Rhythmicon

Henry Cowell's Grand Unified Theory

This post is a continuation from last week, which contained my full animated visualization of Nancarrow’s Study #6 for player piano. That post is here:

In July of 1995, iconic London independent record label Mute quietly dropped a mysterious "informational film" about a mechanical oddity of early electronic music onto their FTP, BBS, and Telnet sites.

The video’s unassuming host, introduced as “John Came,” demonstrated a contraption he claimed to be a "Rhythmicon" — the 1930s Leon Theremin and Henry Cowell-designed instrument that is now commonly referred to as "the world's first drum machine."

Mr. Came demonstrates how using a small plastic ball to tap out a rhythm on a metal disc “inputs” beats into the machine, which are then "changed into musical pitches."

He explains how that rhythm can be notated visually on a musical stave rotated sideways, and then translated into a chord… by simply turning the stave ninety degrees counterclockwise.

Finally, after appearing to play polyrhythms from the machine with the strings of his acoustic guitar, the video1 closes with a brief promotional pitch for the CD release of his album Rhythmicon, available on CD or cassette.

Fun fact about this demonstration: that's not a Rhythmicon.

Also, rhythmic values can’t be turned into pitch by turning the notation of a chord sideways (I know, it really seemed like plausible music theory, didn't it?).

Also, that person's name isn't John Came, and John Came isn't a real person.

On the other hand, Rhythmicon the album is very real, and it's wonderful:

The CD liner notes for Rhythmicon give “John Came” an elaborate back-story involving immigrating to Australia from the UK as a child with the "ten pound pommies," and working with the (also made-up) collaborator John Cope and his band "Pnin." By today's standards of misinformation awareness, the whole thing is quite obviously a fun little troll, manufactured as a clever way to market an established artist's anonymous side-project.2

I do miss the 90s. Being mysterious and enigmatic used to be possible, and a viable artist marketing strategy. We used to lie for fun, and get away with it.3 Today, not only do we know every last mundane detail about the identities of our artists, we feel entitled to this information.

But in pre-Google 1995, I have to wonder how many people might have been genuinely perplexed by the joke. Without a way to instantly look it up, did they think the parody might have been about something that was, on some level, real? Was this a joke about some sort of laughably primitive early 20th century attempt at music technology that actually existed? Was the Rhythmicon a real thing that deserved to be parodied?

As it turns out:

There was a real rhythmicon (there were three, in fact!),

It made sick beats.

It was conceived and built to demonstrate a musical grand unified theory — from one of the most influential and forward-thinking composition textbooks of all time.

Essential: New Musical Resources

The tools in the toolbox

Sometimes the force that propels an artist’s work forward isn’t some epic moment of feverish inspiration, or the burning desire to be the voice of a generation. Sometimes all it takes is serendipitous exposure to a new artistic resource.

What is meant specifically by a “resource” will vary greatly from artist to artist. My favorite way to describe it is simply as a “tool in the toolbox,” and the tools of an artist (and of the culture collectively) can glow with potential energy for long periods of time. They can also run out of battery. For example, maybe that particular brown paint used to get you out of bed in the morning, triggering endless hours of creative exploration, but now its expressive potential has dried up. Have you tried blue, Picasso?

In the realm of music, composers today have a ton of musical resources. I would argue way too many4 — they can start to look more like tools of distraction. It’s never been easier to spend an eternity sharpening knives to avoid chopping the onion.

But to composers in the early 20th century, the discourse was more often the opposite: everything that could be done had been done, every chord and rhythm written, every timbre explored.

Could there possibly be any new musical resources with expressive potential left to be discovered?

<CowellHenry1897 has entered the chat>

“Yeah, hold my beer” …said composer, pianist, and writer Henry Cowell, living his best life in 1914 as a fresh-faced University of California at Berkeley music student, and busy using his unique collection of new musical resources to churn out dozens of experimental piano pieces.

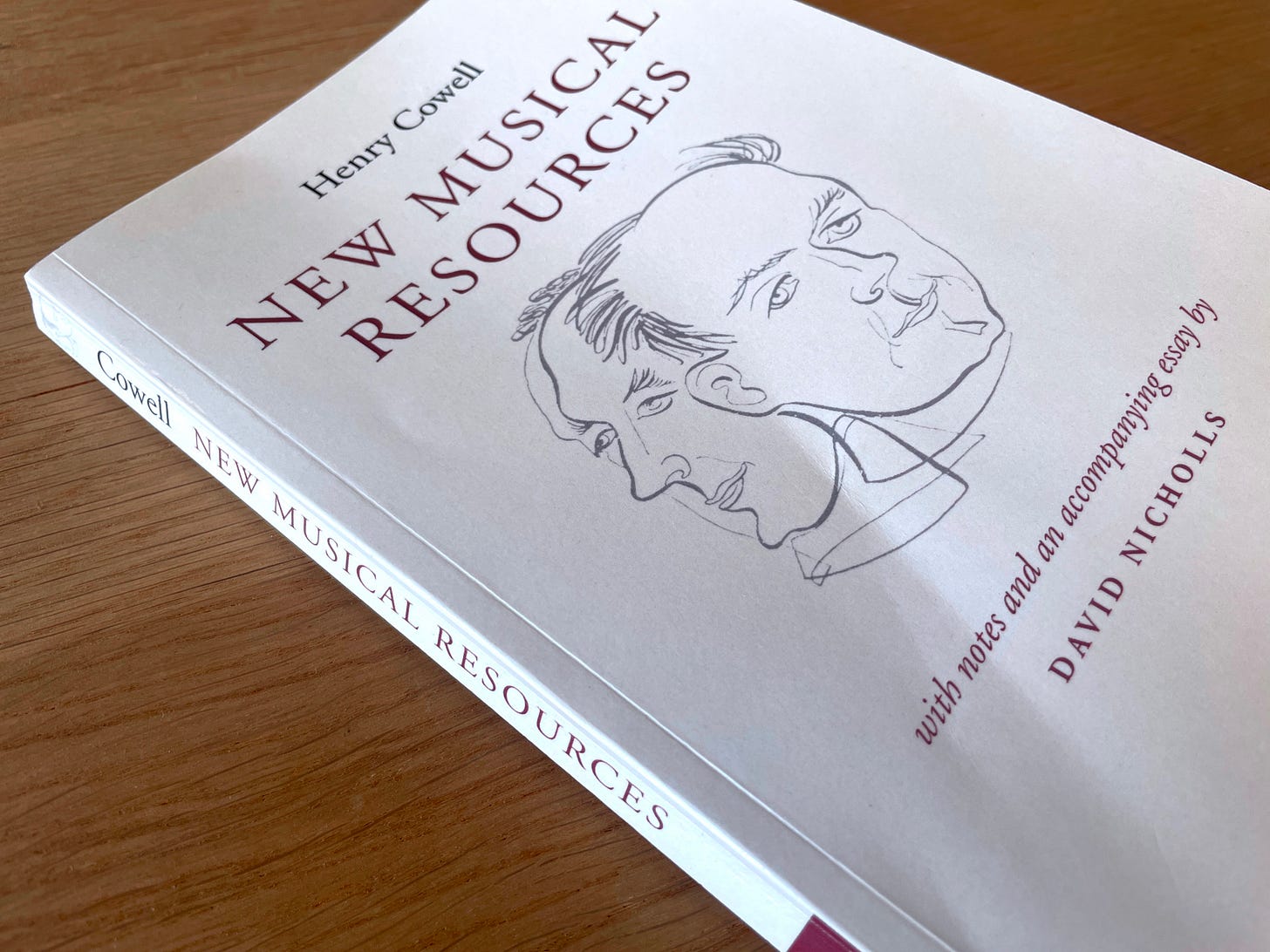

After being encouraged by his composition teacher to write about his methods, he went ahead and wrote a book, New Musical Resources — a humble little volume that would fly under the radar for decades while directly or indirectly influencing composers who created some of the most original music of the 20th century.

And I know it can influence you, too. It’s fascinating context for listeners of contemporary music, and a must-have for composers. The book has three main sections:

Tone Combinations: Why I converted to the Harmonic Series (life changed!)

Rhythm: You’ll never believe this one shockingly simple way to make your rhythms more interesting (treat them like pitches!).

Chord-formation: Are you tired of the same old triads? Make the switch — to Tone Clusters™.

He starts by introducing the natural harmonic series, a fundamental unit of time and its mathematical multiples. The influence of the harmonic series on all aspects of music becomes the crux of the book — a universal foundation of measurement upon which his grand unified theory of pitch, rhythm, and harmony is built.

In barely over a hundred pages, there are enough new ideas for lifetimes of compositional exploration (in fact, Cowell never even got around to trying out many of his ideas in his own music). Some highlights:

Orchestrating with a conscious mindfulness of the harmonic series offers a composer a whole new palate of timbre, or “tone-quality”. This simple point, made by Cowell in just three pages, predicted the entire compositional movement of spectralism a half century later.

Rather than continually building up a single harmony by combining successively more and more individual tones, one might combine multiple chords.

For example, a composer might juxtapose two simple triads, separated by an interval from the harmonic series — he calls this “polyharmony,” which avoids the “undue complexity” of adding many tones to a single harmony.Conversely, when “undue complexity” isn’t undue at all, but actually desired, “tone clusters” offer that expressive potential. This technique made Cowell’s own music famous (and caused a lot of really dumb scandal).5

Pitch, rhythm, and tempo are all just regular durations of time, manifested by sound. So it follows that pitches, rhythms, and tempos could be organized into scales (and even played like a piano).

😮 …that last one. That one’s really interesting. We spent hundreds of years gradually broadening the horizon of possible pitch choices… why are we so lazily imprecise and unimaginative in choosing tempos? What is “allegro” and how much meno “mosso” is “poco” anyway? The key of a Beethoven symphony is not up for negotiation, why is the tempo in dispute? What if we moved through tempos with the same agility and accuracy that we traverse the piano keyboard? What if we juxtaposed them two and three at a time?

What would that sound like?

In 1930, when New Musical Resources was finally published, that wasn’t an easy question to answer. Most musicians’ ability to perform material in complex tempo relationships was limited, and mechanical instruments for demonstrating them didn’t really exist. There was, of course, the metronome — but trying to demonstrate a scale or chord of tempos on a metronome would be like trying to play a harp with one string.

But Cowell had an idea, and it’s right there in the text:

It is highly probable that an instrument could be devised which would mechanically produce a rhythmic ratio, but which would be controlled by hand and would therefore not be over-mechanical. For example, suppose we could have a keyboard on which when C was struck ; a rhythm of eight would be sounded ; when D was struck, a rhythm of nine ; when E was struck, a rhythm of ten. By playing the keys with the fingers, the human element of personal expression might be retained if desired. It is heartily proposed that such an instrument to play the scale of time-values given at the end of this chapter be constructed.

- New Musical Resources, page 65.

<ThereminLeo1896 has entered the chat>

The Real Rhythmicons

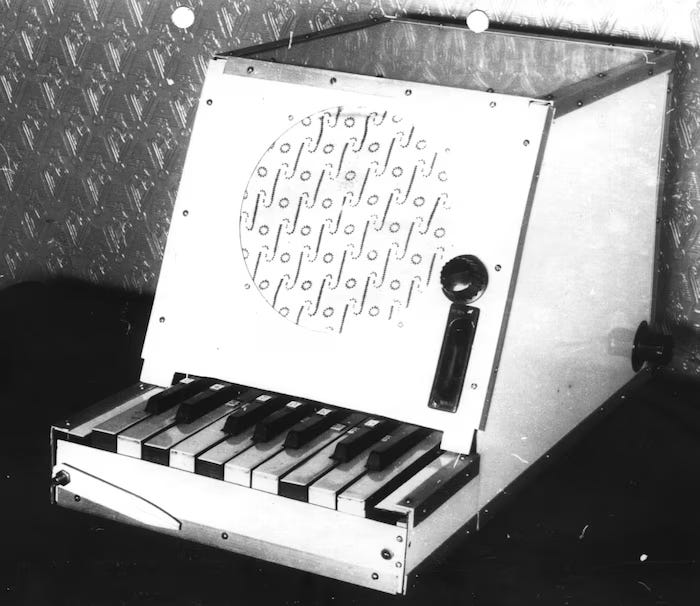

There were only three ever made.

Leon Theremin built the first Rhythmicon for Cowell (at the “friend price” of $200!) in the early 1930s. That one is now in a box at the Smithsonian.

The second model reportedly ended up at the Stanford psychology department, where some shrink put it out with the trash.6 It should be of no surprise to anyone that over in Palo Alto they have no interest in being the caretakers of weird-looking gadgets made by Cal alumni.

The third wasn’t built until thirty years later. It is now safe in the hands of Andrey Smirnov at the Theremin Center of the Moscow Conservatory. Smirnov revived it in 2004 and has been its loving steward ever since. Here’s a video of the first time he ever turned it on7, which made me quite anxious honestly because it sounds like it’s going to either explode or chop his finger off or both. Andrey, keep your hands away from that thing!

But… It works!

How it works

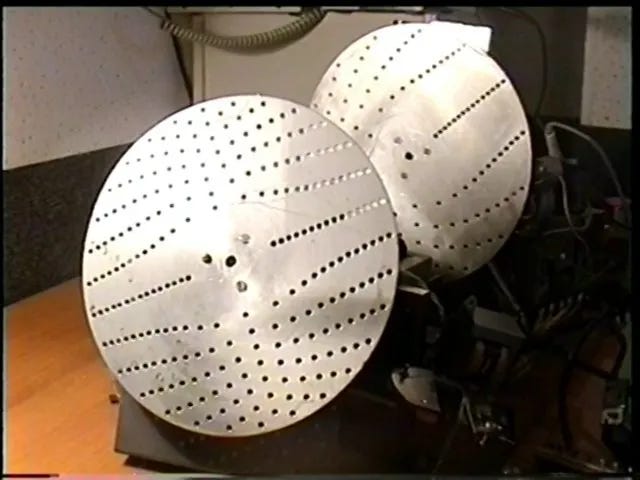

Two metal discs spin in parallel.

In back, the “pitch wheel,” spins faster. In front, the “rhythm wheel” spins much slower.

The discs have sequences of holes arranged in concentric rings.

The number of holes per ring corresponds to a partial of the harmonic series, and pointing perpendicular to each ring of holes is a tiny lamp.

As the back disc (the “pitch wheel”) spins, light from that ring’s lamp comes through the holes in pulses… because this disc is spinning very fast, the pulses are very fast — a frequency range of musical pitch.

The pulsing light that gets through the pitch wheel then gets chopped up again by the front disc (the “rhythm wheel”). Because this disc is spinning very slowly, the pulses are slow — a frequency range of musical rhythm or tempo. They go all the way down to about once per second.

The light that makes it all the way through both wheels lands on a phototube, connected to an amplifier that translates the electric signal into sound.

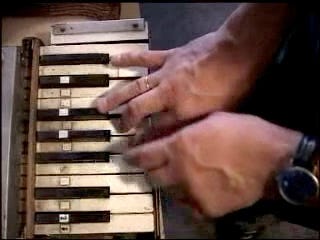

The keys on the keyboard “play” the lamps, thus making the instrument performable.

Because there are as many lamps as keys, this thing is polyphonic — it could play up to 16 notes/beat divisions at once. This would allow Cowell to demonstrate chords, intervals, and scales of rhythm to his heart’s content.

Here’s Mr. Smirnov and the Rhythmicon doing just that!8

Also:

There was absolutely no reason to expect this thing would sound this good?!

It sounds so good!! Each note is this deliciously rich little analog squeak… the kind of sound that might remind you of those breathtakingly expensive modular synthesis systems. Today we can make a million sounds like this digitally… but it would be so hard to get that same depression-era sonic character. Do you know what I mean??

Music shot through spinning discs! Where did that idea even come from?

<HelmholtzHermann1821 has entered the chat>

Sirens and Samplers

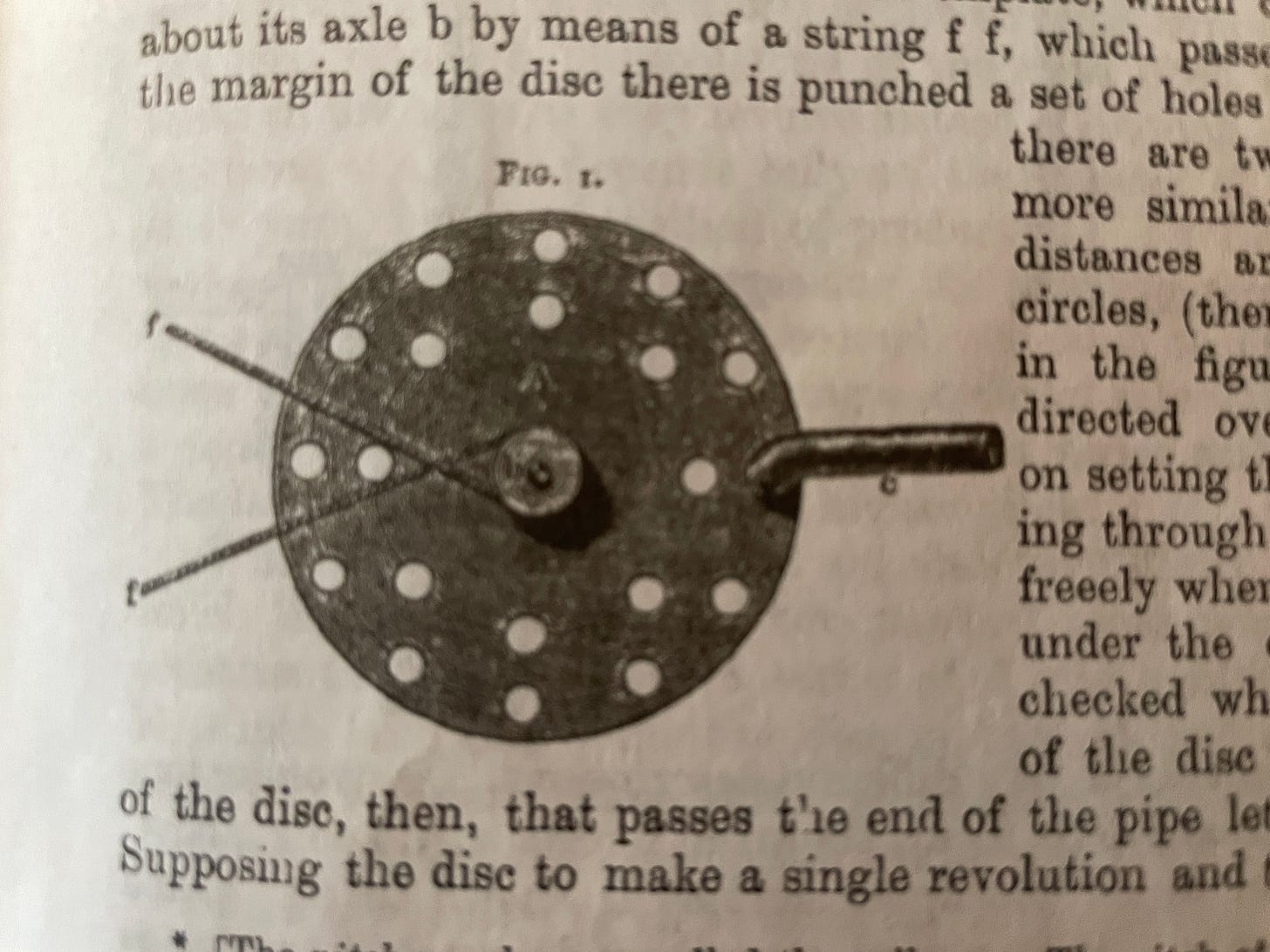

As brilliant as the concept was, Theremin wasn’t the first musician to punch holes in a disc and spin it to make sound. As I researched the Rhythmicon I kept expecting to run across some mention of its design being modeled on the Helmholtz Siren… a device invented by Herman Helmholtz sixty years earlier and outlined in his essential book On the Sensations of Tone.

Helmholtz used his sirens to conduct precise experiments regarding the ratios between musical pitches, phasing, interference effects, the harmonic series, and more. Think of it like a Rhythmicon but with only the pitch disc — and instead of translating pulses of light into sound (through electronic amplification), it used puffs of air, which created sound naturally. No amplification necessary.

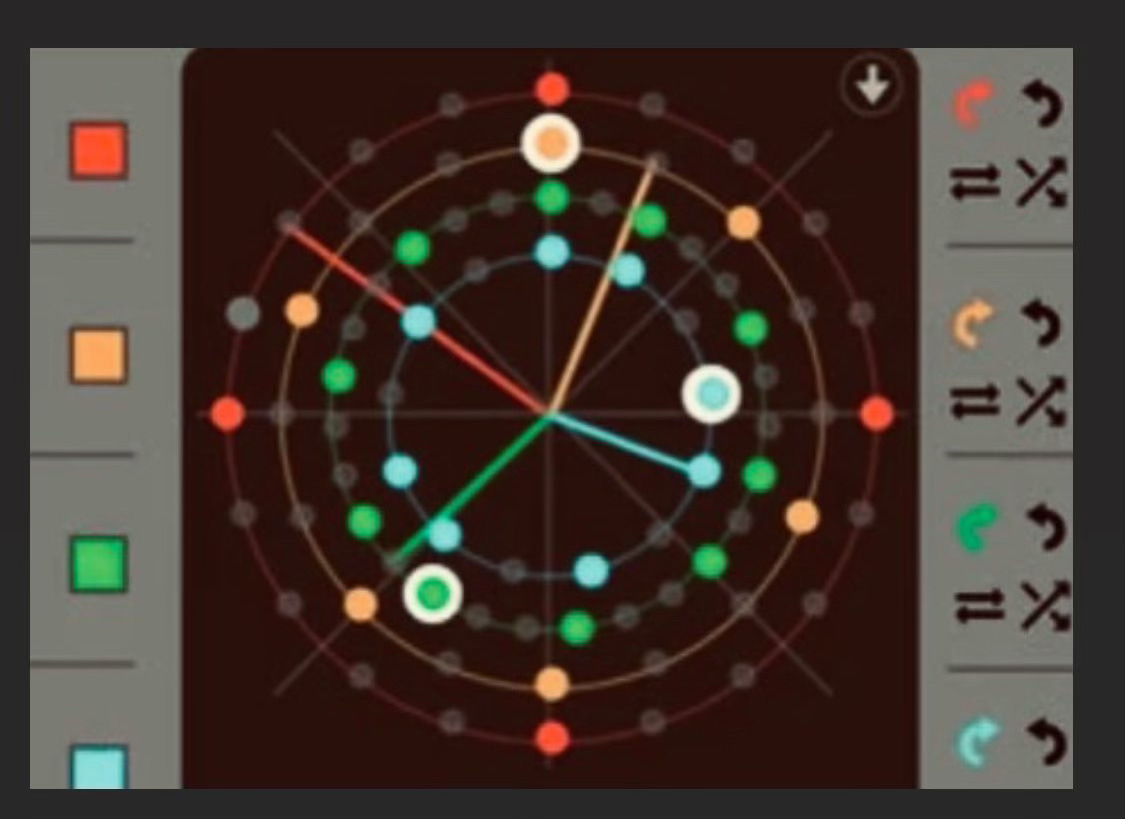

The idea of holes punched in concentric rings on spinning discs has even caught on in the world of electronic music recently. We call them Euclidean Sequencers:

Before I even knew about the Rhythmicon, I had a mental image of what the sound of Helmholtz’s siren might sound like if it were slowed down to make the puffs of air individually audible. It wasn’t unlike those little analog squeaks. I imagined it as very staccato notes on a piano. And I wrote a song about it, and it goes something like this:

If that’s a drum machine, it ain’t no 808

And so “the world’s first drum machine” was born. The term is a bit of a misnomer, honestly. Drum machines don’t equate ratios between rhythms with pitch, and aren’t played by a chromatic keyboard. As an instrument, the Rhythmicon operates more like a keyboard sampler.9

But what an interesting instrument it could have been. Cowell’s buddy Joseph Schillinger once calculated that it would take 455 days, 2 hours, and 30 minutes to play every possible combination available on the Rhythmicon, assuming an average duration of 10 seconds for each combination.

Put that in your MPC and sample it.

<GannKyle1955 has entered the chat>

In his Homage to Cowell (Tuning Study No. 2)10 from 1994, the composer Kyle Gann did exactly that — he translated the concept of the Rhythmicon to a modern sampler by loading a single drum loop across its entire keyboard range, and then devising a tuning to trigger it based on two related harmonic series.

Each key not only pitch-shifts the drum loop (in satisfying harmonic ratio relationships), but simultaneously speeds it up or slows it down —always in perfectly proportional ratios that create surprisingly funky and expressive patterns.

In this short work we discover a perfect example of one very effective musical application of Cowell’s “scale of tempos” idea — the underlying tempo, always manifested by the lowest pitch, regularly changes in coherent geometric proportions, creating an underlying tempo structure every bit as satisfying as a musical melody.

But there is an elephant in the room — Gann performs this piece live by holding down chords on a digital sampler (and the score notates it as such)… but to realize this music on real percussion with live players would require musicians with highly evolved rhythmic skills. Not out of the question today but very, very difficult.

In Cowell’s day the idea of performing the type of rhythms created by the Rhythmicon was so far-fetched that he didn’t even entertain the thought. He assumed it was impossible, and said as much:

“Some of the rhythms developed through the present acoustical investigations could not be played by any living performer ;

But! As ever… he had ideas:

but these highly engrossing rhythmical complexes could easily be cut on a player-piano roll.” - New Musical Resources, page 65

< NancarrowConlon1912 has entered the chat>

Cowell spoke, and Conlon Nancarrow was listening.

After several of his early compositions for live musicians had brought him little success and lots of frustration, Nancarrow spent a pivotal year living in New York City around 1939, where he made his most important musical contacts, and found his copy of New Musical Resources.

In his own words:

“[Cowell’s] book New Musical Resources is probably the most influence of anything I’ve ever read in music. In fact, I just reread it again. I hadn’t read it in many years, I thought maybe now I wouldn’t think so, but I still think it’s a very good book. And there are still a lot of ideas in there that haven’t been carried out. There are two or three places where he mentions that something would be interesting, but it could only be done on a player piano. And he never did it! That’s the thing that surprises me.” — Conlon Nancarrow, interviewed by Kyle Gann, 14-16 September 1989.

Forced into exile for his communist party affiliations, it would be seven years spent as an American ex-patriate in Mexico City before returning to New York in 1947 for the purposes of realizing that dream — to find a player piano and a punching machine, and start finding out what all these “impossible” rhythms might sound like.

The player piano, along with Cowell’s other suggestion of juxtaposing multiple tempos at the same time, would provide unlimited sustenance to Conlon Nancarrow’s entire musical output from that point on. His fifty-odd player piano rolls are widely considered to be among the most original and influential music of the 20th century.

“His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, perfectly constructed, but at the same time emotional… for me it’s the best music of any composer living today.” - György Ligeti, on Conlon Nancarrow, 1981

Study #6

What makes the bass wonk — 1) A new musical resource

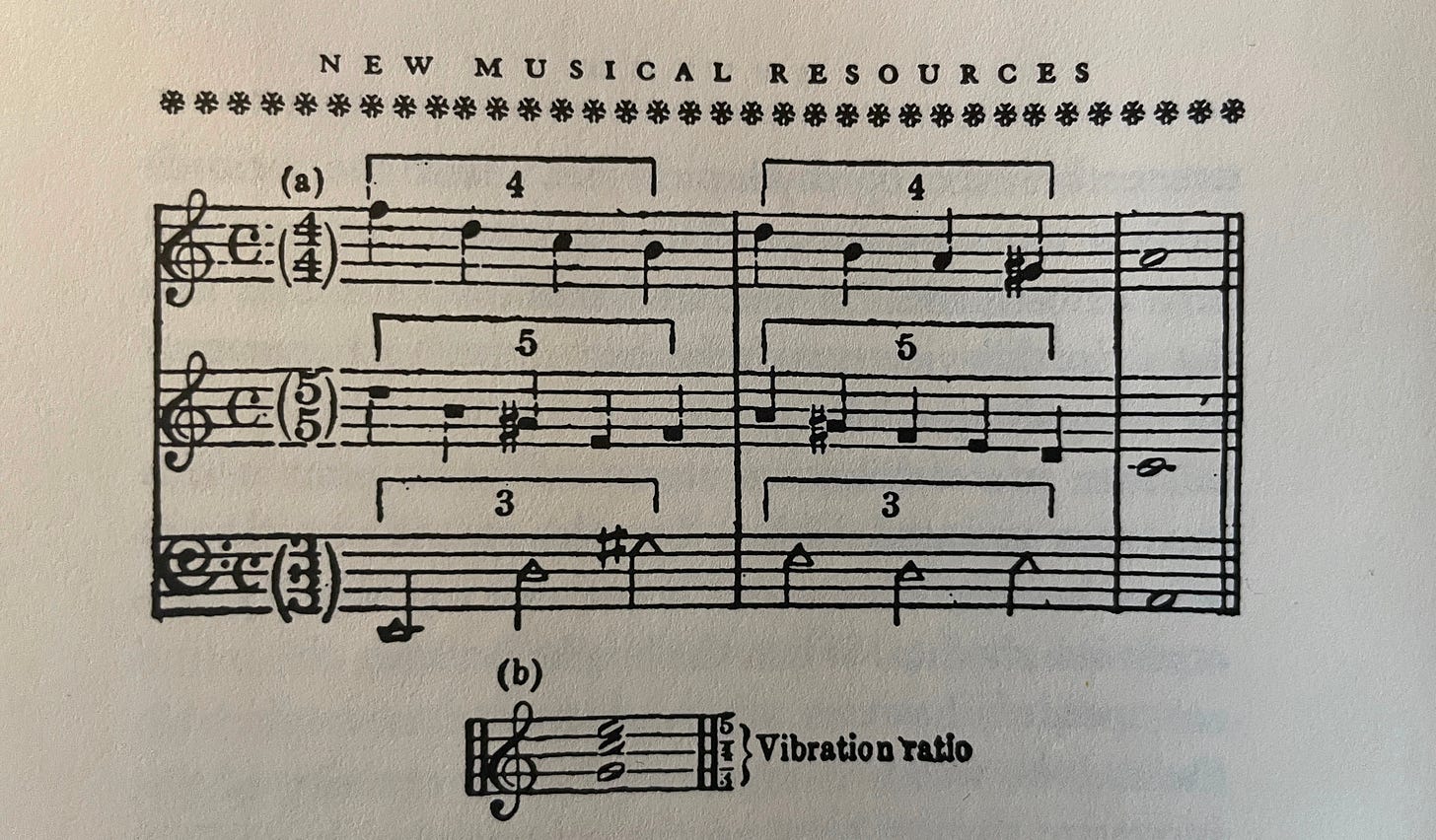

The central rhythmic idea for Study #6 arrives at Nancarrow’s doorstep, fully-formed, on page 52 of New Musical Resources:

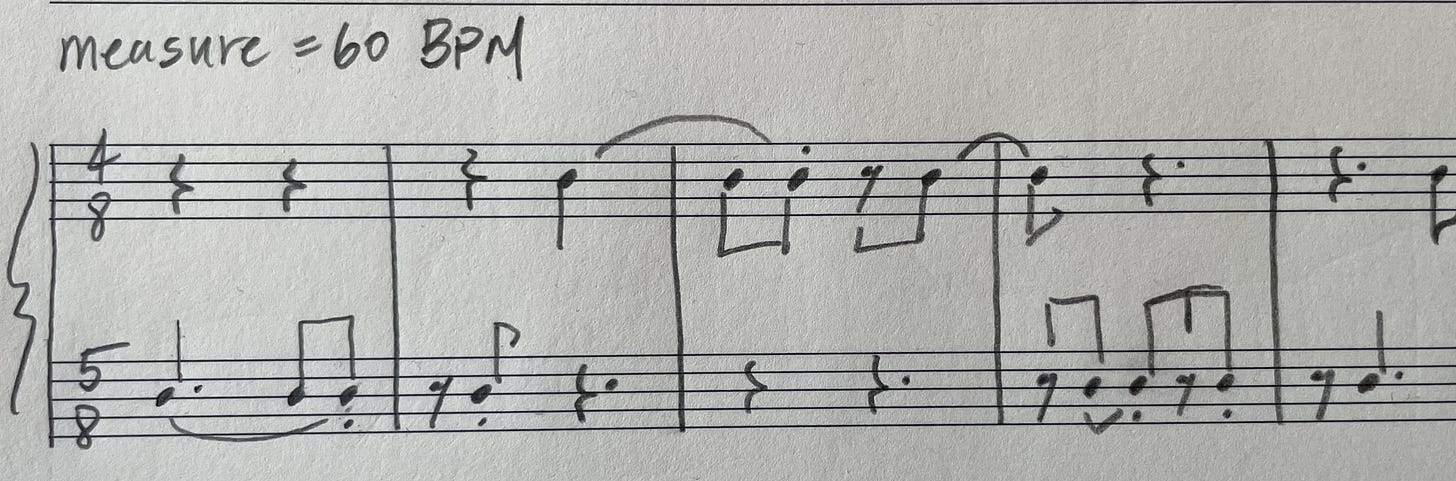

Three pulses, in a ratio of 3 : 4 : 5 are layered on top of each other. They repeat once per second: also known as sixty beats per minute.

I’ll never get bored of demonstrating how a rhythmic pulse, sped up, turns into a pitch. In this case, that 3 : 4 : 5 ratio corresponds to a pure-tuned major triad, in second inversion. Call it (as Cowell does above) G, C, E:

Nancarrow’s framework for Study # 6 is identical to Cowell’s example, down to the ratios involved. The melody lines use the “third notes” (as Cowell would call half-note triplets), and the bass line alternates between the “fourth notes” and “fifth notes.”

The fourth and fifth notes of the bass line are split between staves, which makes the proportional rhythmic shifts more visible.

Now we can imagine this bass line being performed on a Rhythmicon.11 Pressing C activates the fourth notes, and pressing E the fifth notes. When the melody comes in, it’s rhythm is equivalent to G — third notes.

The two tempos of the bass line never overlap. This fact, combined with the irregularity of the points in the measure where the keys are triggered, are what creates that marvelous off-kilter effect.

What makes the bass wonk — 2) An old musical resource

The other element of Study #6 that makes that bass line so slippery is a musical resource that is so old it’s new.

Isorhythm is a simple concept that creates self-generating complexity. Possibly the earliest example of algorithmic composition, its use goes all the way back to 13th century French motets (even though it wasn’t dubbed “isorythm” until 1904).

Here’s how you make one:

Choose a repeating rhythmic figuration. Check how many notes there are per cycle.

Now play, in that rhythm, a melody with a different number of pitches.

Stand back and watch the melody go out of sync with the rhythm.

Historically, the rhythmic pattern was referred to as the “talea” and the pitch sequence as the “color.” That’s confusing, and I don’t like it one bit. But here we are.

Study #6’s color is a bass line consisting of fifteen pitches. It’s talea is sixteen notes (four groups of four, outlined by the alternation of those two tempos in a 4 : 5 relationship).

And here it is. You’ll see how the “talea” always starts on the far left. One cycle is the full width of the screen. Whereas the “color” is one note shorter. Its starting point keeps sliding to the left.

If Nancarrow were to let the relationship between the “color” and “talea” play itself out naturally, they would eventually rejoin on their own. In his comprehensive book The Music of Conlon Nancarrow, Kyle Gann names this the convergence point.

But several times in the course of the study, Nancarrow “cheats” that convergence point — for example, by skipping several notes of the pitch sequence, effectively “fast forwarding” to it:

For all its charm, that bass line is a particular kind of maddening. A repeating ostinato with a palpable sense of groove and charming swing, you can get it stuck in your head, but you just absolutely cannot hum along to it. It constantly slips through your fingers.

Fun with music marketing: just add misinformation

One last fun fact about John Came’s Rhythmicon, the album: it contains no Rhythmicon.

And the music makes no discernible use of Cowell’s ideas, either, as far as I can tell… Tempos are “set it and forget it,” and there certainly aren’t harmonic rhythms, multiple tempos juxtaposed on top of another, or anything like that.

Given that Mr. Came is an invented person who doesn’t give interviews, I guess we’ll never know why he named it Rhythmicon, or if that “instructional video” was meant to relate on any deeper level to the album’s creation. I’m cool with it — sometimes I miss all the not knowing and slippery ambiguity.

And it’s a really good album.

🔉👋 Subscribe for free:

Obvious now… maybe not quite so obvious at the time…? Or at the very least not so immediately debunk-able?

The identity of the artist(s) behind this record went through several phases of speculation, the most seemingly plausible being that "John Cope" was actually Vince Clarke from Erasure, which tracked — Erasure were, and are, lifetime Mute artists. The only music video from Rhythmicon is still mislabeled as "John Came (Erasure)" on YouTube (but debunked in the comments).

In a fun bit of music genre irony, that music video appears to have aired originally on MTV's "Alternative Nation," which is hilarious given that its creators made the album in direct reaction to "the tedium of mid-90's indie guitar music." (source)

John Came is now confirmed as electro pop duo David Baker and Simon Leonard, who's Kraftwerk-inspired music has been released under the names "I Start Counting," "Fortran 5," and "Komputer." It was re-released by Mute in 2023. Truly, love this album! Highly recommend.

https://www.musicradar.com/news/aphex-twin-wanted-to-buy-a-submarine

As a person exploring microtonality with computers in 2025, the “toolbox” of new scales suddenly available is particularly breathtaking… and paralyzing.

Tone clusters, (along with his technique of performing directly on the strings of the piano, which he doesn't explore in the book) is what he's best known for, which to me is really unfortunate. The fixation on the “scandals” he caused by his naughty abuse of the piano seem to have overshadowed his enormous and substantial contribution to other areas of musical thought.

But I get it… why put the mental energy into watching The Wire when Real Housewives is on.

Full video here, from the Ableton Loop conference.

What the World Needs Now: A truly cross-platform Rhythmicon emulator with full sampling capabilities! Here are several things to try:

Shoutout to Ian Dicke and Novel Music’s Aisles, which is a wonderful Max for Live device inspired by the Rhythmicon.

Brilliant software instrument and effects creator Rex Basterfield created a sim-rhythmicon which looks absolutely amazing but I can’t try it because it is windows-only.

The original “online Rhythmicon” appears to exist on a decade-old website, but is a java applet and is therefore now unusable.

The keymap of the real Rhythmicon was actually laid out in a harmonic sequence. I’ve emoji-depicted it triggering a normal chromatic scale just to be less confusing.

Hey Chris: Fairly new as a reader to Substack and really enjoying your posts. Your own work shared here had a delightful retro quality: a kind of frontier steampunk post-modern sound. It's nice to hear advanced compositional techniques fulfilled with very traditional timbres - a bit like alternate musical history.

I teach at Berklee and have been exploring Schillinger's legacy in the pedagogy here - it shows up in odd

places like a homeopathically reduced tincture. So the connections between Cowell, Theremin and Schillinger are of particular interest to me. Some of these polyrhythmic textures are very reminiscent of Schillinger's rhythmic ideas.

Thanks, Chris.

Another great post. So full of musically informative and inspirational stuff!