EDIT — 12/3/2024

The Primer is back in print! — it can be ordered here for $15 through Ingram Spark.

To start, a quote from Art & Fear:

“Once you’ve noticed the relationship of a line to the picture’s edge, you can’t unnotice it. Before that moment the relationship doesn’t exist. Afterward, it’s impossible to imagine it not existing”

Today’s textbook is just eighty photocopied pages. It introduced me to the musical equivalent of the “edge of the canvas” — a profound way of thinking about music that is as ancient as it is new.

Can confirm: it is now impossible for me to imagine the picture’s edge not existing.

In December 2021 the New York Times ran an article about former pro skateboarder Duane Pitre, who had given up a flourishing and potentially lucrative skating career around 1997 to pursue music, and eventually become a composer. He now creates music with just intonation as its organizing principle.

I woke up that morning with the link to this story already in my inbox — “isn't this that tuning thing you keep talking about?"

I held my breath as I read. Indeed it was about that thing. Pitre had even taught himself that thing the same way I had: by devouring a thin, spiral-bound book by David B. Doty called The Just Intonation Primer.

Knowing the profound impact it had on me, I would love to see where it takes any musician who opens it… I say this whether you are a professional or amateur, no matter what instrument you play, and possibly even if you aren't a musician at all.

The pages of The Primer look intimidating, but require only a rudimentary knowledge of musical concepts and no math skills other than simple arithmetic. It could be a fascinating and pleasurably challenging journey for anyone who wants to get to the bottom of that age-old "music is math" claim.

Multiple Discovery - the Agony (the Joy)

I want to touch on the Times article and my experience of reading it, as the feeling of that moment has become a familiar one that I try to be honest with myself about. I'd call it anxiety but that doesn't seem right — for me anxiety is like the drive to escape a burning building, whereas this feeling more resembles the urge to run back into that building to save a puppy. It's an urgency. Very uncomfortable, honestly: a tightness all the way down the front of my body. "Don't just sit there… do something."

My rational side is excited… "I'm not alone!" And yet my maladaptive side is panicking… "Someone is beating me to it! This one was gonna be my thing!"

Reading about Pitre’s path was like looking in a mirror (in the least-creepy way possible, and minus the skateboarding part). The move to nyc, the meeting other musicians, the focus on playing as much as possible and re-focus on composing, and finally the stumble across the “picture’s edge” (his introduction to just intonation was Lamonte Young's The Well Tuned Piano; mine was a piano sample library featuring an option for tuning to the harmonic series).

This triggers a breathless search for answers:

“It felt like confusion, in the best sense,” Pitre said. “I began asking people what just intonation was, and they said it was nature’s tuning system. I didn’t want the New Age explanation. I wanted the science.”

🙋♂️ SAME

He pored over rudimentary websites, read scholarly essays and ordered a spiral-bound workbook called “The Just Intonation Primer.” He tackled its mathematical models like a college student grappling with calculus and internalized just intonation’s axioms.

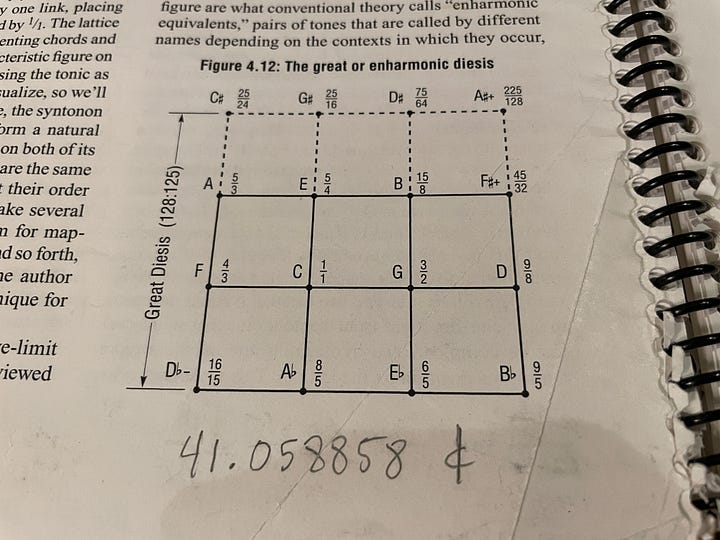

At this point I already felt like I was reading about myself, but then… my eyes landed on a photo of Pitre's Primer, and my jaw dropped. He’s got it open to page 43. I've spent unquantifiable amounts of time staring at, thinking about, and scribbling on, page 43.

It's the crux of the book for me, and apparently for him as well — look, he's drawn all over his copy too! He's pointing at it! I've excitedly shown this book to countless people in my life, usually opening straight to page 43 and pointing at that same diagram in precisely the same way.

A close up… what my copy of page 43 looks like, today:

Underneath my breathless journey of scribbled mathematical discovery, this page has a simple lattice representing a 5 x 9 block of the infinite fabric of pitches, illustrating how they are mathematically related (via simple ratios). If the music itself is the picture, lattices like this one are their mathematical underpinning — the picture’s edge.

What was so exciting to me was that it visualizes these relationships in a way that actually explains the science of how we perceive them. It’s elegant, and contains endless patterns to discover.

On showing them page 43, my friends smile politely with just the slightest air of concern: “wow, that’s great. Are you okay?” Each time, I say something like "but… look at how deep this simple diagram goes, how much thought and exploration it pulled out of me, how infinitely interesting it is! Can you believe they never taught this to us in music school!?"

The Proud Autodidact

Grayson Haver Currin, the author of this story (edit: who apparently forgot to mention the name of the Primer’s author, David B. Doty), is writing about a musical concept and a person, yes. But to me the broader topic and star of the show is the experience of teaching yourself. Pitre never went to music school. I went to a lot of music school, but one thing we have in common: neither of us were ever formally introduced to just intonation (if you’d like an introduction yourself, I recently had it on the program for an interview).

We both found it on our own, and explored it on our own. Thus, we each experienced the joy of making a meaningful discovery that was not prescribed by formal education.

Currin labels Pitre a "proud autodidact." At the time I read the article, I had never heard this word, and I admit I didn't bother to look it up. More recently I heard it again — a very close friend offered some encouragement after I was rejected from a very exclusive major university’s PhD composition program. "It's ok, you're happier as an autodidact anyway," he said.

That's a compliment, right? This time I did look it up. And looking it up is, I learned, apparently exactly what an autodidact would do!

"A self-taught person."

To learn one bit at a time, stopping to run endless little experiments. Do I understand this? Can I reproduce it? Can I predict what will happen next? Can I make art with this? What's the next step for me? What other materials are out there waiting to be discovered? What other book, paper, person, or body of work can I unearth? What does my own syllabus look like?

And as a lover of creating my own curriculum, The Just Intonation Primer was my starting block, and is still my north star.

Ancient New Music

Despite how it felt, I wouldn’t dream of claiming I discovered anything new. Many other composers and theorists have been working with just intonation for a very long time. You could probably make an argument that it was Harry Partch who at least "re-discovered" it in the early twentieth century, the way an archaeologist discovers what’s buried for centuries beneath modern civilization.

Partch was the quintessential autodidact. His “primer” was Hermann Helmholtz’s On the Sensation of Tone, and as a music student he was so frustrated with his teachers’ refusal to accept it that he dropped out to follow his own path (one that also included burning his former scores in a potbelly stove, dating Ramon Novarro, and living a “wanderer” lifestyle for nine years during the great depression).

Eventually, through years of exploration and building his own instruments, he created a singular body of work, brought just intonation back from the dead, and inspired an entire generation of musical thinkers (the author of The Primer included).

But just intonation itself is ancient. In fact, our ancestors wouldn't have called it “just intonation” at all: the term is a mid-nineteenth century invention.

Our ancestors would have simply called it "intonation."

The Primer has three main parts:

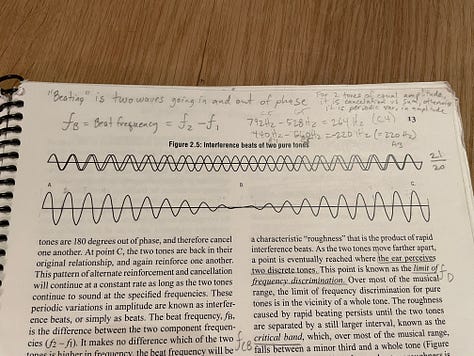

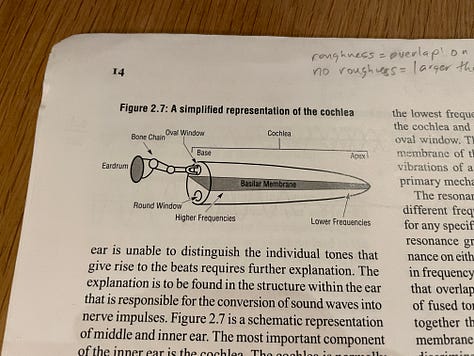

1) An introduction to tone and the physiological basis of how we perceive it.

It offers a simple overview of the way the human ear translates sound vibrations into the sensation of tone, and explains the acoustic and mathematical nature of those vibrations. It explains simple and complex tones, intervals, the harmonic series, phasing and beating, etc.

Particularly mind-blowing for me is the idea of "special relationships," — mathematical intervals between tones that can be recognized easily by any human being from any cultural background, whether trained in music or not.

Given two continuously sounding tones and a knob to control the pitch of the higher one, anyone could easily and intuitively find the exact spot that creates one of the various “special relationships” between their frequencies.

For example, if I give you one tone, you can show me when the second tone is vibrating at exactly a 3:2, 4:3, or 5:4 ratio to the first.

To show me a tempered "perfect fifth," "perfect fourth," or "major third" (the kind taught by modern music theory) would require musical “ear training” and cultural context. And even trained musicians can't do it with exact precision.1

2) An exploration of musical resources.

Once the reader understands the simple math behind the relationship between tones, an exploration of all the possible combinations that could be resources for music-making naturally follows.

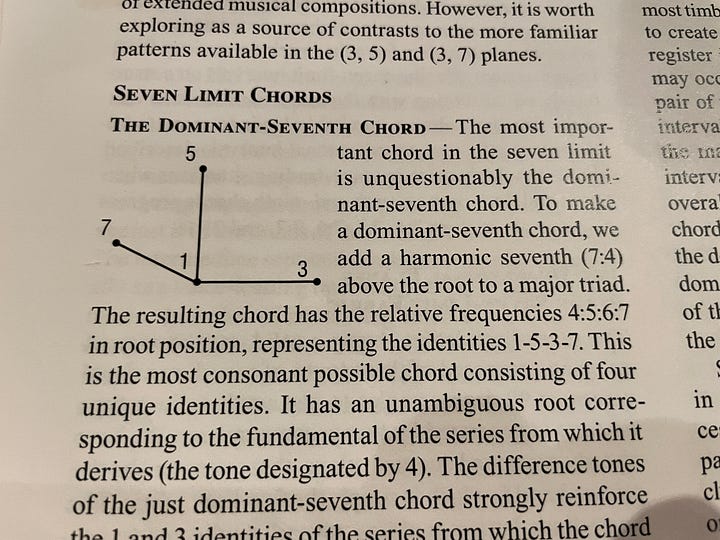

A simple organizing principal inherent in this exploration is that each successive prime number opens up a new dimension of available possibilities. And thus, The Primer moves through the "ladder" of primes, demonstrating the ever-expanding musical resources available within each.

This is where the reader discovers the real basis of familiar concepts musicians take for granted (what is a major triad, really? How did we arrive at a seven- or twelve-note "scale?" What's the difference between Gb and F#?), as well as concepts that will likely be completely unfamiliar even to trained musicians — commas, lattices, prime limits, visualization of pitch relationships in multi-dimensional coordinate space, etc.

What excited me so much about these discoveries is that they aren't theoretically squeezed out of music that already exists. They stand alone. They are math, they are science, they are physiology and psychoacoustics. They are practical musical resources that can be mixed and matched like paint on a composer’s palate.

3) Practical applications of just intonation on acoustic instruments

A practice for using just intonation on acoustic instruments was of crucial importance as recently as twenty years ago, when the latest edition of The Primer was released. At that time music technology offered some ways to break free from equal temperament using computers, but they were typically laborious and required technical knowledge with software or programming. In recent years huge leaps have been made in music tech, so today working with just intonation doesn't require the commitment to instrument-building or extended techniques that it did for generations past.

That said, most composers will still want to work with real acoustic instruments, and this section covers ways to approach doing so despite the fact that modern instruments are all manufactured to play music in equal temperament. It addresses the unique challenges of each instrument family, and strategies for working with performers who may have widely varying levels of knowledge about (or openness to) just intonation.

Multiple Discovery — the Joy (the Agony)

Back to the Times article, and that feeling. Jealousy? Maybe. I've heard it said that jealousy is informative… it educates you on what you subconsciously aspire to be doing. Maybe the jealousy was just telling me something useful, that I was on exactly the right path… for me. I guess I did envy the attention — that's natural. Teaching myself was as lonely as it was wonderful.

But ultimately I was grateful to see this piece help get the ideas get out there, and excited to imagine it might reveal (to a new generation of musicians) the edge of the canvas.

Subscribe for free:

Am I claiming that a trained musician can't tune a tempered perfect fifth precisely? Yes I am… because it's impossible. The ratio of a tempered interval is an irrational number. To try to tune it perfectly would be like trying to calculate all the digits of pi — you can tune it more and more accurately to infinity and never arrive on the exact value.

The Primer is now available in the US from Ingram Spark:

https://shop.ingramspark.com/b/084?params=iisFE1pGpAE68I1cdPeDAmL1gjKjByII2qDPUiuY05G

It is also available from Amazon in most countries.

An ebook version is coming soon.