Ticker

A universal point of reference.

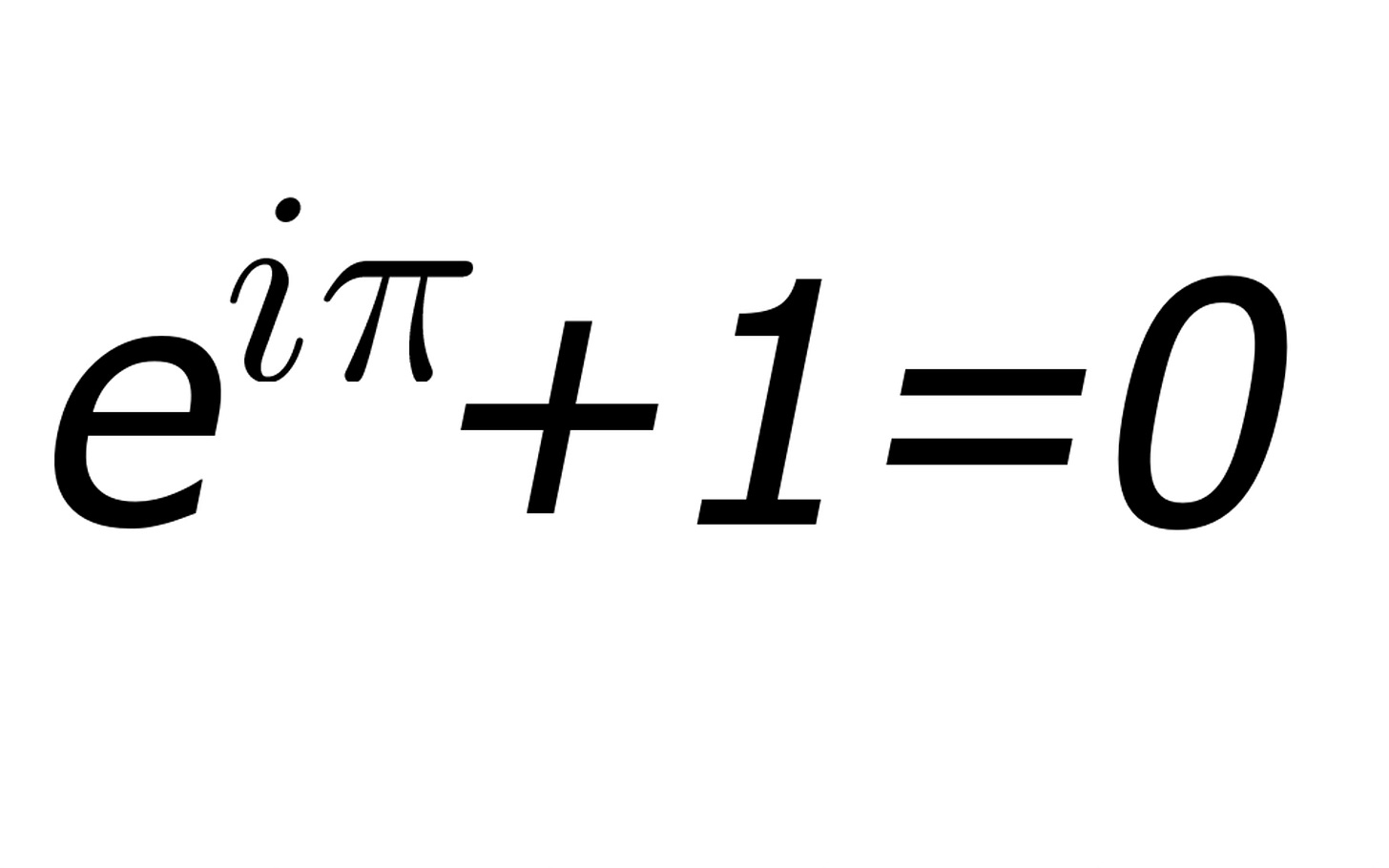

Math and science put immense value on elegance. An elegant concept is succinct, self-contained, aesthetically pleasing, and looks like universal truth using universal points of reference:

My pandemic-era project was to re-learn math from the beginning. I brag about this and people politely smile. I wasn’t expecting to get very far, but that pandemic just kept dragging on. I made it all the way through first-year college calculus! That’s further than I had made it the first time around, in actual college.

Typically, the emotional pull to go all the way back to the beginning is a trap for me… it’s an attempt to be in complete control of my understanding at every stage of learning. This is usually antithetical to actual effective learning. But something felt different about this endeavor. The progression of math doesn’t just go from simple to complex — there are beginnings scattered all over. And the equation above has five of them. Zero: literal emptiness. One: the basis for ℕ the Natural Number System. The constants 𝑒 and π: the basis of logarithms, geometry, and trigonometry. And i: the unit that defines the complex number system: the darkroom of math.

By the time I got to Calculus I had heard various mathematical concepts described as “elegant” but nothing prepared me for the day I followed along with the process of deriving that equation. The starting point was complex but it gradually got simpler and simpler until… there it was: mathematical elegance. It was like the big bang happening in reverse. God-level stuff.

The elegance of Euler’s Identity is the simplicity with which it ties together 5 separate universal frames of reference. Five separate beginnings to five separate systems of thought, merged. Five! In one equation!

In the language of music, tying together five universal reference points would be miraculous. I’d happily settle for three. Okay one! I’ll take one, one is fine!

So you want to play the piano?

I get it — the Alfred Music Publishing Company knows that when you first sit down to learn piano, you’re probably not interested in the universal starting points of music, or the physics of the piano strings. You don’t want to start at the beginning, you just want to be able to play Imagine as soon as possible. So you get:

A diagram of the 7 “notes” (The ABCs!) mapped, inexplicably, to the “white keys.”

A map to “middle C.” Have you ever noticed that “middle C” is not actually the middle of the piano, the middle of that 7 note group, or the middle of… anything? “D” is way more “middle” than “C" (and probably seething with resentment).

A brief refresher on how to count to 4.

Your first song: Hot Cross Buns. (3 notes, right hand only)

If you somehow survive all that without throwing in the towel and going back to Candy Crush, you’re probably rewarded with Ode to Joy (5 notes! Still right hand only).

But in getting started as fast as possible with making music, what have you missed? Will you ever go back to this point and hit rewind to the actual beginning? No matter how beginner or advanced, every single musician and every single person who enjoys music can benefit from understanding more about how we got to those keys and those letters, which (spoiler alert) are not elementary math. From a mile-high view of music and sound, they look more like “bloat” in some centuries-old musical software.

Start on a slower scale than “notes.”

Previously I wrote about my confusion and frustration with the “lesson one”s of musical education. “Day 1” of college-level remedial ultra-basic music theory was similarly baffling to me: diving right into scales and chords, we were taught the concept of the “tonic”: a chord, made up of three notes, which was somehow supposed to “feel like home.”

Stop. Can someone explain to me what a “note” is? A button you press on the piano? A clarinet fingering? The “na” in “Macarena”?

If I could rewind the tape, I’d go back earlier than the point where we start thinking in terms of “notes” (or “pitches,” as I would prefer to introduce them). Understanding pitch is about sensing extremely fast vibrations and measuring tiny lengths of time. It’s about sensations we are able to intuitively experience but that are very hard to actually conceptualize. They are too small… and they move too fast.

I’d start slower: figuratively and literally slower. I would start with the the scale that is larger, and countable — beats. In the sense that beats are individually distinguishable, the scale of “beats” is a far simpler starting point than the scale of “pitch.” Both have ranges with high and low boundaries, as they are perceived differently and independently of one another. But the scale of beats is slower, countable — a more digestible entry point.

Just one more quick glance back to those beginner method books — if you ever used one, do you remember that obligatory page or two on “beats” (and “rhythm” and “time signatures”)? You probably were served up something like this:

Ready, set… “one.”

🤷♂️🤷♀️

Next, it might suggest that you:

Tap your foot to the “quarter” note.

Four of those taps makes a “whole” note.

NO HOLD UP.

Wouldn’t it make more sense if ONE foot tap was a “whole note?” Why is a whole foot tap only a quarter “note”? How fast am I supposed to be counting? Why count fractions, America? Brits call it a “crotchet”… at least that sounds like a “whole” thing? Add up four of those crotchets and you get… a semibreve. Oh no… “semi” is another fraction, and “breve” means “double whole note.” So “half a double whole note??”

Got it. Four foot tap crotchets equals “half a single double-whole!” Not. Elegant.

Yes, I’m being deliberately obtuse for comedic effect. Seriously though, with all joking aside: how does all this relate… to a human being?

Right, foot taps. But is foot tapping (or hand clapping, or the sound of a faucet dripping, or the tempo of Hey Ya! or the bass drum in Stars and Stripes Forever) really the broadest possible reference point? If we really want an internal human reference point for the scale of countable time that can apply to the music of every culture and every human being, isn’t there a reference point they all actually share?

🙅🏻♂️ Warning: what I’m about to say is not about feelings. This is not a sentimental catchphrase, or the tagline to a Hollywood drama about a drummer who triumphs over adversity. This is coldly clinical. It’s about physiology, and physiology only.

I hope you trust me? Promise you won’t bolt. Here it is:

The universal reference point for understanding countable time in music is the human heartbeat.

I SAW THAT EYEROLL. Please, please stay with me here. This is not about emotion — it’s about a hunk of weird muscly tubes contracting and relaxing to spit blood through veins.🫀 The heart is simply a universal human reference point for making meaning from a certain scale of lengths of time — specifically, periodic lengths of time on the scale that is countable.

Every human on earth has one, and if you’re alive, it’s working. You have no choice. You can’t actually be “heartless” and your heart certainly can’t “break.” You’d die. The biological functioning of the heart is a beginning: a universal shared experience. And as human beings, its range of rates is one of a small handful of universal shared experiences that directly applies to a range of rates in music (another is that we all breathe… and a third is that we evolved to communicate with vocal cords. Thes are perceived on slower and faster scales that the heart rate, respectively, more on those later). But if you need an elegant beginning for understanding a planet full of wildly different music and human reactions to countable tempo, the heartbeat (and it’s measurement: the heart rate), is it.

Onto some music, apologies for taking so long to get here. The excerpt for today:

Marking Time.

If you know me personally or have ever heard me talk about music in any context, you already know this: I love metronomes. The tick of a metronome organizes time into a grid I can understand and feel. It stops musical arguments dead. It draws a floor under my feet so I can dance. What a beautiful machine. It should have an emoji.

I wrote Marking Time in 2021 for the Utari Duo: Haruka and Rika Fujii. Central to its construction is the use of a sampled metronome, which I’ve manipulated in all sorts of ways. In starting the piece, I thought it would be cool to use the various ticks of metronome as part of the instrumentation of the composition (whereas typically, the function of a metronome is to support performers in practice and rehearsal, and then be removed for performance). My starting point was just this simple idea: it wouldn’t disappear before the concert, but remain — as an equal voice in the ensemble.

But through the process of composing the piece, I made a somewhat obvious but still irresistible connection: in retuning the tick of the metronome down into the bass range, it morphed into a sort of kick drum, and then… a heartbeat.

I thought of the long days of rehearsal when I was a performer in a drum & bugle corps as a teenager. The brutal physical activity of the show and the intense cardiovascular endurance it required. The relentless schedule of 10 hour rehearsals, 7 days a week. The anxiety and pressure of performance. The tick of a crudely amplified metronome behind us… and my constant hope for the sudden summer downpour that would send us into the gym for some “down time” (and a lowered heart rate) on a sleeping bag… with the sound of the rain pounding the asphalt outside, and the comforting aroma of the newly wet ground.

The story my brain was trying to tell (and the fuel for the dramatic arc of the piece) became clear: an external reference point (the tick of the metronome) becomes internalized, step-by-step, until it is perceived as the universal reference point (the beat of the heart rate).

⏱️ Ticker

The function of the metronome is to demonstrate countable lengths of periodic time with mathematical precision, using a defined scale. No, adagio, you’re overly vague, I don’t speak Italian, and you’re not invited to this party. We speak science here. After all, we put in so much work throughout human history observing the cycles of seasons, moons, day/night, and their effect on human beings. We then managed to translate them into an elegant system of interrelated scales: years, months, days, hours, minutes, and seconds… if we want to measure the scale of countable time in music, why not just stick with those? Out comes the metronome.

You probably already know that the scale on a metronome is the number of beats in the course of one minute. Beats Per Minute. I like to call them “Bs Per M,” but convention demands we abbreviate as BPM.

By the definition of one second, there are 60 seconds in a minute. So, now and forever, seconds are always ticking away at 60 BPM.

You know what else is probably ticking at or around 60 BPM? Your heart, right now. 1

Metronomes have a range of rates, their purpose being to categorize what’s musically useful… and that range is measured in BPM. What physical reference point do we have to those rates? What universal shared experience do we have for understanding how periodic cycling rates of time feel? What human function speaks the language of “beats per minute.”

We naturally gravitate to 60 BPM as a starting point when thinking about beats. This is certainly because of its 1:1 relationship to seconds, but I would argue also because of its aforementioned elegance.

Interestingly, around 60 BPM is generally cited as a healthy resting heart rate for average adults. But the relationship between countable time in music and heart rate gets even harder to deny when you compare the full ranges of both:

🫀 Ticker

Before there were clocks or metronomes to to give meaning and context to certain cycles of time, there was that heartbeat. Feeling time on this scale is a central experience for humans. We’re rarely consciously aware of it, but we’re feeling the regular, countable heartbeats every single moment we are alive. No one ever needed to teach us how to interpret the meaning of heart rate: the more we live, the more associations we make with points on the scale:

Sitting? It’s slow. Moving? Faster. Scared? Real fast. Panic? It’s RACING. Are you older? Slower. Younger? faster. Are you an excited infant? (Wheeeeeee! Breaking 200!)

A single heart rate can take on many different possible associations, all exploitable by music. You might have experienced 140 as anticipatory anxiety, or as the aftermath of almost getting hit by a car. Those experiences become possible interpretations of a heart rate.

I’m going to start letting the word tempo slip in here, because of its ubiquity. Look no further than dance music for a direct correlation between the tempo of music and the mechanism of the human heart. 🕺 A well-crafted DJ set is literally managing a range of heart rates: it’s why it categorizes itself using the exact same terms: BPM.

BPM is a real physical sensation that is familiar to everyone, and that’s the reason it’s such an effective scale of measurement in music, with roughly 40 and 200 being the lower and upper limits, respectively.

Just to put them side-by-side:

- A standard metronome has a full range of roughly 40 - 200 BPM.

- The human heart rate also has a full range of roughly 40 - 200 BPM.

This is not a coincidence.

You can measure the whole range of both musical tempo and the human heart rate on the dial of a metronome.

Why did no one tell me this?

This scale is useful, simple, and immediately understandable. The connection is elegant and universal. It makes for a perfect starting point.

Going forward: speeding up and slowing down

Just to foreshadow where this range transitions to in the human body, let’s have a look at the upper and lower limits of that dial:

At the bottom of the metronome’s range, going below approximately 40 BPM, we start to lose the ability to intuitively predict when the next tick will occur. We’re not physically familiar with a heart rate that slow. As the ticks get slower, we need to multiply them to jump back into the countable range: first by 2 or 3, then eventually again to fit 4 or 6 within each tick. As they continue to slow, the cycles of time transition from “ticks” into something resembling “moments.” Time gets more flexible. “Heartbeats” turn into “breaths”… and we’re far more likely to lose count of breaths (see: the practice of meditation). This is a new and different scale, measurable in seconds, and musically more applicable to phrases, form, and structure.

At the top of the metronome’s range, going above approximately 200 BPM, we start to lose the ability to count the ticks individually. We’re not physically familiar with a heart rate that fast. As the ticks get faster, we need to divide them into groups to jump back into the countable range. It’s like a stock splitting: the brain cuts the tempo in half or in thirds, grouping the beats in 2 or 3. As it gets back up to 200 again, maybe we split it into groups of 4 or 6. Maybe we get to groups of 8 before the point where we no longer know exactly what we’re hearing at all: the individual ticks have blurred into each other.

And then all of a sudden that blur becomes… a “note.” We’re now in a new and faster scale, musically applicable to pitch: those heartbeats have moved into our vocal cords, and become our singing voice.

Thanks to Utari Duo: Haruka and Rika Fujii.

You can watch my full music video of the Marking Time premiere, watch a video of me talking a little more about the creation of the piece, and purchase score and parts, at https://www.chrispthompson.com/markingtime

Subscribe for free:

Also, you know what’s ELEGANT? The number 60. Not just because it’s the way we divide hours into minutes and minutes into seconds… but because of its divisibility. There are twelve ways to divide it into equal parts. It’s the smallest number with all the factors 1 through 6. After all, we’re dividing time here. We don’t want weird decimals if we can help it. We want gorgeous and elegant whole numbers.

Remember how I mentioned that those letters taped to the piano keyboard are actually miles ahead of any simple mathematical starting point? Let’s just say that those letters are… not based on elegant whole numbers. Wow, will you be horrified. I’m gonna let mom tell you about that when you’re a little older.

But 60 is awesome. 60 was the “base” used for counting by ancient Sumerians and Babylonians: they were apparently really into dividing things up evenly.

60 is even “the sum of it’s unitary divisors” making it a unitary perfect number, which I don’t understand but which sounds real elegant!

60 is the highest score that can be achieved with a single dart. 🎯