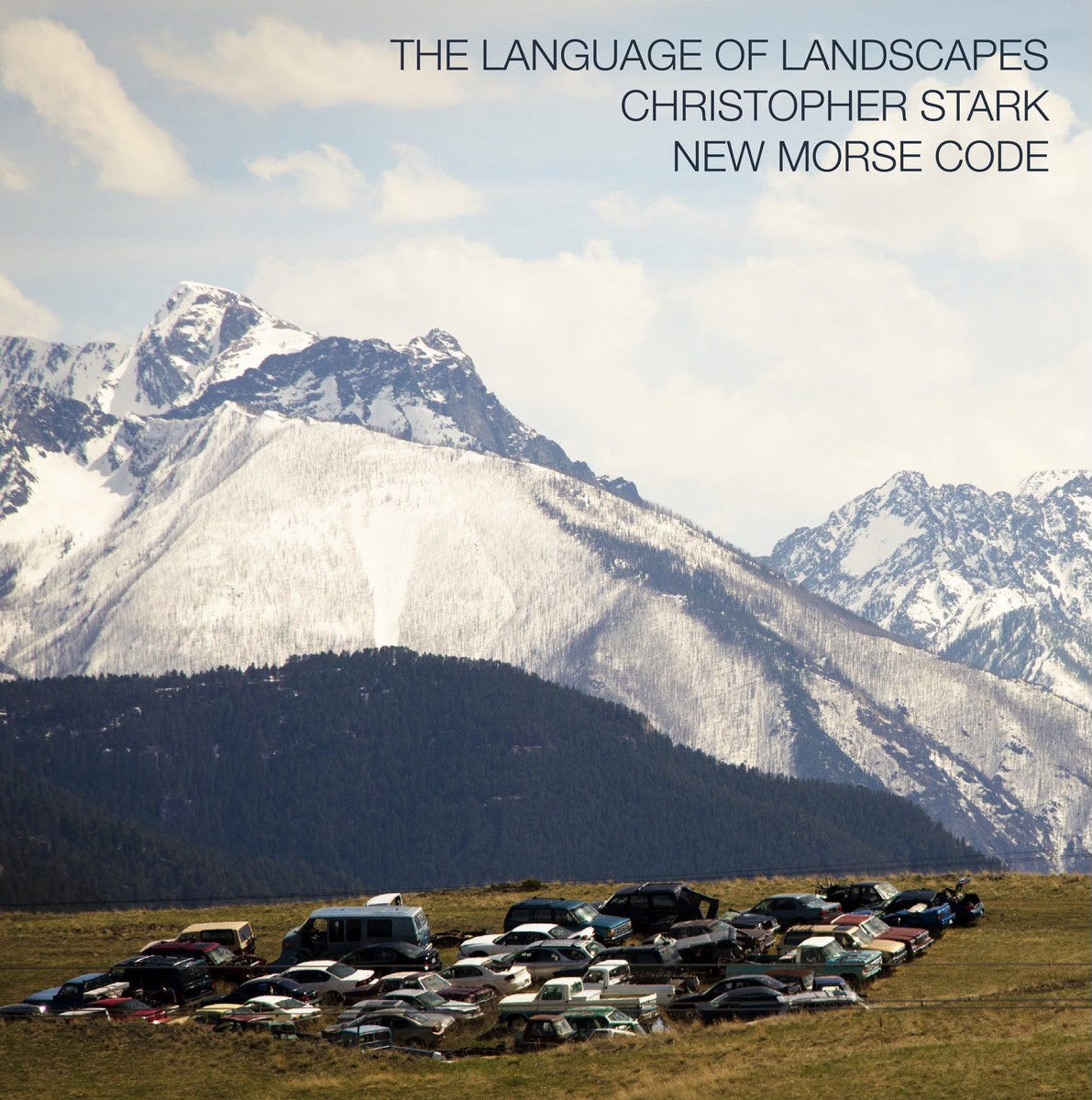

💥 New release this week! I contributed a remix to Chris Stark’s new album The Language of Landscapes. 💥

My track is available now (above, and on bandcamp). If you pre-order the digital or vinyl via its bandcamp page, you get the full album when released on November 22nd.

The Language of Landscapes

Chris Stark, 2024

Performed by New Morse Code

with remixes by Chris P. Thompson, Mvstermind, CNDSD, and Adult Fur.

Really enjoyed this project. I hope you like it.

For me, making remixes is a pure creative joy — like being given access to the hidden inner workings of a piece of music and the mind that created it (and being trusted to mold it with my own ideas).

A Solitary Collaboration

Am I maybe fairly alone on this? The remix can be seen as a way to pay the bills1, or as a promo strategy: help a record cross over into a different market by leveraging an artist of a different genre. Either way, these imply a side project… an afterthought.

But remixing takes on a different flavor when seen as a unique type of collaboration. It’s like having another artist there in the room with me while I create, handing me ideas. And while a remix project is almost always open-ended enough to feel like complete artistic freedom, it also comes with the possibility of useful built-in limitations: a set of materials that can be adopted to whatever degree is useful.

I often find in-person creative collaboration awkward — but that doesn’t mean I don’t yearn for connection. Remixing is a chance to both hear and be heard by another artist I respect and trust, while still remaining within the solitary process that is most effective for me.

🔉👋 Hey, I’m Chris. I write music, and play percussion in contemporary chamber-band Alarm Will Sound. My weekly newsletter Music and Math and Feelings explores a broad range of musical topics: from just intonation to electronic music to drum corps to artist mental health.

You can subscribe for free: new things arrive Sunday mornings.

The Process

If you know what “mixing” is, then you might be confused by the term “remixing,” which doesn’t actually mean redoing the mix, despite… saying exactly that? 🤷♂️

Rather, to remix is to create an interpolation: a new piece of music, using elements of the original.

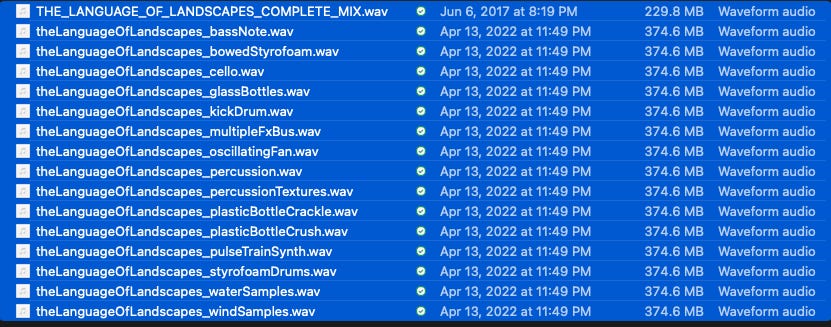

Sometimes the remixer just uses the master recording, essentially approaching it like a giant sample. But more often a remixer receives a folder of “stems” — the individual tracks of a recording, broken apart into separate audio files.

If you drag these files into a digital audio workstation software it instantly recreates the entire recording on a timeline. Now I can mute or solo any track and explore the elements of the music individually.

For example, what are these “_styrofoamDrums.wav” in that list above?

They are beautiful sounds, is what they are.2

EDIT - November 12th: I have received the intel on these instruments! Even as a percussionist, I was stumped, and assumed they were “found” — probably at The Home Depot.

From percussionist Michael Compitello:

That sound is three Styrofoam bowls that Chris and I got at a Michael’s arts and craft store a while back. I have the mounted on a cymbal stand and playing them with the back of a vibraphone mallet.

A couple photos:

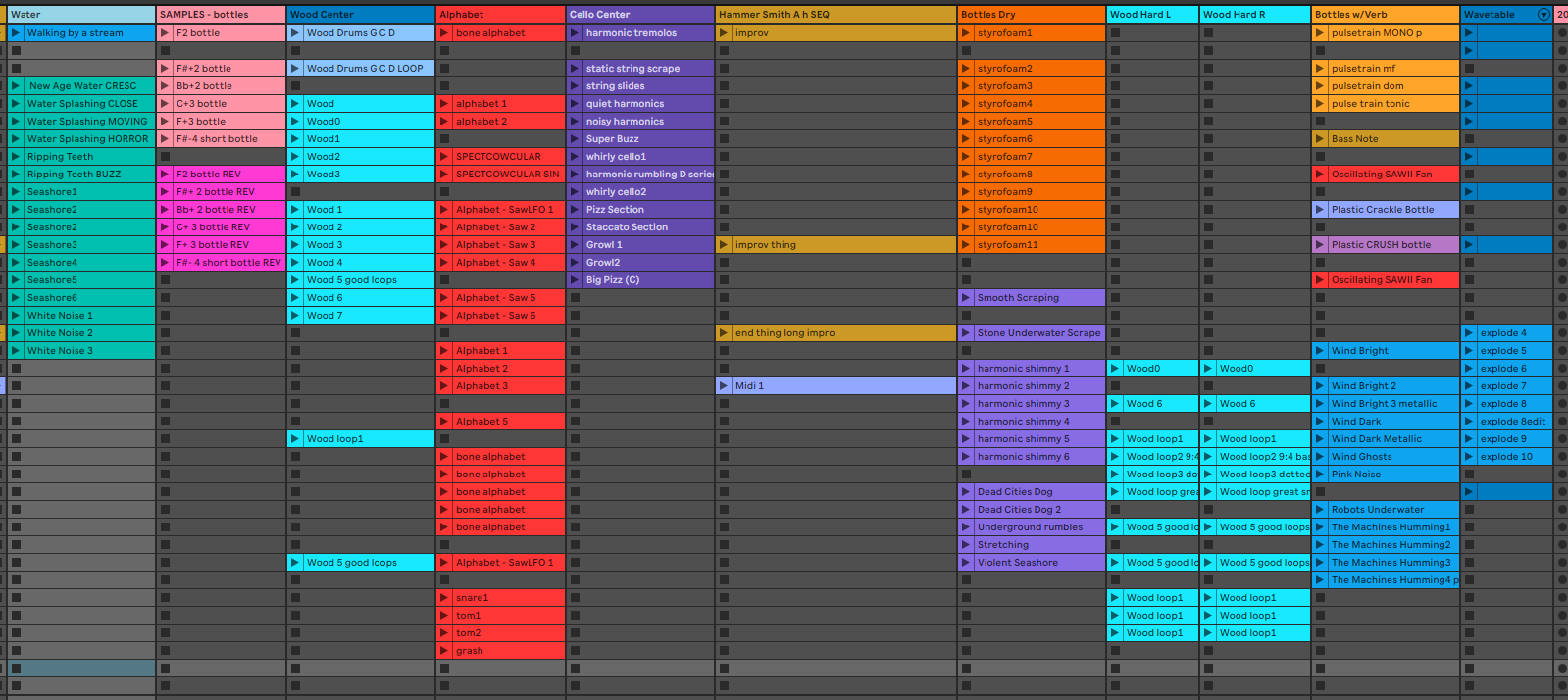

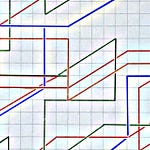

This is where I go to work creatively, like a child with a box of crayons. The software I use has a workspace where clips can be created and organized like post-it notes on a wall. Free from a fixed timeline, they just loop internally, making it really easy to try out endless combinations of sounds and experiment with every manner of manipulation.

One metaphor for this would be like mixing paints on an artist’s palette. This is what my palette looked like at the point I started actually assembling the composition:

The Transformations

I really took that “_styrofoamDrum.wav” stem for a ride.

Before I did anything with it in the computer, I introduced it to what is still the only piece of hardware music production gear I own: my OP-13

Isn’t it beautiful? It’s built to feel more like an extremely well-designed toy than instrument, but don’t be fooled: the audio it produces is super professional quality, and the creative tools are mind-expanding.

Searching through the “_styrofoamDrum.wav” stem, I found the most interesting little bits: a beat hear, a bar there, and loaded them into the OP-1.

Here’s one of the experiments I ran — to “rubber band” the speed of the sample:

Sweet.

One deeply serious pro audio production tool I worked with: the CWO.

This is the CWO:

A full introduction to the earth-shattering genius that is the CWO is too big a topic for today. Shall we just have a listen?

Positively microbial.

These clips are just two of dozens of improvisations I did to generate material with the fourteen stems I was given to work with.

As for that “_styrofoamDrum.wav” sample: after the OP-1 manipulated files were loaded back into the computer, I tempo-synced, layered, phased, and subjected them to other magic like that. Here’s the end result🪄:

The Investigations

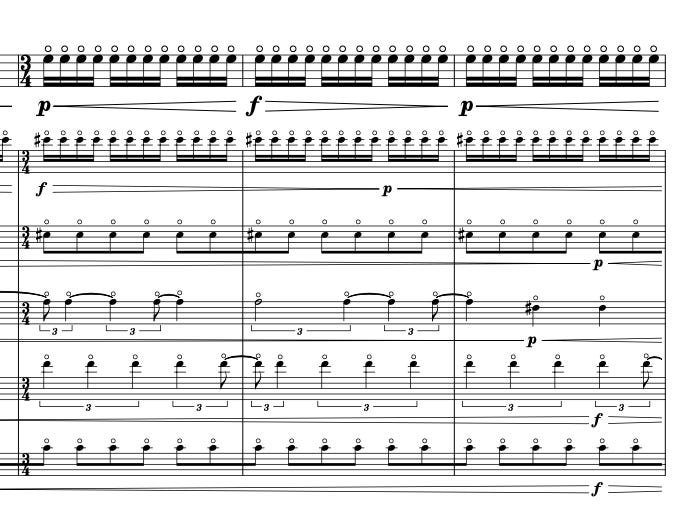

In the case of Language of Landscapes, orienting myself to the original work was made especially easy because I was also given a score. ✨🥹

This gave me instant access to information about every sound, and a big-picture view of the whole piece: what are the pitch and rhythmic material? The tempos? How is the piece structured? How strict was the intention of the notation… was any of it improvised?

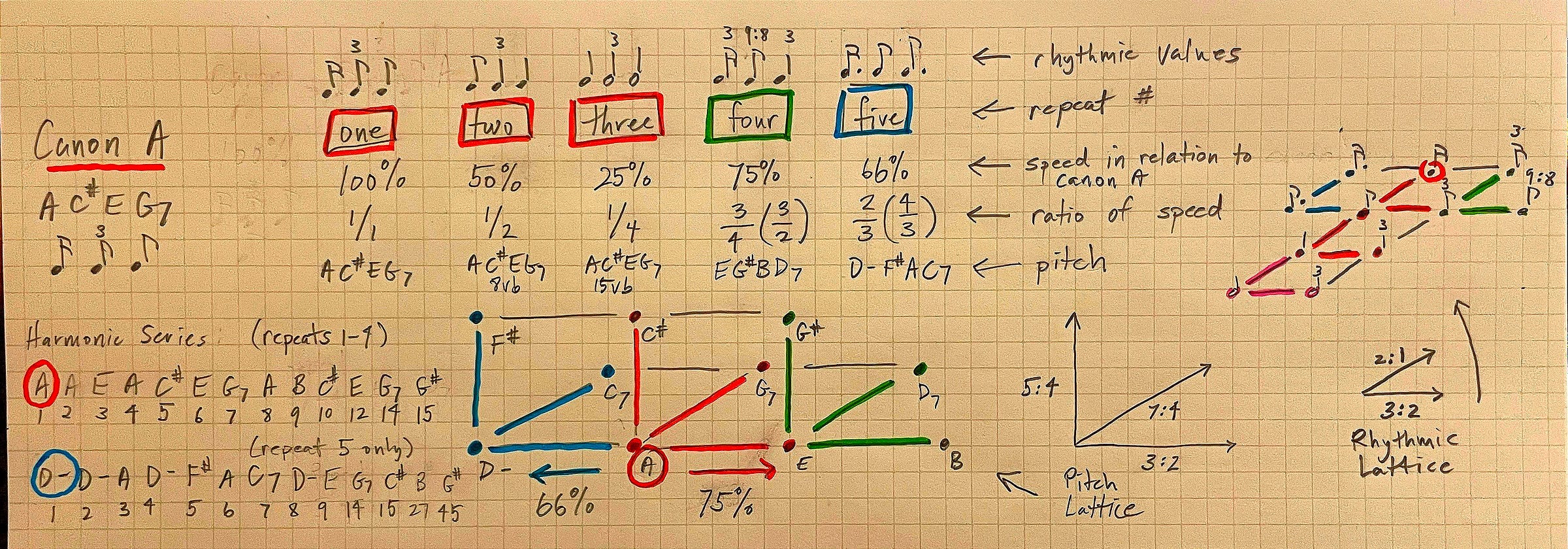

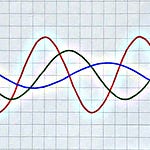

What I suspected about this piece from listening, but confirmed immediately via the score was that The Language of Landscapes is a fascinating exploration of the harmonic series. I knew immediately that I would want to engage with this. But first, a little analysis… because this is fun for me:

😄 Don’t run away. I think I can tl;dr this.

The Language of Landscapes opens with the cellist building a portion of the harmonic series from the top-down, using a live looping mechanism. She performs about 20 seconds worth of music, which is recorded live.

That first “canon” is then played back five times: at 100%, 50%, 25%, 75%, and 66% speeds. Each repetition adds a new layer below the rest: that much lower… and that much slower.

This is an extraordinary compositional and structural idea, and the effect is wonderful. Each time-stretched repetition of the original material becomes a different harmonic partial: not just on the scale of pitch, but on the scale of rhythm/tempo as well.4

With access to his score, I discovered that Chris actually notated out the entire cloud of material that builds up (even though not strictly necessary for practical purposes of performance). Not only did this help make it easy to analyze, but it was a nice moment for me to realize that this willingness to put extra (slightly obsessive?) work into a score to see everything realized on paper — is something we have in common!

An Original Element

A remixer can choose to use as much or as little of the original materials as desired — meaning it’s always possible to add original elements.5

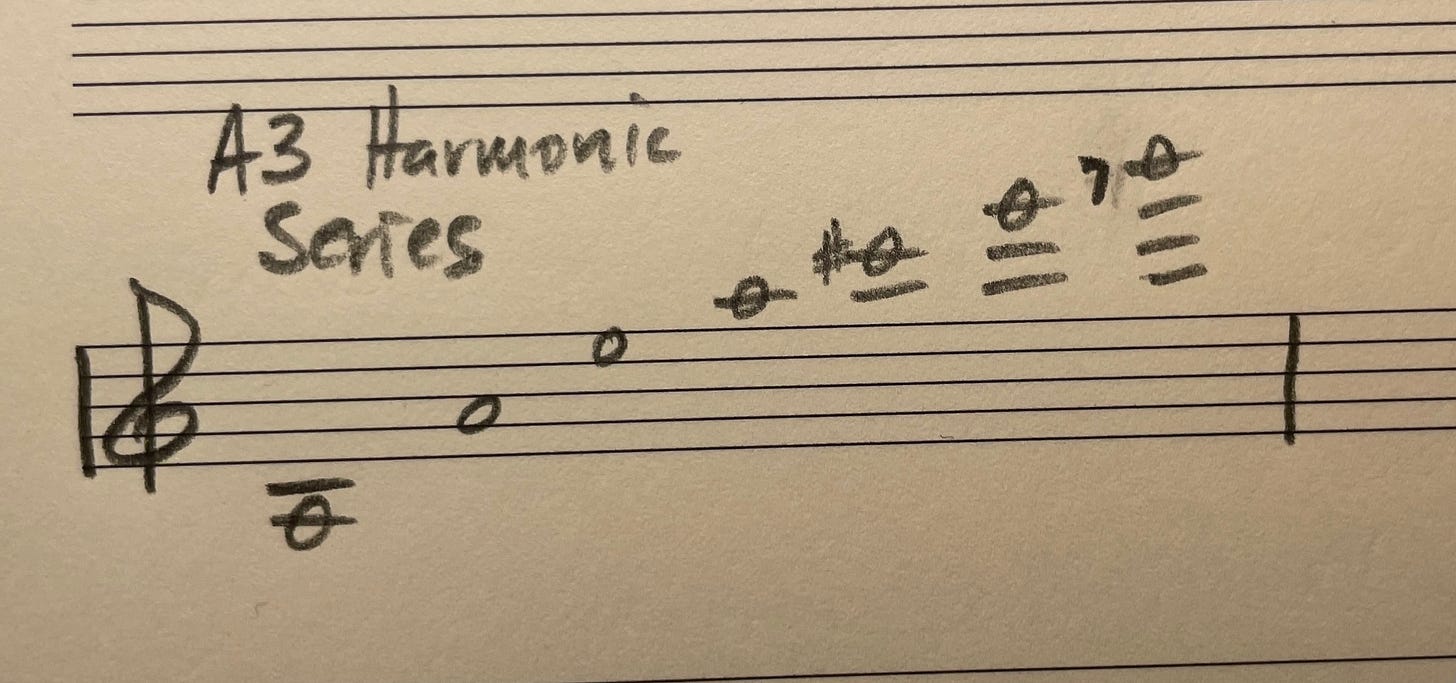

In my case, once I understood what was happening harmonically, I created a piano instrument retuned to the notes of the primary harmonic series (the one with a fundamental of A3, 220 Hz).

My original voice in the remix became this piano, on which I composed new music that used the cloud of cello harmony as its harmonization. Here’s a little demo of the piano tuning, blended with part of the cello stem:

The Backstory

Chris Stark and I met in 2015 at Alarm Will Sound’s Mizzou International Composer’s Festival. I loved his percussion writing and his paradoxical use of electronics in his orchestration to express ideas about nature and natural landscapes.

My percussion part for his piece on the festival included “synthesizer.” Going into the first rehearsal, imagining some kind of boring giant midi keyboard situation, I was absolutely stoked when he introduced himself and handed me this:

Chris built this device and I got to play it. I loved it so much that I sampled it.

Here’s what it sounds like:

And this is how I eventually used it:

Incidentally, this excerpt is also from a remix! Hanabi 「in-ear extended mix」 is me remixing my own earlier track of the same name (remixing my own music is yet another semi-maladaptive habit I learned from Aphex Twin. It is part of what makes his catalogue so truly dizzying).

And in a final twist, Miles Brown and I arranged Hanabi 「in-ear extended mix」 for Alarm Will Sound. We premiered this version at Carnegie Hall in March, and it the studio recording will be out next year. Everything is cyclical! Maybe I’ll remix that recording! A remix of an arrangement of a remix! 😵💫

I made a demo. 😄 Listen here!

Thanks so much for watching/listening. You can subscribe for free:

Get Music and Math and Feelings on Sunday mornings:

If you upgrade to a paid subscription I’ll mail you a vinyl record or compact disc of your choice from my catalog.

Look no further than Aphex Twin’s 26 Mixes for Cash for an example of an artist being tongue-in-cheek about the financial motivation for remixing projects. He has also been fairly snarky about the artists he’s remixing, claiming that he prefers working on something he thinks is bad than good (mean!), or that sometimes he’s considered just having friends do them for him. There’s even an unconfirmed story that he forgot about a remix he had agreed to do until the courier actually showed up at his door to collect it — and so he just handed off something unrelated that he had laying around (and got paid).

Credit to Michael Compitello, percussionist and member of the duo New Morse Code with cellist Hannah Collins. Michael and Hannah performed all the live instruments on the original recording and it was beautiful getting so close to their sounds during the process of remixing.

Just for an idea of how important my OP-1 is to me: nearly every sound you hear on my latest album Stay the Same (that isn’t a piano) either originated or passed through this box!

A C# played back at 75% becomes a G#, and at 66% it becomes an F#. Meanwhile, a sixteenth note played back at 75% becomes a triplet, and at 66% it becomes a dotted sixteenth. This is one of the best real-world examples of my belief that relationships of pitch, rhythm, and tempo can actually be measured, analyzed, and understood on the same terms. I was so excited to uncover this through studying Chris’ score.

The most straightforward example of this would be in a club remix — put an epic “four on the floor” kick drum underneath a Madonna track, and you’ve got something to dance to. That kick sound is entirely the product of the remixer — a completely new and original element.

Share this post