Poof, you're loose.

The classic "60-second" is low-key just the harmonic series.

Welcome to the parking lot. This is where the drumline warms up before entering the stadium for the competition. Yes, you heard that right: music is a competition, and the goal is to win.

In about an hour our young heroes will arrive at the top of show and be allotted one minute to stretch hands and burn off nerves before judging begins.

The question: how to make optimal use of that precious minute? There have been many approaches over the decades, ranging from the practical to the flamboyant. But to me, the classic “60-second” will always, and forever, be Poof:

Poof was created by Murray Gusseck, the section leader of the Santa Clara Vanguard tenor line, in 1992. At this point he was a 5-year veteran of the corps and had developed some notoriety not just for being an incredible player, but also for contributing fresh material to the standard parking lot warm-up routine. He re-imagined the parking lot as a place not just for exercises, but for musical compositions: “parking lot etudes.” This would be Murray’s last season before aging out and becoming one of the most influential teachers and composers in the history of the activity.

If you could zoom out from this video you might also see caption head Scott Johnson standing in front of the line, at this point in his 3rd season as the director of the percussion program. He had just led SCV to high drums in the previous season. In 1994 he would return home to his Concord Blue Devils, where he would go on to win exactly 4,397 national championship trophies. Wait, no, another one has just come in… 4,398.

What I’m getting at: lots and lots of talent at this particular historical moment. Great hands and great instruction were plentiful. Creativity was flowing — spilling out of the stadium and out into the parking lot.

🎪🚗 The show before the show

The “parking lot etude,” a genre Murray helped invent, is a beautiful example of how a composition can balance opposing use-cases (warm-up vs performance) and intended targets (musician vs audience).

In Poof, the techniques involved start simple and get faster and more complex in graduated steps, just like an instrumental study (and just like.. the partials of the harmonic series 😮). But compositionally, it is very much a “piece.” It’s meant to be performed for an audience.

And the audiences for these pieces became voracious — crowding around the lines, cheering and screaming, making bootleg recordings, and just being generally excited. Many fans would never even enter the stadium for the competition, instead opting to just wander around outside taking in the “parking lot show” — and if Santa Clara was in town, catching Poof was one of the main events.

Poof is the Chopin Etude of the drumline literature.

And the name?… Murray describes the origin of Poof thusly:

SCV’s 60-second, 1992

Some of the guys in ‘92’s line used to plead with Scott Johnson for more warm-up time. Scott’s response was often “Poof! You’re loose!” That’s pretty much the scope of the sheer magnitude and depth of thought that went into the name of this on-the-field warm-up.

Gorgeously self-deprecating. And yet weirdly subversive… up to this point, the title of a drumline exercise typically just described itself: “eight on a hand,” “threes,” “triplet rolls” etc. At the time it felt hilariously irreverent to actually name a warm-up (See also: Martian Mambo, 1990).

🥁🧬 Drumming inside the harmonic series

It only took me 31 years from the first time I saw the score to realize: Poof is the harmonic series expressed as rhythmic values.

This has forever changed how I think about the relationship between rhythm and pitch (not to mention the relationship between single-strokes and diddles).

At the end of this post I’m dropping a new video that simultaneously visualizes Poof as rhythm and pitch. But first a quick primer: in my last article I suggested thinking of a harmonic series as a simple sequence of numbers. I really wish I had understood it like this first — before I ever saw it presented as a series of pitches.

Once I understood the harmonic series in the abstract, I realized that it can apply to much more than just pitch. In fact, looking for the harmonic series in tempo relationships is probably the easiest way to conceptualize it: you can count the beats in a tempo, and there’s a direct correlation between that scale (about 40-200 bpm) and the full range of the human heart rate.

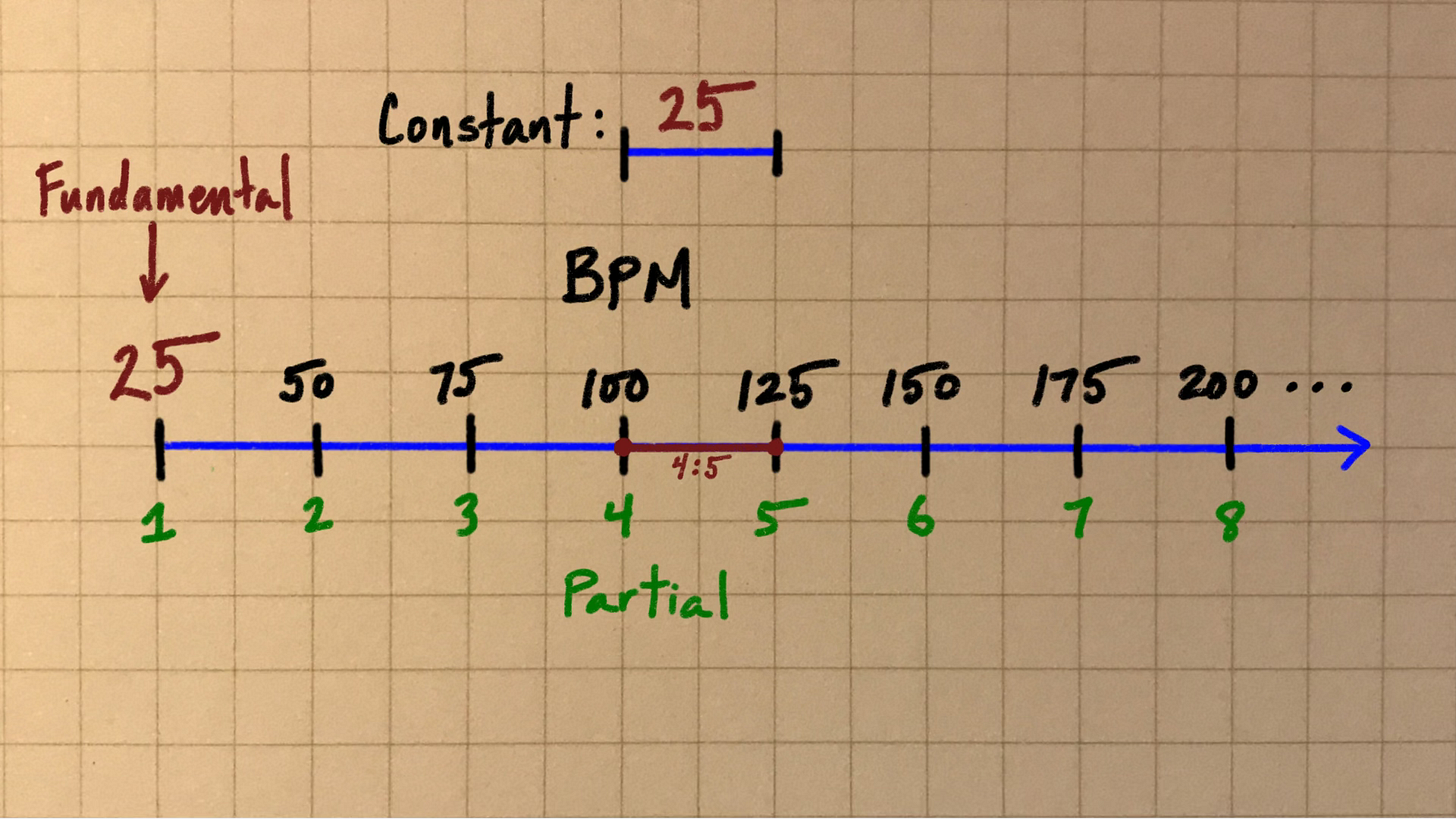

For example: 100 and 125 could be seen as part of a harmonic series with a fundamental of 25. They are the 4th and 5th partials:

This means the tempos 100 bpm and 125 bpm are in a 4:5 relationship. You might also say 125 bpm is “5/4ths faster” than 100 bpm.

If you’re a person familiar with the ratios of just intonation, you may recognize 5/4: it’s a “just major third.” Have you ever thought of a tempo change from 100 to 125 as going “a major third faster?” Now you have, and we can never not be friends from now on. 🥰

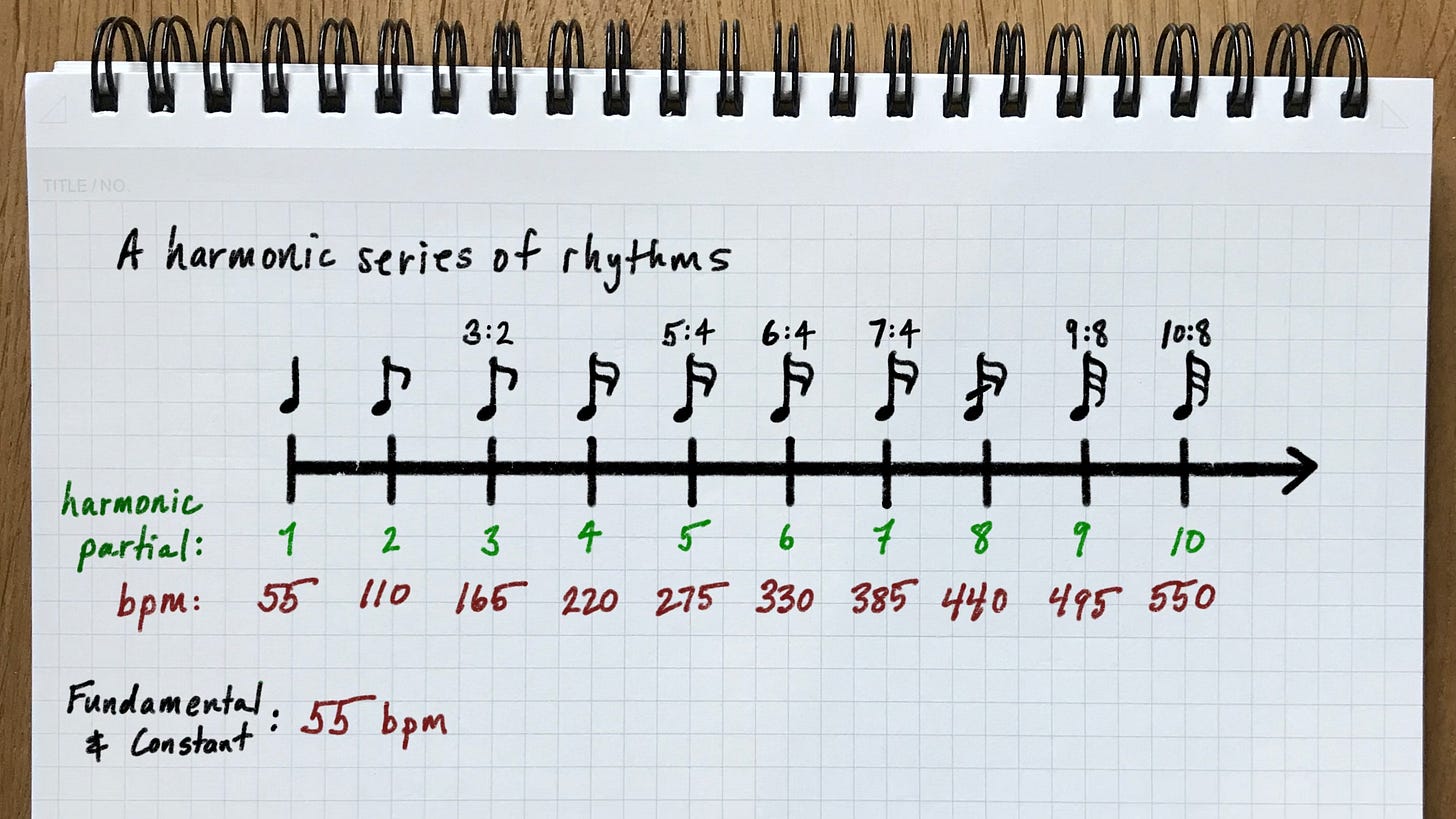

🧬🎵 A harmonic series of rhythms

Poof is a great illustration of the harmonic series partials as rhythmic values.

The scale of rhythmic values starts around 200 bpm — the point where the brain starts to perceive the individual beats of a tempo in groups. It continues until around 1000 bpm, where the notes blend together and we start to experience them as pitch.

Here’s one example of a harmonic series of rhythmic values:

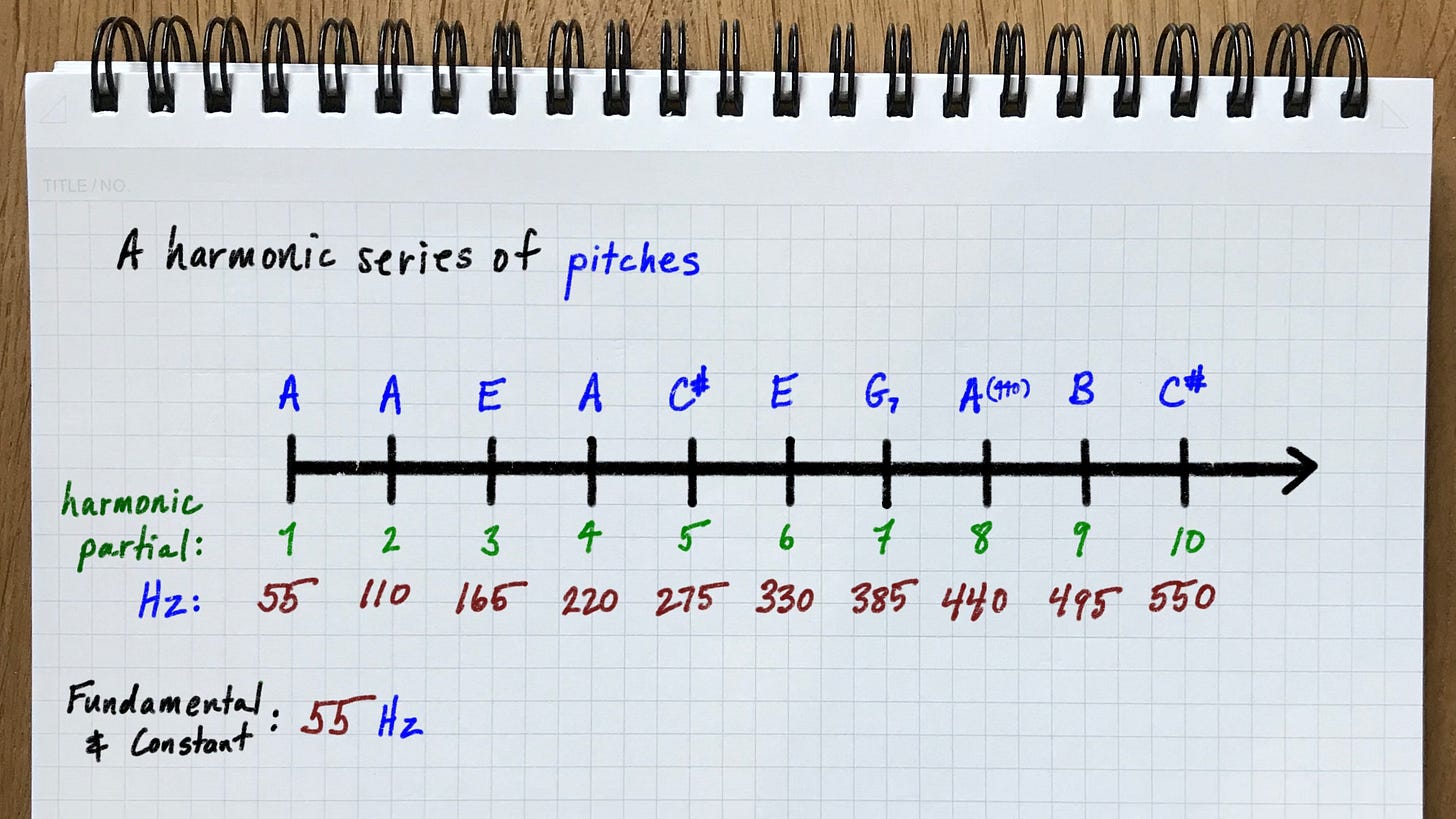

Now, what would happen if we drew the same scale, but 60 times faster: the values would be exactly the same, but in beats per second (Hz), rather than beats per minute.

It would be a harmonic series of pitches:

Quarters, 8ths, 16ths, and 32nds become the note A.

Triplets and Sixtuplets become the note E.

Quintuplets become C#.

Sevens become a G with a mysterious 7 next to it1

Nines become B.

Can you play melodies with rhythms? Yup. Can you make chords out of polyrhythms? Yoooo… chords are polyrhythms. 🤯

So… what’s does all this sound like? Here’s a demo of the sound of both scales, (featuring a special guest):

Do you see how I’m putting my grand unifying theory together piece-by-piece here? Pitch, rhythm, tempo, even structure: our brain tricks us into thinking they are different things, but they’re not.

Here’s the main event:

💨🤲 Poof, visualized:

✍️🪩 The composer/performer

The influence of the “parking lot etude” form on my spongy 14 year-old brain cannot be overstated. These were the first moments where the idea of composing music ever dawned on me, and Murray’s work introduced me to the archetype of the composer/performer.

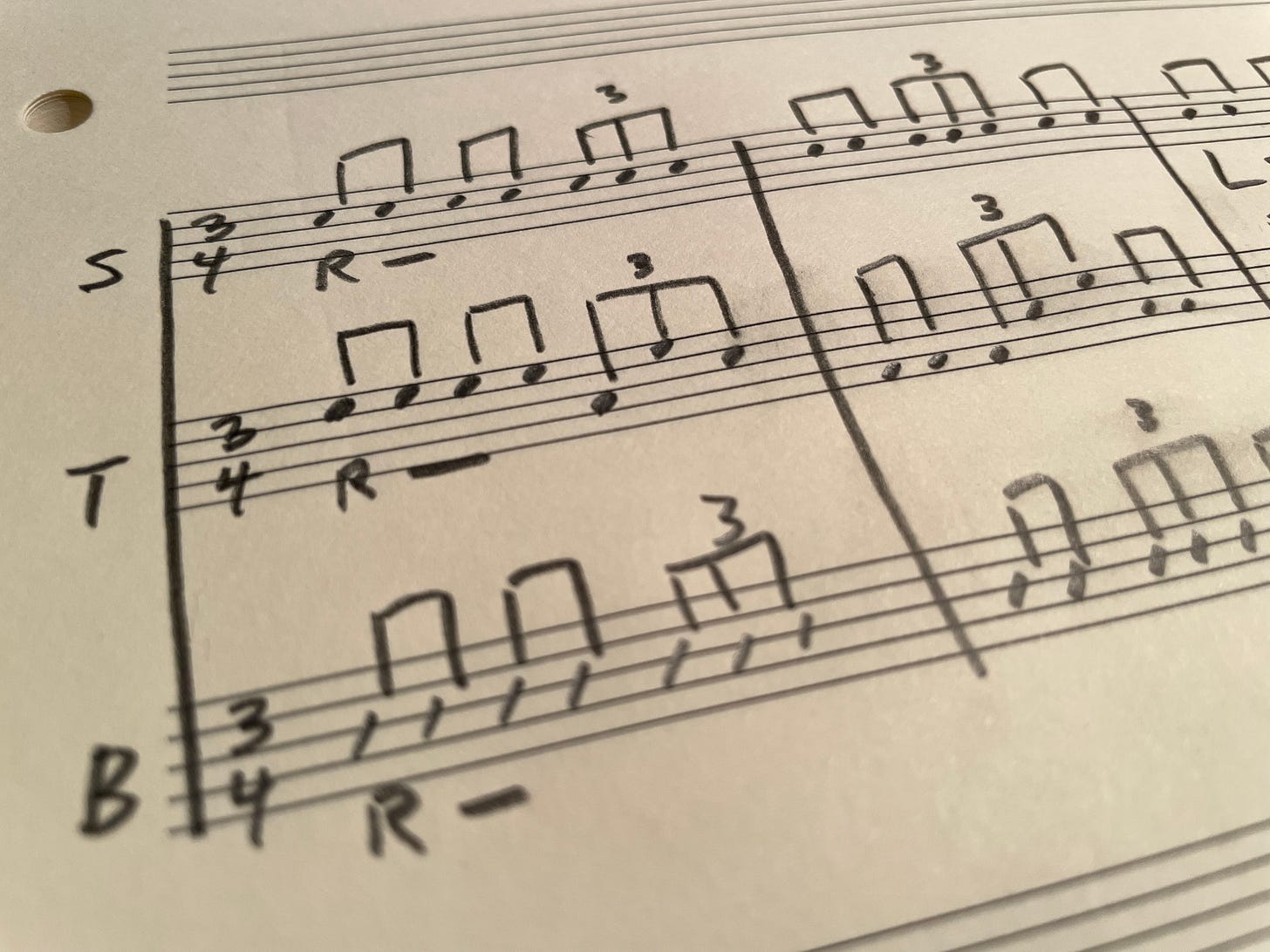

Just as a composer might sit down with a fresh pad of Archives Manuscript Paper and write “SATB” or “Vln1, Vln2, Vla, Vcl” on the staves, I labeled mine “Snare, Tenor, Bass.” This was the perfect format for my own composing: the blank canvas for dreaming up rhythmic ideas and trying to imagine how they might sound played by a line like ‘92 SCV.

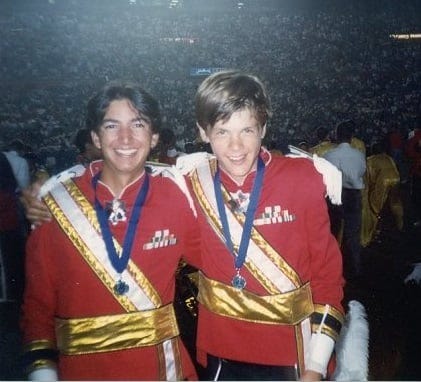

I joined the SCV Tenor Line in 1994 and experienced the absolute terror I mean pleasure of having Murray as my primary instructor. I believe we played Poof for at least part of that season… it may have gotten hosed by finals. We may not have had the hands of 1992’s line, but we tried real hard. Everyone’s a winner here.

🙂 Real confessions: I write these articles because I’m hoping they might make you want to explore my work. The centerpiece of this post is a video now screening in a very famous internet movie theatre called youtube where there is other work of mine you might enjoy. And as always, my music is available in digital, vinyl, and cd flavors from my bandcamp store.

Subscribe for free:

The scholarly fine print

Parking lot etudes are performed at a wide variety tempos, and a line’s sense of the internal tempo relationships will “settle” over the course of a season. In the lot, as long as it’s clean… no one is complaining about the tempo relationships being precise. At least… in the pre-”blast a metronome through a PA system” days they wouldn’t.

In the notated score for Poof, Murray marks the first half at 130 bpm and the second half at 156 (with a transitional 5/4 bar that drops to half-tempo and accells). That’s a 65:78 ratio — not a relationship that would be conceptualized, but rather just learned as two unrelated tempos.

However, in the particular performance I’m using here, the line starts and ends at about 150, with some drift throughout. The accell peaks near 190 and then gradually relaxes all the way to the end. For the purposes of demonstration, analyzing the entire piece at one tempo better reflects the performance practice and allows me to relate all the rhythms to one harmonic series. So I went with that - 150 bpm.

Basically what I’m saying is that if you’re checking my math against the score (lol, no one is doing that. are you doing that? can we be friends), I’m using a little bit simpler of a tempo map than in the urtext.

Acknowledgements

The video at the top of the page is taken from the 1992 Santa Clara Vanguard drumline “yearbook video” — semi-anonymously credited to “Spur of the Moment Productions,” and now residing on the “Drumline Archives” youtube channel. This little relic is comedy gold in a “probably couldn’t be made today” way, and features some truly legendary clips: my favorite being the 92 tenor line ensemble. If you made this video, thank you… I hope it’s ok I’m using it.

Thank you to ODDSound for creating MTS-ESP, which makes experimenting with tuning about a million times easier than it was 5 years ago, and especially to Oli for the support.

Thanks Jim Casella for sharing the lore and fact-checking my drum corps fever dreams.

Okay, couldn’t make it any further into my substack journey without addressing this… The note names here are actually from the notational system for just intonation developed by the composer Ben Johnston. These are not equal-tempered pitches, as they would be tuned on a piano. These are all adjusted very slightly to keep the relationships pure to the harmonic series, which is what I’m demonstrating here. In a previous post I’ve described expressing the harmonic series in western notation as “right picture, wrong frame.” In this case, a harmonic series on low A (55Hz) maps to note names in Ben Johnston’s system nicely — i.e. without a lot of scary extended accidentals. Just the funky 7 next to the G, there. My point is… I’ll get to all of this in gentle, sweet, time.