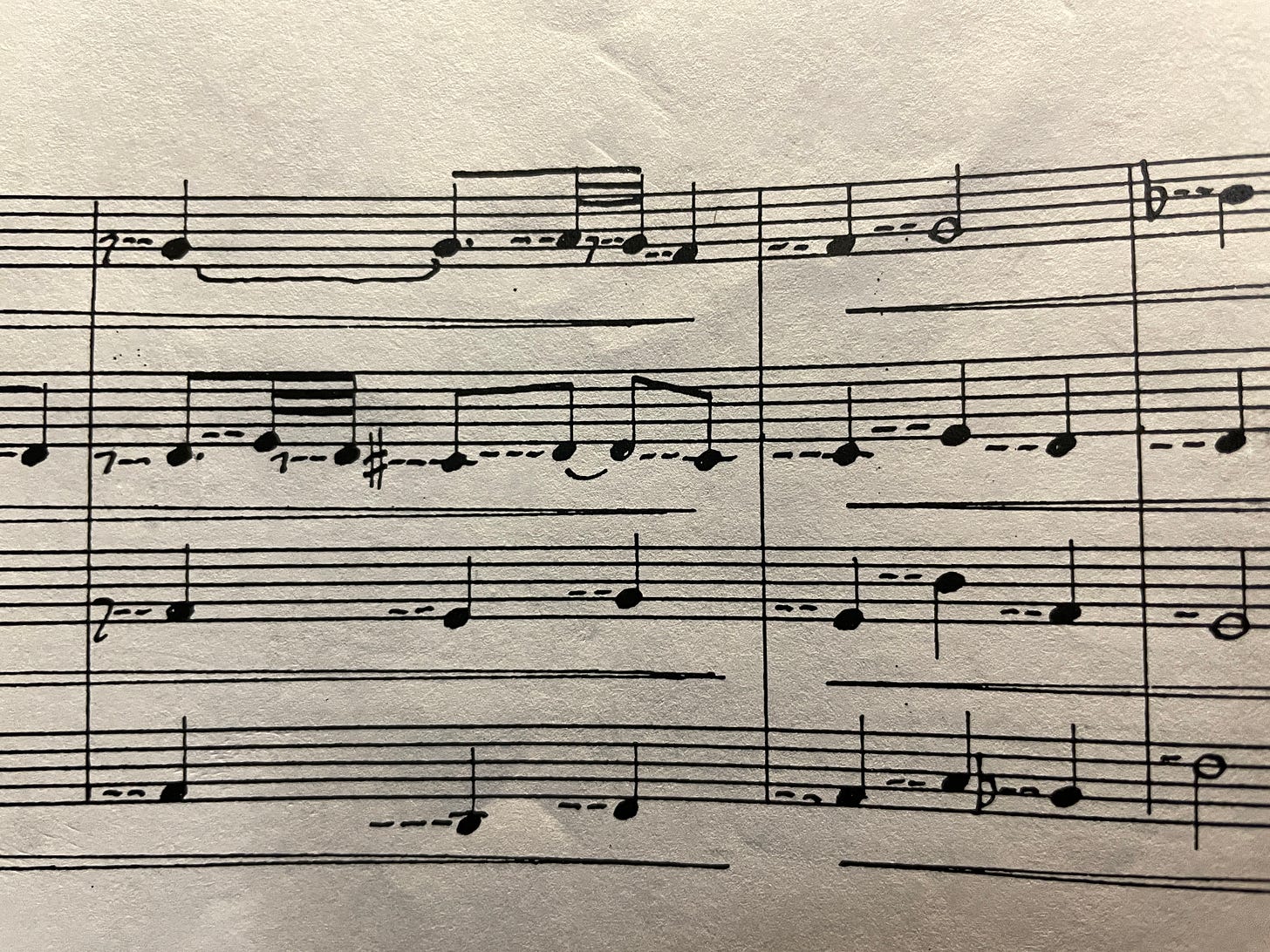

Expressed in standard notation, this passage looks quite intimidating:

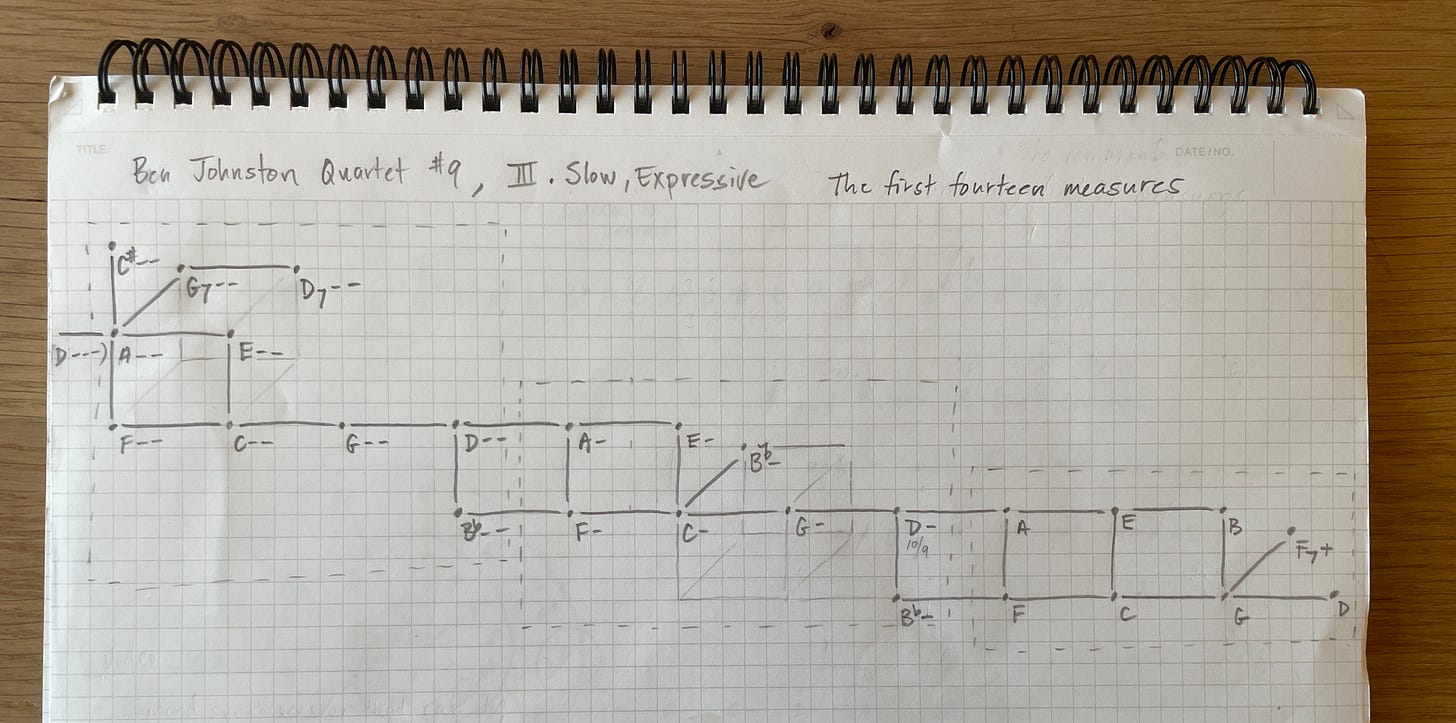

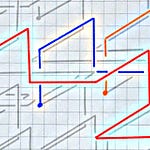

But as I catalogued its pitches2 one-by-one, the organizational logic of this passage came into focus: when visualized as a lattice of relationships, the notes create a beautiful and clearly intentioned structure of intonation:

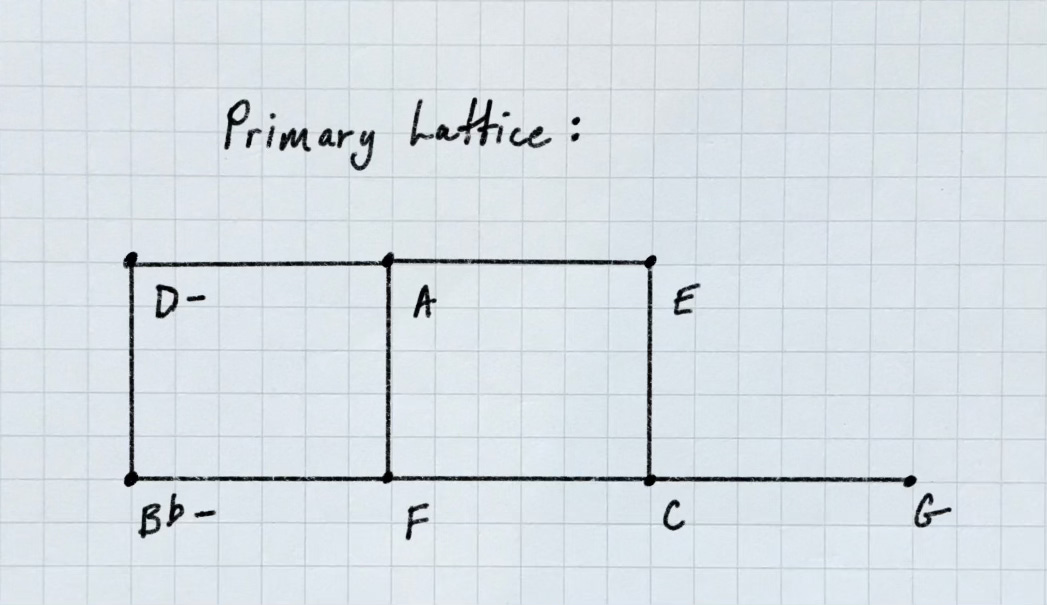

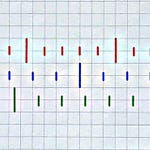

Johnston appears to have pre-planned a basic harmonic strategy: the passage starts in F major, gradually slides down into “F--” major, and then climbs back up. It sets up a simple major tonality and two carbon copies slightly out of phase. That’s all it is.

This architecture is constructed entirely of beams from the foundation of the harmonic series: the natural “major triad” created by 3:2 and 5:4 ratios3.

Spiraling

The generating idea for my own piece was to limit myself to the same set of notes but experiment with non-continuous movement: leaping freely between non-adjacent notes and chords anywhere in the structure at will.

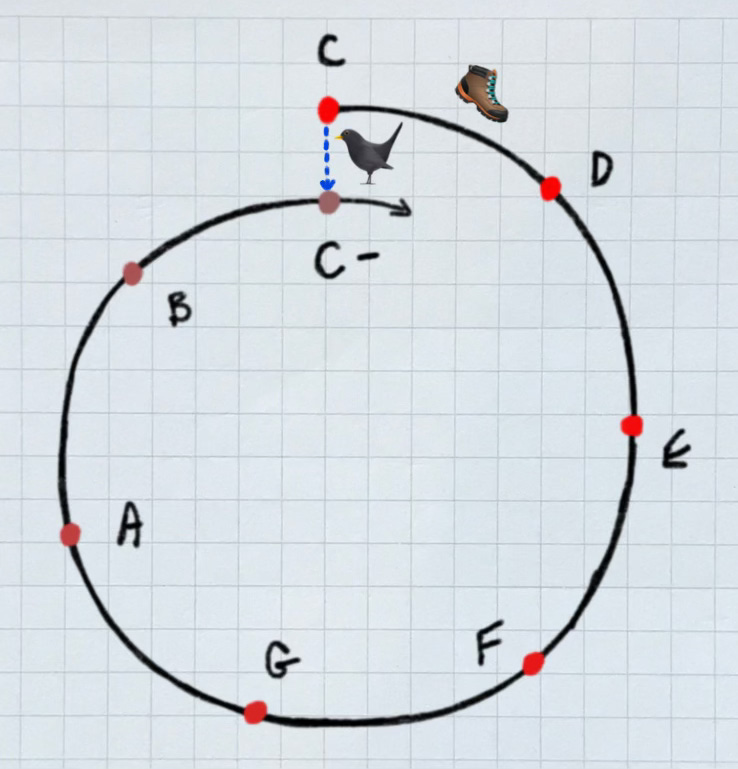

Particularly interesting to me was to compare different versions of the same note. For example: while very close “as the crow flies,” the notes C and C- are actually a considerable distance apart if you travel “on foot,” as Johnston did.

C Major (from measure 1)

C- Major (from measure 11)

Both are precisely in-tune and gloriously consonant: you might not have noticed the shift between them in context. But a step “down” has definitely occurred. He followed that step with another, and then climbed back up again — all “on foot,” all in the space of fourteen measures.

A rectangular 2d or 3d lattice works great to organize the stepwise motion in Johnston’s excerpt. For my piece, visualizing it as a spiral (in octaves) add a separate level of clarity to what’s happening:

Pivoting

The conceptual parallel with emotional spiraling was timely for me: I spent two weeks off-and-on in a state of writer’s block as I struggled to start writing the analysis I had planned of that Johnston excerpt. I had many false-starts as I tried to sympathize with the point of view of the reader. Although just intonation can be explained using elementary mathematics and simple real-world phenomena, it is still very challenging to present portions of it out-of-context in a way that is engaging and digestible.

I was really feeling this challenge. A thought like “this is more difficult than I expected” spiraled to “this will never work,” and ultimately to “this whole endeavor is pointless” (and the deadly “nobody cares”) — with me barely noticing that progression had occurred. Each connected thought feels like clarity (“in-tune,” even 🧐), and yet… they were drifting further and further from center.

It’s shocking to me still, the affect even short periods of non-productivity can have on my sense of well-being. That writer’s block turned into a kind of emotional paralysis.

Thankfully, it was short-lived — I chose to pivot off that spiral and go in a completely different direction: I just started writing some music. The Johnston excerpt’s tuning structure served as a useful starting point. If you’d like to see how my Spiraling could be notated4 using Johnston’s own system for just intonation, here’s the score:

Subscribe for free:

I’m avoiding referring to “commas” at this point because I have yet to write in detail about that concept. Suffice to say that the spiral analogy is a good starting point for the idea: the comma is like the distance between points on adjacent coils of the spiral: a short distance through space, but a considerable distance when taken continuously (the “long way around”).

Johnston’s notational system is elegant, intuitive, and optimized for use with functional harmony. A detailed exploration of it is a little beyond the scope of this post, but in a nutshell: Johnston defined the uninflected pitches of C:E:G, or F:A:C, or G:B:D as being justly tuned in 4:5:6 ratios, and then invented a set of extended accidentals that can be added to notes to indicate relationships between pitches that would otherwise have the same name.

In this excerpt he is mostly using “-” signs, utilizing a range of notes stretching via pure “third” and “fifth” relationships from D at one end to D--- at the other. Each minus sign takes the pitch down 21.5 cents, also known as the distance between two types of justly-tuned major thirds: one arrived at via a 5:4 ratio vs one arrived at via four 3:2 ratios. It’s an 81:80 interval — the “syntonic comma.”

A couple 7:4 intervals can also be seen in the fully realized lattice — they attach to the structure without modifying the overall direction, almost like blue notes… or flavor enhancers? Glimpses through the windows to the third dimension!

This work obviously contains more pitches than exist on a standard piano keyboard tuned to twelve-tone equal temperament — and thus isn’t “playable” in a practical sense on that instrument. But in theory it could be realized in many ways — as an arrangement for instruments with variable pitch capabilities (like strings or winds), using a justly-tuned piano, or using sampled or electronic instruments with microtonal capabilities (as in the above recording).